The C++ code that goes with this blog post is at https://github.com/Atrix256/PairwiseVoting/

There is a great video on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSDBbCaO-kc) that explains how voting was implemented in the third Summer of Math Exposition (https://some.3b1b.co/) from 3 Blue 1 Brown (https://www.youtube.com/@3blue1brown).

In the Summer of Math Exposition, people make online math content, and prizes are given to the winners. The challenge is there are thousands of entrants, where a typical entry may be a 30 minute video of nontrivial mathematics. How could all those entries be judged to find the best ones?

The video I linked before talks about how to approach this with graph theory and makes use of a lot of really interesting math, including eigenvectors of adjacency matrices. The result is that they have volunteer judges do a relatively small number of votes between pairs of videos, and from that, the winners emerge in a way that is strongly supported by solid mathematics.

I recommend giving that video a watch, but while the motivation of the technique is fairly complicated, the technique itself ends up being very simple to implement.

I’ll give some simplified background to the algorithm, then talk about how to implement it, and finally show some results.

Background

Let’s assume there are N players in a tournament, where there is an absolute ordering of the players. This is in contrast to rock, paper, scissors, where there is no 1st place, 2nd place, and 3rd place for those three things. We are going to assume that there are no cycles, and the players can actually be ordered from best to worst.

A way to find the ordering of the N players could be to take every possible pair of players A and B and have them play against each other. If we did this, we’d have a fully connected graph of N nodes, and could use an algorithm such as Page Rank (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PageRank) to turn the results of that into an ordered list.

If there are N players, we can use Gauss’ Formula (https://blog.demofox.org/2023/08/21/inverting-gauss-formula/) to calculate that there are N * (N-1) / 2 matches that would need to be played. For 1000 players, that means 499,500 matches. Or in the case of SoME3 videos, that is 499,500 times a volunteer judge declares which is better between two 30 minute math videos. That is a lot of video watching!

Tom Scott has an interesting video about this way of voting: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ALy6e7GbDRQ. In that situation, it was just an A/B vote between concepts like “bees” and “candy”, so was a lot quicker to make pairwise votes.

Wouldn’t it be nicer if we could do a smaller number of votes/matches, and do a sparse number of the total votes, while still getting an as accurate result as possible?

The SoME3 video explains how to do this and why the method works.

One thing the video talks about is the concept of a “radius of a graph”.

If you have a node A and a node B, the shortest path on the graph between those nodes is the distance. If you calculate that distance for all nodes, the largest value you get is the radius of the graph.

It’s also important that there is a path between every node to every other node! This is known as the graph being “connected”. If the graph isn’t connected, the radius is undefined since the largest distance will be infinite (no path between 2 nodes). If the radius is 1, such that there is a connection between each node to every other node, then the graph is called a complete graph.

The video talks about how it is important to make the radius smaller for a higher quality result of the voting. The larger the distance between two nodes, the less direct the comparison is between those two nodes which makes their ordering less certain. The shorter the distance, the more direct the comparison is, which makes their ordering more certain. Reducing the graph radius ensures that all distances are smaller or equal to that radius in distance.

You can imagine that if you were to pick pairs to vote on at random, that it probably isn’t going to be the optimal voting pairs to give the smallest radius of a graph. For instance, due to the nature of uniform random numbers, you might have 20 votes between node 5 and other nodes, while you only have 2 votes between node 4 and other nodes. A node picked at random is more likely to have a shorter path to node 5 than it is to node 4, and so node 4 is going to be the longer distance that defines the overall radius of the graph. If the votes were more evenly spread to all the nodes, the maximum distance (aka radius) would go down more.

The Algorithm

The algorithm ends up being super simple:

- Visit all nodes in a random order. This is a random cycle or a random Hamiltonian cycle.

- Each connection between nodes in that cycle are votes to be done or matches to be played. So for N nodes, there are N votes. Note that each node is involved in 2 votes, but it’s still only N votes!

