In this post I’ll be showing two different ways to scale points along a specific direction (a vector). There isn’t anything novel here, but it gives an example of the type of math encountered in game development, and how you might approach a solution. The first method involves matrices, and the second involves vector projections.

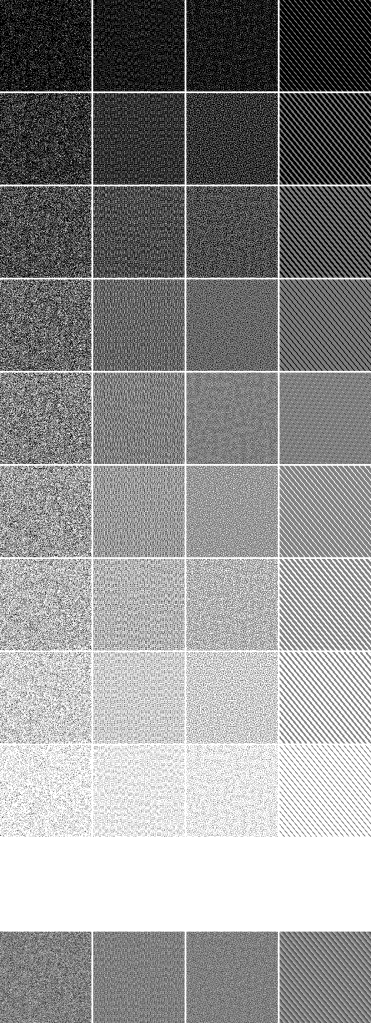

The points in the red circle below are scaled along the dark green vector, with the magnitude of the bright green vector.

The C++ code that made this diagram can be found at https://github.com/Atrix256/ScalePoints. It implements the vector projection method.

This problem came up for me when implementing a Petzval lens effect (https://bbhphoto.org/2017/04/24/the-petzval-lens/) in a bokeh depth of field (https://blog.demofox.org/2018/07/04/pathtraced-depth-of-field-bokeh/) post processing rendering technique. The setup is that I take point samples in the shape of the camera aperture for bokeh and depth of field, and I needed to stretch this sampled shape in a specific direction and magnitude, based on where the pixel is on the screen.

In the end, I just needed to scale points in a specific direction, by a specific amount. If we can do this operation to 1 point, we can do it to N points, so we’ll focus on doing this to a single point.

Method 1 – Matrices

Using matrices to scale a point along a specific direction involves three steps:

- Rotate the point so that the direction we want to scale is aligned with the X axis.

- Multiply the x axis value by the scaling amount.

- Unrotate the point back to the original orientation.

Our vectors are going to be row vectors. For a deep dive on other matrix and vector conventions and reasons to choose one way or another, read this great post by Jasper St. Pierre: https://blog.mecheye.net/2024/10/the-ultimate-guide-to-matrix-multiplication-and-ordering/

Let’s say we want to scale a point by 4 along the vector [3,1].

First we normalize that vector to [3/sqrt(10), 1/sqrt(10)]. Then we need to get the rotation matrix that will transform [3/sqrt(10), 1/sqrt(10)] to [1,0]. We can do that by making a matrix where the first column is where we want the x axis to point, and the second column to be where we want the y axis to point. For the x axis, we use the normalized vector we already have. For the y axis, we just need a perpendicular vector, which we can get by swapping the x and y components of the vector, and negating one to get [-1/sqrt(10), 3/sqrt(10)]. This operation of swapping x and y and negating one is sometimes called the “2D Cross Product” even though it isn’t really a cross product, and there is no cross product in 2D. That gives us this rotation matrix:

Next we need to make the scaling matrix, which we get by multiplying the vector [4,1] by the identity matrix:

Lastly we need to calculate the unrotation matrix. We need a matrix that rotates by the negative amount of R. We need the inverse matrix of R. The inverse of a rotation matrix is just the transpose matrix, so we can transpose R to make it. Another way to think about it is when we made the matrix before with the first column being the x axis and the second column being the y axis, we are now going to make the first row be the x axis, the second row be the y axis. Rows instead of columns. Whichever explanation makes most sense to you, we end up with this:

Now that we have all the transformations, we can calculate R * S * R’ to get a final matrix that does the transformation we want. I’ll do it in 2 steps in case that helps you follow along, to make sure you get the same numbers.

That is our matrix which scales a point along the vector [3,1], with a magnitude of 4. Let’s put the vector [4,5] through this transformation by multiplying it by the matrix.

For those who are counting instructions, processing a point using this process is 2 multiplies and two adds, to do that 2d vector / matrix product.

