Homomorphic encryption is a pretty interesting thing. It allows you to do calculations on encrypted data such that when you decrypt the results, it’s as if you did the calculations on the unencrypted data. This allows computation to happen without the person doing the computation knowing what the data actually is!

Brief History

For a long time, cryptographers wondered if fully homomorphic encryption was even possible. There were various encryption algorithms that could perform SOME operations homomorphically (RSA can do multiplication for instance!), but there weren’t any that could do ALL operations. In other words, you couldn’t execute arbitrary computations.

Those types of algorithms are called “Partially Homomorphic Encryption” or PHE.

Another problem standing in the way of fully homomorphic encryption was that many algorithms would only have a limited count of operations they could perform before error would accumulate and they would start giving incorrect answers. In essence they were limited to evaluating low degree polynomials.

Those types of algorithms are called “Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption” or SWHE.

In contrast, Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) can perform an unlimited number of homomorphic operations, and it can perform any operation homomorphically. It is unbounded in both ways.

Amazingly, In 2009 Craig Gentry figured out the first fully homomorphic encryption scheme! With his setup, you can calculate both XOR and AND on encrypted bits, which makes it Turing complete. It is also able to keep errors from becoming too large by using an ingenious bootstrapping technique to decrease accumulated error. Here’s a link to his PHd thesis: A Fully Homomorphic Encryption Scheme.

Unfortunately, the current implementations of secure FHE take too much computational power to be practical in most situations – like 30 minutes to calculate an AND between 2 bits!

In this post I’m going to show you a super simple HE implementation that will be very easy to understand. It won’t be fully homomorphic, but it will be “leveled” (or, somewhat homomorphic), meaning it is Turing complete, but the count of calculations you can perform are limited due to error creeping in. It also won’t be secure – due to making it easy to understand – but it will be lightning fast.

This will be a symmetric key algorithm, but as we’ll explore in future posts, it can also be used for public key algorithms.

Why Is HE Useful?

One thing you could do with HE is store your financial transactions encrypted on a server. The server could run queries and calculations on your financial data and send back the results. You could then unencrypt the result and see what the values are, even though the server itself – which generated the values – has no idea what the numbers actually are.

Another use could be in games. Whether you are playing a first person shooter, or a real time strategy game, many different types of games send information about each player to every other player in the game. Hashes of game state can be used to make sure that everyone is in agreement about calculations to prevent a player from cheating by WRITING to a value they shouldn’t be writing to (or, at least you can detect when they do, and use majority rule to boot them out of the game), but how do you stop a player from READING a value they shouldn’t be reading?

Using HE, you could encrypt the data you need to send to players that they shouldn’t be able to read. With this, they could still do game play logic calculations on the data, and calculate hashes of the encrypted results to ensure that all players were in agreement, but with HE, they wouldn’t gain knowledge of the data they were working with.

In other words, player A could verify that player B’s state is correct and they haven’t cheated, without player A getting details about player B’s state.

In theory this could eliminate or at least help combat things like wall hacks and other “data read” based cheats. In practice there would be some complications to work out, even if it wasn’t crazy slow to calculate, but the fact that there is a path to addressing these issues is pretty exciting! People are working on improving speed, and games don’t need the same level of security that other usage cases do.

How To Do It

Here are the details of this super simple leveled homomorphic symmetric key algorithm.

By the way, all the percent signs below mean “modulus” which is just the remainder of a division. 25 % 4 = 1 for instance, because 25/4 = 6 with a remainder of 1. That remainder of 1 is what we get when we take the modulus. A term you’ll see more often if reading through this stuff on your own will be “residue”. Don’t let that word scare you, it is just another name for the remainder.