- That is one iteration. Goto 1 again, but when generating a random cycle, make sure it doesn’t contain any edges (votes) already done in a previous iteration. Repeat until you are satisfied.

A simple way to implement visiting all nodes in a random order is to just shuffle a list of integers that go from 0 to N-1.

The magic is that each iteration decreases the radius exponentially.

So, it’s very simple and effective.

Alternate Algorithm

I spent some time thinking about this algorithm and trying to come up with alternatives.

One thing that bothered me was generating random cycles, but making sure no edges in the cycle were already used. That loop may take a very long time to execute. Wouldn’t it be great if there was some O(1) constant time algorithm to get at least a pseudorandom cycle that only contained edges that weren’t visited yet? Maybe something with format preserving encryption to do constant time shuffling of non overlapping cycles?

Unfortunately, I couldn’t think of a way.

Another thought I had was that it would be nice if there was some way to make a “low discrepancy sequence” that would give a sequence of edges to visit to give the lowest radius, or nearly lowest radius for the number of edges already visited.

I also couldn’t think of a way to do that.

For that second idea, I think you could probably brute force calculate a list like that in advance for a specific number of nodes. Once you did it for 10 node graphs, you’d always have the list.

I didn’t pursue that, but it might be interesting to try some day. I would use the radius as the measurement to see which edge would be best to add next. Before the graph is connected, with a path from every node to every other node, the radius is undefined, but that is easily solved by just having the first N edges be from node i to i+1 to make the graph connected.

In the end, I came up with an algorithm that isn’t great but has some nice properties, like no looping on random outcomes.

- The first iteration makes N connections, connecting each node i to node i+1. This isn’t randomized, but you could shuffle the nodes before this process if you wanted randomized results after this first iteration.

- Each subsequent iteration makes N new connections. It chooses those N connections (graph edges) randomly, by visiting all N*(N-1)/2 edges in a shuffled, random order. It uses format preserving encryption to make a shuffle iterator with random access, instead of actually shuffling any lists. It knows to ignore any connection between nodes that are one index apart, since that is already done in step 1.

The end result is that the algorithm essentially makes a simple loop for the first iteration, and then picks N random graph edges to connect in each other iteration.

An important distinction between my algorithm and the original is that after the first iteration, the links chosen don’t form a cycle. They are just random links, so may involve some nodes more often and others less often, making for uneven node distances, and larger graph radius values.

Because of this, you could call the SoME3 algorithm a “random cycles” algorithm, and mine a “random edges” algorithm.

Once You Have the Graph…

Whichever algorithm you use makes you end up with a connected graph where the edges between vertices represent votes that need to be done (or matches that need to be played).

When you do those matches, you make the connections be directed instead of undirected. You make the loser point to the winner.

You can then do the page rank algorithm, which makes it so rank flows from losers to winners through those connections to get a final score for each node. You can sort these final scores to get a ranking of nodes (players, videos, whatever) that is an approximation of the real ranking of the nodes.

In the code that goes with this post, I gave each node a “random” score (hashing the node id) and that score was used to determine the winner in each edge, by comparing this score between the 2 nodes involved to find which one won.

Since each node has an actual score, I was able to make an actual ranking list to compare to the approximated one.

We now need a way to compare how close the approximated ranking list is, compared to the actual ranking list. This tells us how good our approximation is.

For this, I summed the absolute value of the actual rank of a node minus the approximated rank of a node, for all nodes. If my thinking is correct, this is equivalent to optimal transport and the 1-Wasserstein distance, which seems like the appropriate metric to use here (more info: https://blog.demofox.org/2022/07/27/calculating-the-similarity-of-histograms-or-pdfs-using-the-p-wasserstein-distance/).

I divided this sum by the number of nodes to normalize it a bit, but graphs of different sizes still had slightly different scale scores.