Creating the matrix took 16 multiplies and 8 adds (two matrix / matrix multiplies aka eight 2d dot products), but usually, you calculate a matrix like this once and re-use it for many points, which makes the matrix creation basically zero as a percentage of the total amount of calculations done, when amortized across all the points.

Method 2 – Vector Projection

I’m a fan of vector projection techniques. There is a certain intuitiveness in them that is missing from matrix operations, I find.

Using vector projection to scale a point along a specific direction involves these three steps:

- Project the point onto the scaling vector and multiply that by the scaling amount.

- Project the point onto the perpendicular vector.

- Add the scaling vector projection times the scaling vector to the perpendicular vector projection times the perpendicular vector.

We will use the same values from the last section, so we want to scale a point by 4 along the vector [3,1], which we normalize to [3/sqrt(10), 1/sqrt(10)]. We will put the point [4, 5] through this process.

Step 1 is to project our point onto the scaling vector. We do that by doing a dot product between our normalized vector [3/sqrt(10), 1/sqrt(10)], and our point [4, 5]. That gives us the value 17/sqrt(10). We then multiply that by the scaling amount 4 to get 68/sqrt(10).

Step 2 is to project our point onto the perpendicular vector. We can once again use the “2D Cross Product” to get the perpendicular vector. We just flip the x and y component and negate one, to get the vector perpendicular to the scaling vector: [-1/sqrt(10), 3/sqrt(10)]. We can dot product that with our point [4, 5] to get: 11/sqrt(10).

Step 3 is to multiply our projections by the vectors we projected onto, and add the results together. Our scaling vector contribution is 68/sqrt(10) * [3/sqrt(10), 1/sqrt(10)] or [204/10, 68/10]. Our perpendicular vector contribution is 11/sqrt(10)*[-1/sqrt(10), 3/sqrt(10)] or [-11/10, 33/10].

When we add the two values together, we get [193/10, 101/10] or [19.3, 10.1].

That result matches what we got with the matrix operations!

As far as instruction counts, we did two dot products for step 1 and 2 which is 4 multiplies and 2 adds total. Step 3 is 4 multiplies. Step 4 is 2 multiplies and 2 adds. This is a total of 10 multiplies and 4 adds which is a lot more than the matrix version, which was just 2 multiplies and 2 adds.

If you optimized this process to do fewer operations by combining work where you could, you’d eventually end up at the same operations done in the matrix math. Algebra is fun that way.

Higher Dimensions?

Using the matrix method in higher dimensions, making the scaling vector is easy, and making the unrotation matrix is still just taking the transpose of the rotation matrix. It’s more difficult making the rotation matrix though.

In 3D, the scaling direction will be a 3D vector, and you need to come up with two other vectors that are perpendicular to that scaling direction. One way to do this could be to take any vector which is different from the scaling vector, and cross product that with the scaling vector. That will give you a vector perpendicular to both, and you can take that as your second vector. To get the third vector, cross product that vector with the scaling vector. You will then have 3 perpendicular vectors, and an orthonormal basis that you can use to fill out your rotation matrix. The first column is the scaling vector, the second column is the second vector found, and the third column is the third column found.

The cross product only exists in the 3rd and 7th dimension though, so if you are working in a different dimension, or if you don’t want to use the cross product for some reason, another way you can make an orthonormal basis is by using the Gram-Schmidt process. There’s a great video on it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOkuTXrv5Gg

For the vector project method, you also need the orthonormal basis vectors to do all the vector projections, before you scale the x axis, and then re-combine the projections, so it boils down to the same issues as the matrix method.

From Readers

Nick Appleton (https://mastodon.gamedev.place/@nickappleton) says:

shameless plug of my last blog post (regarding higher order rotation matrices) https://www.appletonaudio.com/blog/2023/high-dimension-rotation-matrices/

This has methods for generating a high order rotation that moves a point to a particular axis. There is rarely a need need for a Gram Schmidt process and computing the matrix can be made quite cheap 🙂

I think the most efficient way to find a rotation matrix that takes a unit vector A and moves it to another unit vector B (in any dimension) is to find the find the reflection matrix that maps A to C (where C=B with a single component negated – doesn’t matter which one) and then flip the sign of the corresponding row of the matrix to turn it into a rotation.

Finding a reflection matrix that does this requires only a single division in an efficient implementation for any dimension.

Mastodon link: https://mastodon.gamedev.place/@nickappleton/113315462425042217

Andrew Gang (https://vis.social/@pteromys) says:

if your use case doesn’t need accuracy for scaling amounts near zero, method 2 has a variant that saves you from having to find perpendicular vectors: point + (scaling amount – 1) * dot(normalized scaling vector, point) * normalized scaling vector.

Mastodon link: https://vis.social/@pteromys/113317364225437813