Making A Secret Key

To make a key, generate an odd random number between 2^(N-1) and 2^N. In other words, it will be N random bits, except the highest and lowest bit will be set to 1. N is the size of your secret key. Larger keys are more secure, and allow more computations to be done in a row, but they also take more storage space. If you are using a fixed size int – like say a uint32 – a larger key will make you run out of those 32 bits sooner.

key = RandomNumber(0, (1 << N) - 1) | 1 | (1 << (N - 1));

Encrypt

To encrypt a bit, the encrypted value is just the key plus the value of the unencrypted bit (0 or 1).

encryptedBit = key + value ? 1 : 0;

Decrypt

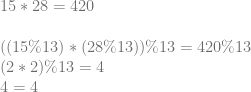

To decrypt a bit, you take the encrypted bit modulo the key, and then modulo 2.

decryptedBit = (encryptedBit % key) % 2;

XOR

To do an XOR of two encrypted bits, you just add the two values together.

xorResult = encryptedBit1 + encryptedBit2;

AND

To do an AND of two encrypted bits, you just multiply the two values together.

andResult = encryptedBit1 * encryptedBit2;

Example

Let’s run through an example to see this in action.

We’ll use a 4 bit key, and say that the key is 13 (1101 in binary).

Let’s encrypt some bits:

Let’s do some logical operations:

Notice how AND is a multiplication where XOR is an addition, and that the result of an AND operation is a larger number than an XOR operation. This means that if you are working with a specific sized number (again, such as a uint32), that you can do fewer ANDs than XORs before you run out of bits. When you run out of bits and your number has integer overflow, you have hit the cieling of this leveled HE scheme. That means that ANDs are more expensive than XORs when considering the number of computations you can do.

Ok, time to decrypt our XOR values!

XOR is looking correct, how about AND?

AND is looking good as well. Lastly let’s decrypt the compound operation:

Lookin good!

Intuition

Let’s get some intuition for why this works…

Key Generation

First up, why is it that the key needs to have it’s high bit set? Well, on one hand, larger keys are more secure, and allow more room for error accumulation so allow more operations to be done. On the other hand, this is kind of misleading to say. If you generate ANY random odd integer, there will be a highest bit set to 1 SOMEWHERE. You technically don’t need to store the zeros above that. So i guess you could look at it like you are just generating ANY random odd integer, and you could figure out N FROM that value (the position of the highest bit). Thinking about it the way we do though, it lets us specify how many bits we actually want to commit to for the key which gives us more consistent behavior, upper bound storage space, etc.

Secondly, why does the key need to be odd?

Let’s say that you have two numbers A and B where A represents an encrypted bit and B represents the encryption key. If B is even, then A % B will always have the same parity (whether it’s even or odd) as A. Since we are trying to hide whether our encrypted bit is 0 or 1 (even or odd), that makes it very bad encryption since you can recover the plain text bit by doing encryptedValue % 2. If on the other hand, B is odd, A % B will have the same parity as A only if A / B is even.

This doesn’t really make much of a difference in the scheme in this post, because A / B will always be 1 (since the encrypted bit is the key plus the plain text bit), but in the next scheme it is more important because A / B will be a random number, which means that it will be random with a 50/50 chance whether or not the parity of the encrypted bit matches the parity of the plain text bit. Since it’s an even chance whether it matches or not, that means that an attacker can’t use that information to their advantage.

While it’s true that when generating a random key, there is a 50/50 chance of whether you will get an even or odd key, you can see how we’d be in a situation where 75% of the time the parity of the ciphertext would match the parity of the plaintext if we allowed both even and off keys.

That would mean that while an attacker couldn’t know for CERTAIN whether an encrypted bit is 1 or 0 based on the cipher text, they can guess with 75% confidence that the unencrypted bit will just be the cipher text % 2, which is no good! So, we are better off sticking with an odd numbered key in this scheme. But again, that won’t really matter until the next post!

XOR as Addition

I know that I’m going to butcher this explanation a bit in the eyes of someone who knows this math stuff better than me. If you are reading this and see that I have indeed done that, please drop me a line or leave a comment and let me know what I’ve missed or could explain better. I suspect there’s something about rings going on here (;

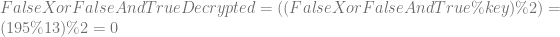

Believe it or not, when you add two numbers together and then take the modulus, you get the same answer as if you did the modulus on the two numbers, added them together, and then took the modulus again.

In other words, adding two numbers can be seen as adding their residue (remainder).

Let me show you an example.

Let’s try another one. I’m picking these numbers “randomly” out of my head 😛

OK makes sense, but who cares about that?