Results

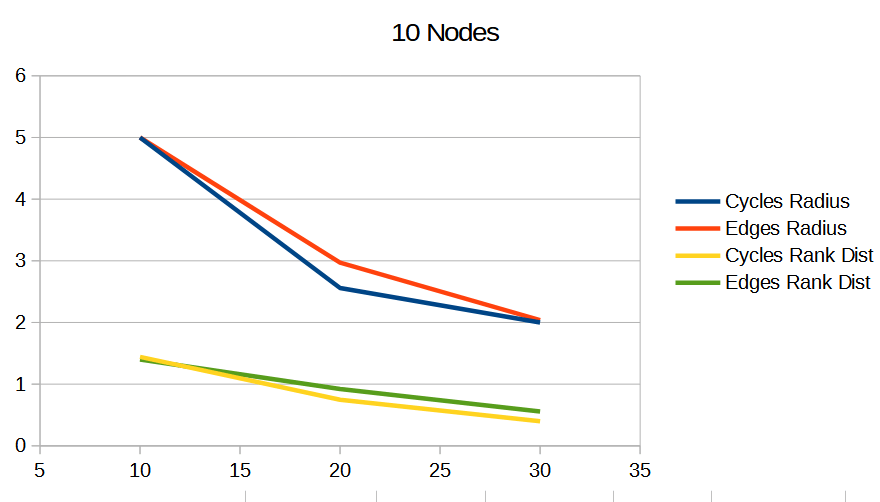

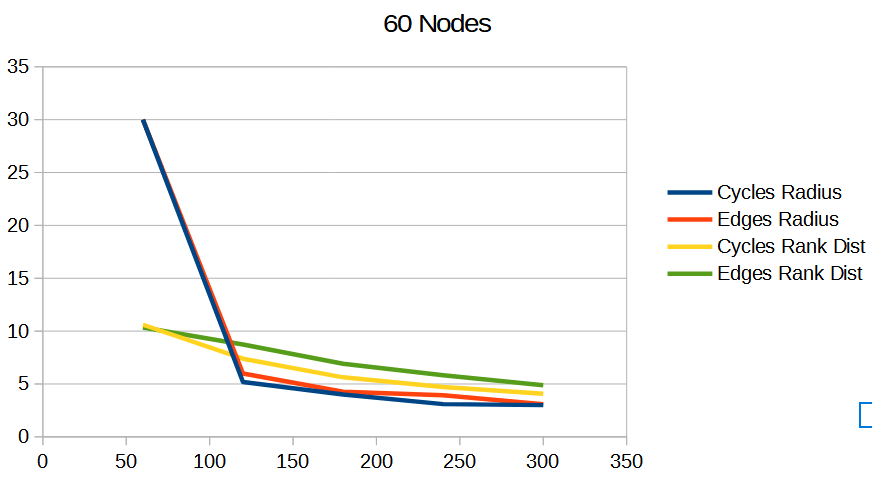

Below are some graphs comparing the random cycles algorithm (“Cycles”) to the random edges algorithm (“Edges”). The radius is the radius of the graph, and lower is better. The rank dist says how accurate the approximated rank was, and lower is better.

The graphs show that the random cycles algorithm does better than the random edges algorithm, both in radius, as well as accuracy of the approximated ranking.

Frankly, each iteration being a random hamiltonian cycle on a graph has a certain “low discrepancy” feel to it, compared to random edge selection which feels a lot more like uniform random sampling. By choosing a random cycle, you are making sure that each node participates in 2 votes or matches each iteration. With random edge selection, you are making no such guarantee for fairness, and that shows up as worse results.

To me, that fairness / “low discrepancy” property is what makes choosing random cycles the superior method.

In the graphs below, the x axis is the number of votes done. Each data point is at an iteration. The graphs show the average of 100 tests.

What About Tournament Brackets?

