The C++ code that goes with this blog post can be found at https://github.com/Atrix256/GoldenRatioShuffle and includes a header file that contains a shuffler that should be easy to drop into other C++ code.

A shuffle iterator lets you iterate through a shuffle without actually doing the shuffle. It can provide the next item when asked while only storing your current index into the shuffle and the random seed. A friend and I wrote an article showing how to achieve that using mathematics and cryptography: https://www.ea.com/seed/news/constant-time-stateless-shuffling

However, the shuffle made with that technique is a “white noise shuffle”. That is, each item in the shuffle has equal probability of being anywhere in the shuffle and each item in the shuffle an independent random number (uniform random selection without replacement). This is useful anywhere a shuffle is used, but in many situations, the algorithm using the shuffled data could perform better if it could use something better than white noise. I recorded a video that talks about the benefits of going beyond white noise here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tethAU66xaA

In this post, I’ll show how to make a stateless constant time shuffle iterator which:

- Takes an irrational number to drive the shuffle sequence

- Takes a random seed

- Supports random access

- Supports inversion

Each briefly explained:

Takes an irrational number to drive the shuffle sequence

The golden ratio is best, but if you need multiple shuffles, having two shuffles based on the same irrational number will cause them to be correlated. Like imagine two sine waves, but starting at different angles (phases / offsets). That correlation will show up in what you are using the shuffles for and be a problem. Using different high quality irrational numbers for each shuffle will make them be more uncorrelated, depending on the numbers used. See the previously mentioned youtube video for more details about high quality vs low quality irrational numbers. Note that this also touches on something I call “co-irrational numbers” that you can read about here: https://blog.demofox.org/2020/07/26/irrational-numbers/

The golden ratio is the best choice, but the square root of 2 is also good, as is the square root of 3. Pi however is a very bad choice!

Takes a random seed

The shuffle in this article is a deterministic sequence that gives every item [0,N) exactly once before repeating, and does so in a quasirandom order.

You can imagine that you could add a constant to every item in that sequence and apply modulo N to bring it back to being in [0,N). That constant is the random seed and that is how we apply the seed. So, for a list of N items long, the random seed can be any value between 0 and N-1.

Supports Random Access

You can either ask for the next item in the list, or you can ask for the Mth item in the list.

That is, you can have a shuffle with 4 billion items in it and ask “what is the 1 billionth item in the shuffle?” and it will tell you in constant time – taking just as much computing power / time as if you asked what the 1st item in the shuffle was.

Supports Inversion

You can ask when a specific item will show up in the shuffle.

Again, if you are shuffling 4 billion items, you can ask it “At what point in the shuffle does the 5th item appear?” and it will give you the answer, in constant time again.

Let’s dive into the details.

Low Discrepancy Sequence to Low Discrepancy Shuffle

A well known and powerful one dimensional low discrepancy sequence (LDS) is the golden ratio LDS, which is calculated like this in C++:

float GoldenRatioLDS_NextValue(float lastValue)

{

static const float c_goldenRatio = 1.618033988749f;

return std::fmod(lastValue + c_goldenRatio, 1.0f);

}

The first time you call that function, you can pass any value in between 0 and 1 as the “initial state” or “random seed”. Every time you call it after that, it returns a value between 0 and 1 that you can use as a “random number” in your code. This works for numerical integration (quasi monte carlo integration), but also improves things like calculating treasure drops when a player kills a monster in a video game – see the previously mentioned youtube video for more info.

If you wanted to use these values in [0,1) to shuffle N items, you might think to multiply those values by N and clamp to [0,N-1), or something similar.

That works pretty well, but there are repeats! With an initial starting state of 0.55, here are 10 items shuffled:

5 1 7 4 0 6 2 8 4 1

That sequence has 1 and 4 twice, and misses 3 and 9.

There is a neat trick from Marc Reynolds to convert the golden ratio into an integer for when you want integer sequences (http://marc-b-reynolds.github.io/distribution/2020/01/24/Rank1Pre.html). He does it by multiplying the golden ratio by the number of integers there are and rounding to odd (round up or down, to whichever is the odd number). This treats the [0,N) integer range as if it were the real number range [0,1). It’s basically changing from working in floating point, to fixed point, and gives better results than using the golden ratio with conversion to integers.

That is nice, but doing that, it can still have repeats. Rounding to odd helps it have a longer period sequence, but it is not always a maximal period sequence. To make a maximal period sequence, we would need our integer approximation of the golden ratio to be coprime to the number of items in our shuffle.

We can search for such a number by checking if the number is coprime. If not, look at the number -1, then +1, then -2, then +2 and so on. We will eventually find the number coprime to N that most closely approximates the golden ratio. The farther we get from the golden ratio, the more our low discrepancy properties are degraded, so we want to be as close as possible.