Well, believe it or not, 1 bit addition is the same as XOR! This means that you can add numbers together, which adds the modulus of their key together, which then in turn adds that number mod 2 together, to preserve the encrypted parity (odd or even-ness).

Check out this 2 bit binary math. Keep in mind that with 1 bit results, you would only keep the right most binary digit. I’m showing two digits to show you that it is in fact binary addition, and that the right most bit is in fact the same as XOR.

One thing to note before we move on is that since we are doing a modulus against the key, when the remainder gets to be too large it rolls over. When it rolls over, we start getting the wrong answers and have hit our ceiling of how many operations we can do. So, our encrypted value modulo the key divided by the key can be seen as where we are at by percentage towards our error ceiling.

To avoid hitting the problem of error getting too high too quickly and limiting your calculation count too much you can increase the key size. When you do that you’ll then run out of bits in your fixed size integer storage faster. To avoid THAT problem you can use “multi precision math libraries” to allow your integers to use an arbitrary number of bytes. This is what many real crypto algorithms use when they need to deal with very large numbers.

AND as Multiplication

Similar to the above, when you multiply two numbers and take a modulus of the result, it’s the same as if you took the modulus of the two numbers, multiplied that, and then took the modulus of the result.

In other words, when you multiply two numbers, you can think of it as also multiplying their residue (remainder).

Using the first example numbers from above:

And the second:

A bit of a coincidence that they both worked out to 4 this time 😛

Similar to XOR being the same as 1 bit addition, 1 bit multiplication is actually the same as AND, check it out:

Since AND multiplies residue, and XOR adds residue, and residue is what limits our homomorphic instruction count, you can see that AND is a more expensive operation compared to XOR, since it eats into our instruction budget a lot faster.

Error In Action

To see why rolling over is a problem, let’s say that our key is 9 and we want to XOR two encrypted bits 8 and 1, which represent 0 and 1 respectively.

To do an XOR, we add them together: 8 + 1 = 9.

Now, when we decrypt it we do this: (9 % 9) % 2 = 0

That result tells us that 0 XOR 1 is 0, which is incorrect! Our residue got too large and we hit the ceiling of our homomorphic instruction budget.

If the first bit was 6 instead of 8, the result of the XOR would have been 7, and (7 % 9) % 2 comes out to 1. That re-affirms to us that if we are under the error budget, we are good to go, but if our residue gets too large, we will have problems!

Sample Code

// Note that this encryption scheme is insecure so please don't actually use it

// in production! A false bit with a given key is the same value every time, and

// so is a true bit. Also, the encrypted true bit value will always be the

// encrypted false bit plus 1. Even worse, an encrypted false bit is the key itself!

// This is just for demonstration purposes to see how the basics of homomorphic

// encryption work. The next blog post will increase security.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <random>

#include <array>

#include <inttypes.h>

typedef uint64_t uint64;

// Increase this value to increase the size of the key, and also the maximum

// size of the error allowed.

// If you set it too high, operations will fail when they run out of storage space

// in the 64 bit ints. If you set it too low, you will not be able to do very many

// operations in a row.

const size_t c_numKeyBits = 6;

#define Assert(x) if (!(x)) ((int*)nullptr)[0] = 0;

//=================================================================================

// TODO: Replace with something crypto secure if desired!

uint64 RandomUint64 (uint64 min, uint64 max)

{

static std::random_device rd;

static std::mt19937 gen(rd());

std::uniform_int_distribution<uint64> dis(min, max);

return dis(gen);

}

//=================================================================================

void WaitForEnter ()

{

printf("Press Enter to quit");

fflush(stdin);

getchar();

}

//=================================================================================

uint64 GenerateKey ()

{

// Generate an odd random number in [2^(N-1), 2^N)

// N is the number of bits in our key

// The key also defines the maximum amount of error allowed, and thus the number

// of operations allowed in a row.

return RandomUint64(0, (1 << c_numKeyBits) - 1) | 1 | (1 << (c_numKeyBits - 1));

}

//=================================================================================

bool Decrypt (uint64 key, uint64 value)

{

return ((value % key) % 2) == 1;

}

//=================================================================================

uint64 Encrypt (uint64 key, bool value)