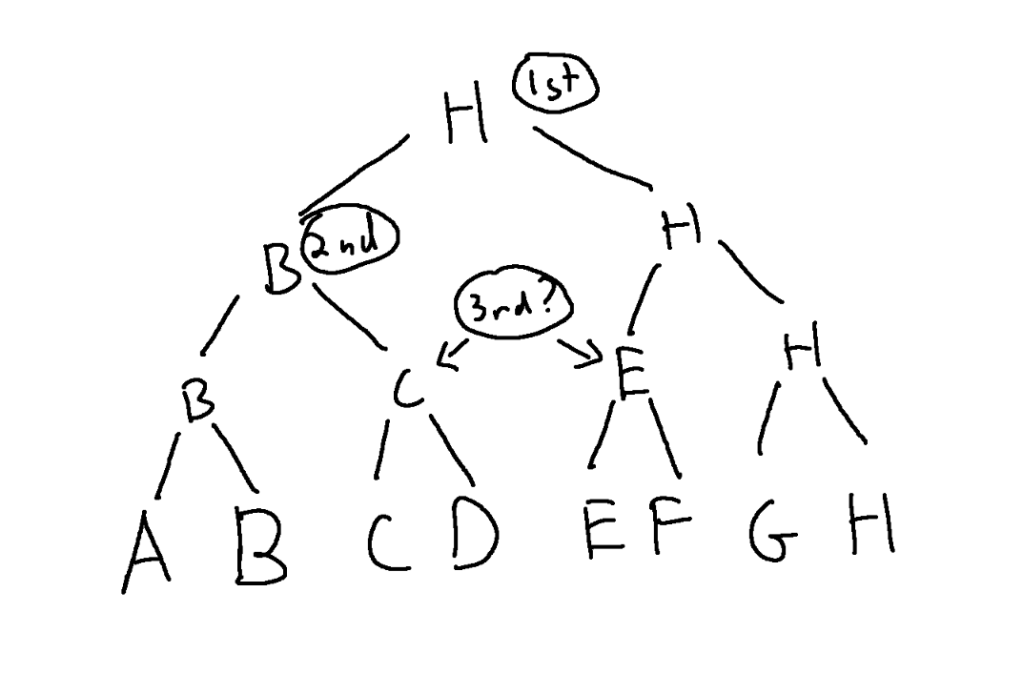

Tournament brackets are another way of finding a winner by having pairwise votes or matches.

If you have 8 players, you pair them up and play 4 matches to get 4 winners. You then pair them up to get 2 matches and 2 winners. Lastly you play the last match to get the winner. That is 4+2+1=7 matches for players.

If you have 16 players, you first do 8 matches, then 4 matches, then 2 matches, then 1 match. That is 8+4+2+1=15 matches for 16 players.

In general, If you have N items, it only takes N-1 votes or matches to get a winner – and assuming matches have no random chance in them, gives you the EXACT winner. In the SoME3 algorithm, each iteration takes N votes or matches, and there are multiple iterations, so seems to take a lot more votes or matches.

That is true, and tournament brackets are very efficient at finding the winner by doing pairwise comparisons.

Tournament brackets can only tell you who is first and who is second though. They can’t tell you who is third. They can tell you who made it to the finals or semi finals etc, but the people who made it to those levels have no ordering within the levels.

Another factor to consider is that who plays in a tournament match depends on who won the previous matches. This makes it so later matches are blocked from happening until earlier matches have happened.