To see if two numbers are coprime, you calculate their GCD (greatest common divisor), and they are coprime if the GCD is 1. You can calculate the GCD using Euclid’s algorithm and you can read about it at https://blog.demofox.org/2015/01/24/programmatically-calculating-gcd-and-lcm/.

Here’s the graph of the real number GoldenRatio*N (blue) and the integer coprime found (red) up to N=1000, you can see the coprime found is very close.

Here is a graph of the difference between the two. It never goes above 3.5.

So to make a low discrepancy shuffle iterator happens in two steps.

If we have an irrational number A, and want to shuffle N items, we find the integer coprime to N, which is closes to the real number (A*N). We’ll call this P.

Once we have P, we can call this function iteratively to get the next item in the shuffle:

unsigned int Shuffle_NextValue(unsigned int lastValue, unsigned int P, unsigned int N)

{

return (lastValue + P) % N;

}

To give this shuffle a random seed, the first time you call this function, give it a lastValue which is a random integer in [0,N).

Let’s look again at the golden ratio sequence before of 10 items which started at index 5 (a starting value of 0.548813522 for the LDS) and had some duplicates and missing items. We shuffled N=10 items, which gives us a coprime P=7, and we’ll start at index 5.

| Sequence | Duplicates | Missing | |

| LDS | 5 1 7 4 0 6 2 8 4 1 | 1 4 | 3 9 |

| Coprime | 5 2 9 6 3 0 7 4 1 8 | – | – |

The coprime approximation of the golden ratio gets rid of duplicates / missing values, while still being a nice low discrepancy sequence. Neighboring values are “very different” from each other.

Here is a 64 item shuffle with coprime P=41. The index started at 26, and the LDS started at 0.417021990.

| Sequence | Duplicates | Missing | |

| LDS | 26 2 41 17 56 32 8 47 23 62 38 13 53 28 4 44 19 59 34 10 49 25 0 40 15 55 31 6 46 21 61 36 12 51 27 3 42 18 57 33 8 48 23 63 39 14 54 29 5 44 20 59 35 11 50 26 1 41 16 56 31 7 47 22 | 8 23 26 31 41 44 47 56 59 | 9 24 30 37 43 45 52 58 60 |

| Coprime | 26 3 44 21 62 39 16 57 34 11 52 29 6 47 24 1 42 19 60 37 14 55 32 9 50 27 4 45 22 63 40 17 58 35 12 53 30 7 48 25 2 43 20 61 38 15 56 33 10 51 28 5 46 23 0 41 18 59 36 13 54 31 8 49 | – | – |

The code that goes with this post lets you see the error rate of LDS at different item counts and with different seeds, but the number of missing items in the LDS version of the shuffle is usually around 10-20%. The coprime version never misses any items, and is always pretty close to the integer (fixed point) approximation of the golden ratio.

Random Access

The code for the random access shuffle iterator is shown as an iterative process: you start at the first item and call Shuffle_NextValue() to get the next item. Rinse and repeat until you call it N times and the shuffle starts over.

The shuffle iterator does support random access though. If you want to know what item is at a specific shuffle index, the result is (index*P)%N. if index is a large enough number, you can start to hit problems with overflow though. To help this a bit, you can first modulus index by N, since the shuffle repeats itself every N steps.

That gives you this following code, which does give random access, but can still have integer overflow problems if index and N are large enough. So, be careful and take extra precautions when needed!

unsigned int Shuffle_RandomAccess(

unsigned int index,

unsigned int shuffleSeed,

unsigned int P,

unsigned int N)

{

return (((index % N) * P) + shuffleSeed) % N;

}

Inversion

If we want to know what location a specific item will show up in the shuffle, we can do that. Ignoring the integer overflow problems, and random seed for a moment, the formula for our random shuffle is this:

If we know item, P and N, and we want to know index, we are trying to calculate the “Modular Multiplicative Inverse”, which you can do using the “Extended Euclidean Algorithm”. It’s an iterative algorithm, but is not complicated or super expensive to calculate.

The extended euclidean algorithm tells you what you need to multiply P by to get 1. it gives you the x below.

Once you know how many steps it takes to get to 1, you can double it to get to 2, or triple it to get to 3 and so on. So if you want to know how many times it takes adding P to 0 to get to a specific number, you just multiply x by that number. That number may be much larger than N but you can just put it through modulo N since the sequence repeats every N times.

To handle the seed, you need to subtract out how many times you add P to 0 to get to the seed value.

In the end, the inversion algorithm looks like this:

uint Shuffle_GetIndexForValue(uint value, uint seed, uint coprime, uint numItems)

{

uint s, t;

ExtendedEuclidianAlgorithm(coprime, numItems, s, t);

uint stepsToValue = (t * value) % numItems;

uint stepsToSeed = (t * seed) % numItems;

return (stepsToValue + numItems - stepsToSeed) % numItems;

}

Notice on the last step we are adding an extra numItems before subtracting stepsToSeed. This is to handle the case where stepsToSeed is larger than stepsToValue and prevent integer underflow.