{

uint64 ret = key + (value ? 1 : 0);

Assert(Decrypt(key, ret) == value);

return ret;

}

//=================================================================================

uint64 XOR (uint64 A, uint64 B)

{

return A + B;

}

//=================================================================================

uint64 AND (uint64 A, uint64 B)

{

return A * B;

}

//=================================================================================

int GetErrorPercent (uint64 key, uint64 value)

{

// Returns what % of maximum error this value has in it. When error >= 100%

// then we have hit our limit and start getting wrong answers.

return int(100.0f * float(value % key) / float(key));

}

//=================================================================================

uint64 FullAdder (uint64 A, uint64 B, uint64 &carryBit)

{

// homomorphically add the encrypted bits A and B

// return the single bit sum, and put the carry bit into carryBit

// From http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Adder_(electronics)&oldid=381607326#Full_adder

uint64 sumBit = XOR(XOR(A, B), carryBit);

carryBit = XOR(AND(A, B), AND(carryBit, XOR(A, B)));

return sumBit;

}

//=================================================================================

int main (int argc, char **argv)

{

// run this test a bunch to show that it works. If you get a divide by zero

// in an Assert, that means that it failed, and hopefully it's because you

// increased c_numKeyBits to be too large!

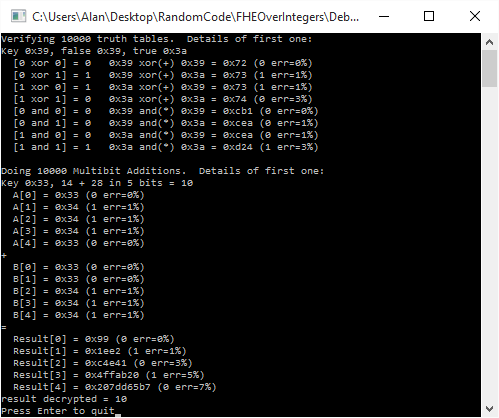

printf("Verifying 10000 truth tables. Details of first one:n");

for (int index = 0; index < 10000; ++index)

{

// make our key and a true and false bit

uint64 key = GenerateKey();

uint64 falseBit = Encrypt(key, false);

uint64 trueBit = Encrypt(key, true);

// Verify truth tables for XOR and AND

Assert(Decrypt(key, XOR(falseBit, falseBit)) == false);

Assert(Decrypt(key, XOR(falseBit, trueBit )) == true );

Assert(Decrypt(key, XOR(trueBit , falseBit)) == true );

Assert(Decrypt(key, XOR(trueBit , trueBit )) == false);

Assert(Decrypt(key, AND(falseBit, falseBit)) == false);

Assert(Decrypt(key, AND(falseBit, trueBit )) == false);

Assert(Decrypt(key, AND(trueBit , falseBit)) == false);

Assert(Decrypt(key, AND(trueBit , trueBit )) == true );

// report the results for the first iteration of the loop

if (index == 0)

{

printf("Key 0x%" PRIx64 ", false 0x%" PRIx64 ", true 0x%" PRIx64 "n", key, falseBit, trueBit);

printf(" [0 xor 0] = 0 0x%" PRIx64 " xor(+) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", falseBit, falseBit, XOR(falseBit, falseBit), Decrypt(key, XOR(falseBit, falseBit)) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(falseBit, falseBit)));

printf(" [0 xor 1] = 1 0x%" PRIx64 " xor(+) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", falseBit, trueBit , XOR(falseBit, trueBit ), Decrypt(key, XOR(falseBit, trueBit )) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(falseBit, trueBit )));

printf(" [1 xor 0] = 1 0x%" PRIx64 " xor(+) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", trueBit , falseBit, XOR(trueBit , falseBit), Decrypt(key, XOR(trueBit , falseBit)) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(trueBit , falseBit)));

printf(" [1 xor 1] = 0 0x%" PRIx64 " xor(+) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", trueBit , trueBit , XOR(trueBit , trueBit ), Decrypt(key, XOR(trueBit , trueBit )) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(trueBit , trueBit )));