If these things aren’t a problem for your situation, a tournament bracket is pretty efficient with matches and votes! Otherwise, you might reach for the SoME3 algorithm 🙂

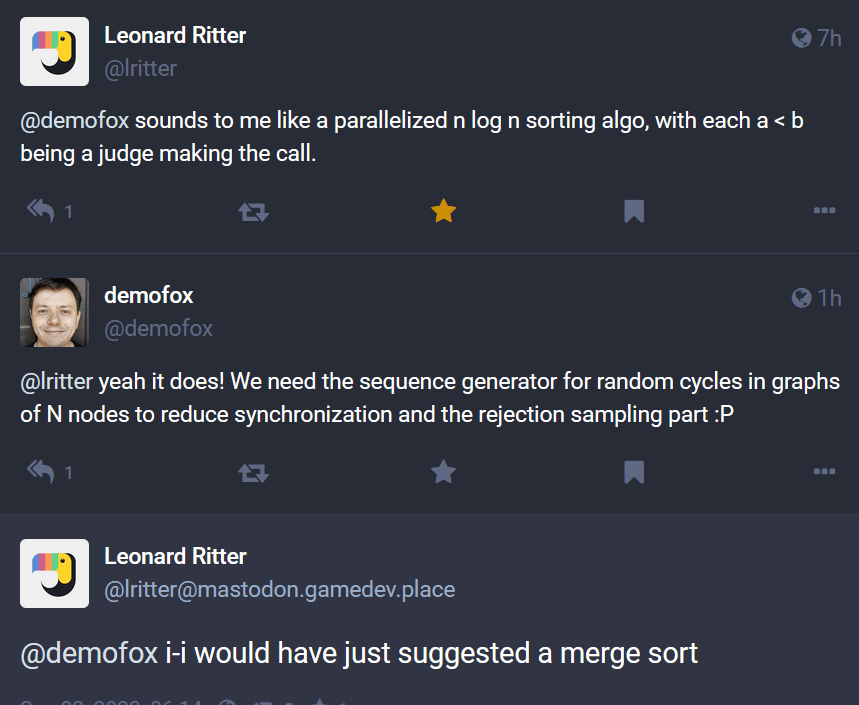

What About Merge Sort?

Leonard Ritter aka paniq (https://mastodon.gamedev.place/@lritter) brought up this excellent point on mastodon.

So interestingly, merge sort is a lot like tournament brackets, where the earlier matches define who plays in the later matches. However, the number of matches played in total can vary!

Lets say you had two groups of four players, where in each group, you knew who was best, 2nd best, 3rd best and last. And say you wanted to merge these two groups into one group of eight, knowing who was best, 2nd best, etc all the way to last.

The merge operation of merge sort (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4VqmGXwpLqc) would do between 4 and 7 comparisons here to get that merged list, which is between 4 and 7 matches or votes for us. If you then wanted to merge two groups of 8, it would do between 8 and 15 comparisons.

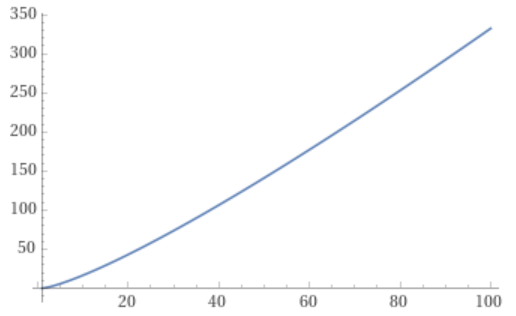

In general, if you have N items, the fewest number of comparisons merge sort will do is N/2 * log2(N). This is each merge will at minimum do N comparisons, and there are log2(N) levels of merging.

The graph for that is pretty linear which is nice. No large growth of comparisons as the number of items or nodes grow. This is what makes merge sort a decent sorting algorithm.

Ultimately, this connection shows that the SoME3 voting algorithm can also be seen as an approximate sorting algorithm, which is neat.

Links

Here are some links I found useful in understanding the Page Rank algorithm:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PageRank

https://www.ccs.neu.edu/home/vip/teach/IRcourse/4_webgraph/notes/Pagerank%20Explained%20Correctly%20with%20Examples.html

https://towardsdatascience.com/pagerank-algorithm-fully-explained-dc794184b4af

Pingback: Generating Hamiltonian Cycles on Graphs with Prime Numbers of Nodes, Without Repeating Edges « The blog at the bottom of the sea