If you needed to do inversion often, you could store off that t value to make inversion lightning fast, without having to run the extended Euclidean algorithm each time.

You can read more about Modular Multiplicative Inverse at https://blog.demofox.org/2015/09/10/modular-multiplicative-inverse/.

Proof of Quality

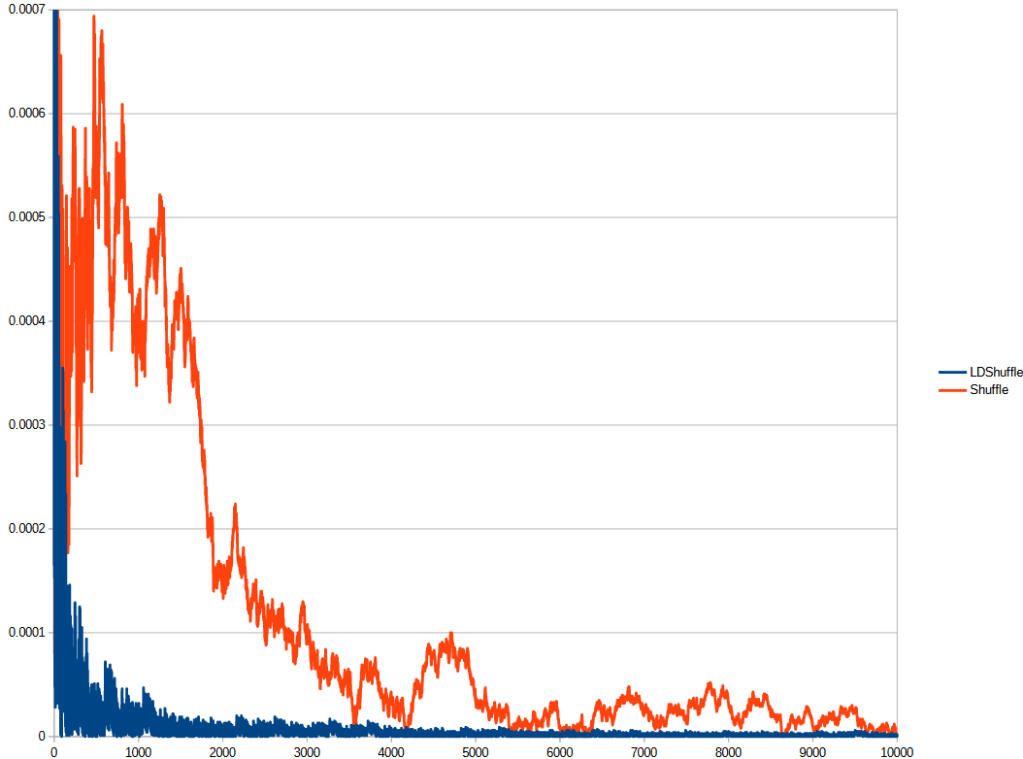

To help show why this shuffle is meaningful, we take 10,000 items valued 0 to 9,999, divide them by 9,999 to make them be between 0 and 1, and we iteratively average them from index 0 to index 1, index 2, index 3 and on up to index 9,999.

We do this for both a white noise shuffled array, and also this post’s low discrepancy shuffle iterator. We do that 1000 times and collect the average error.

Below is the graph of that data, which shows the low discrepancy shuffle iterator (blue) far outperforms the white noise shuffled array (orange). It gives a much better average much sooner which shows that it’s low discrepancy and has the desirable numerical properties we would expect from a golden ratio sequence, while still being a shuffle.

Hopefully you enjoyed this post. If you end up using this shuffle iterator for anything and see benefits, I’d love to hear about it here, or on mastodon, at https://mastodon.gamedev.place/@demofox

The C++ code that goes with this blog post can be found at https://github.com/Atrix256/GoldenRatioShuffle and includes a header file that contains a shuffler that should be easy to drop into other C++ code.

Here it is as shadercode (hlsl) as well:

// Example calculations

// 128x128 is 16384 pixels to shuffle, so numItems = 16384

// Coprime is 10127, calculated by code at that repo to be the coprime value closest to the golden ratio.

// StepsToUnity is 5999, calculated by code at that repo, using the chinese remainder theorem.

// Seed is the random seed of the shuffle, such as the constant "435".

// Return shuffle[index]

uint LDSShuffle1D_GetValueAtIndex(uint index, uint numItems, uint coprime, uint seed)

{

return ((index % numItems) * coprime + seed) % numItems;

}

// return the index where shuffle[index] == value

uint LDSShuffle1D_GetIndexOfValue(uint value, uint numItems, uint stepsToUnity, uint seed)

{

uint stepsToValue = (stepsToUnity * value) % numItems;

uint stepsToSeed = (stepsToUnity * seed) % numItems;

return (stepsToValue + numItems - stepsToSeed) % numItems;

}