printf(" [0 and 0] = 0 0x%" PRIx64 " and(*) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", falseBit, falseBit, AND(falseBit, falseBit), Decrypt(key, AND(falseBit, falseBit)) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(falseBit, falseBit)));

printf(" [0 and 1] = 0 0x%" PRIx64 " and(*) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", falseBit, trueBit , AND(falseBit, trueBit ), Decrypt(key, AND(falseBit, trueBit )) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(falseBit, trueBit )));

printf(" [1 and 0] = 0 0x%" PRIx64 " and(*) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", trueBit , falseBit, AND(trueBit , falseBit), Decrypt(key, AND(trueBit , falseBit)) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(trueBit , falseBit)));

printf(" [1 and 1] = 1 0x%" PRIx64 " and(*) 0x%" PRIx64 " = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", trueBit , trueBit , AND(trueBit , trueBit ), Decrypt(key, AND(trueBit , trueBit )) ? 1 : 0, GetErrorPercent(key, XOR(trueBit , trueBit )));

}

}

// Do multi bit addition as an example of using compound circuits to

// do meaningful work.

const size_t c_numBitsAdded = 5;

printf("nDoing 10000 Multibit Additions. Details of first one:n");

std::array<uint64, c_numBitsAdded> numberAEncrypted;

std::array<uint64, c_numBitsAdded> numberBEncrypted;

std::array<uint64, c_numBitsAdded> resultEncrypted;

for (int index = 0; index < 10000; ++index)

{

// generate the numbers we want to add

uint64 numberA = RandomUint64(0, (1 << c_numBitsAdded) - 1);

uint64 numberB = RandomUint64(0, (1 << c_numBitsAdded) - 1);

// generate our key

uint64 key = GenerateKey();

// encrypt our bits

for (int bitIndex = 0; bitIndex < c_numBitsAdded; ++bitIndex)

{

numberAEncrypted[bitIndex] = Encrypt(key, (numberA & (uint64(1) << uint64(bitIndex))) != 0);

numberBEncrypted[bitIndex] = Encrypt(key, (numberB & (uint64(1) << uint64(bitIndex))) != 0);

}

// do our multi bit addition!

// we could initialize the carry bit to 0 or the encrypted value of 0. either one works since 0 and 1

// are also poor encryptions of 0 and 1 in this scheme!

uint64 carryBit = Encrypt(key, false);

for (int bitIndex = 0; bitIndex < c_numBitsAdded; ++bitIndex)

resultEncrypted[bitIndex] = FullAdder(numberAEncrypted[bitIndex], numberBEncrypted[bitIndex], carryBit);

// decrypt our result

uint64 resultDecrypted = 0;

for (int bitIndex = 0; bitIndex < c_numBitsAdded; ++bitIndex)

{

if (Decrypt(key, resultEncrypted[bitIndex]))

resultDecrypted |= uint64(1) << uint64(bitIndex);

}

// make sure that the results match, keeping in mind that the 4 bit encryption may have rolled over

Assert(resultDecrypted == ((numberA + numberB) % (1 << c_numBitsAdded)));

// report the results for the first iteration of the loop

if (index == 0)

{

printf("Key 0x%" PRIx64 ", %" PRId64 " + %" PRId64 " in %i bits = %" PRId64 "n", key, numberA, numberB, c_numBitsAdded, (numberA + numberB) % (1 << c_numBitsAdded));

for (int bitIndex = 0; bitIndex < c_numBitsAdded; ++bitIndex)

printf(" A[%i] = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", bitIndex, numberAEncrypted[bitIndex], Decrypt(key, numberAEncrypted[bitIndex]), GetErrorPercent(key, numberAEncrypted[bitIndex]));

printf("+n");

for (int bitIndex = 0; bitIndex < c_numBitsAdded; ++bitIndex)

printf(" B[%i] = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", bitIndex, numberBEncrypted[bitIndex], Decrypt(key, numberBEncrypted[bitIndex]), GetErrorPercent(key, numberBEncrypted[bitIndex]));

printf("=n");

for (int bitIndex = 0; bitIndex < c_numBitsAdded; ++bitIndex)

printf(" Result[%i] = 0x%" PRIx64 " (%i err=%i%%)n", bitIndex, resultEncrypted[bitIndex], Decrypt(key, resultEncrypted[bitIndex]), GetErrorPercent(key, resultEncrypted[bitIndex]));

printf("result decrypted = %" PRId64 "n", resultDecrypted);

}

}

WaitForEnter();

return 0;

}

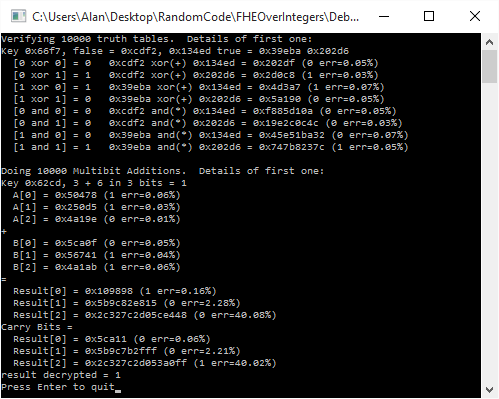

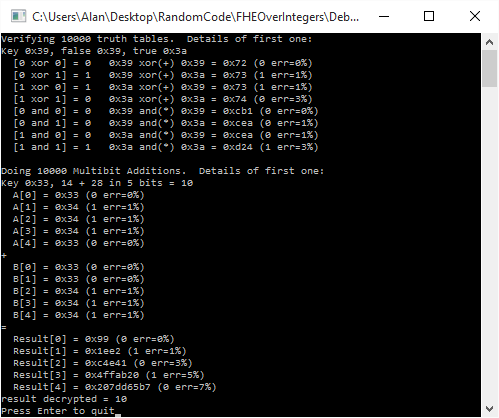

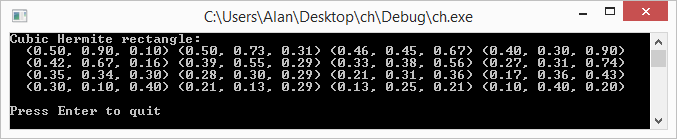

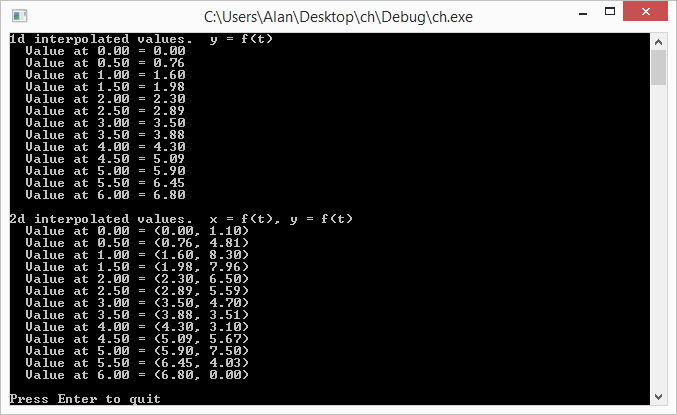

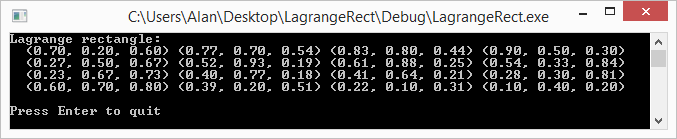

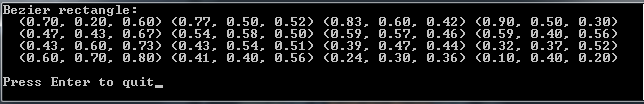

Here is the output of a run of the program:

What if I Need Constants?!

If you are thinking how you might actually use this code in a real setting, you might be thinking to yourself “it’s great to be able to multiply two encrypted numbers together, but what if I just need to multiply them by a constant like 43?”

Well, interestingly, you can literally just use 0 and 1 in this scheme as constants to perform operations against the encrypted bits.

The reason that this works is that you can see 0 and 1 as just very poor encryptions 😛

(0 % KEY) % 2 = 0

(1 % KEY) % 2 = 1

As long as KEY is >= 2, the above is always true, no matter what the key actually is!

So there you go, add your own constants into the calculations all you want. They also happen to have very low residue/error (actually, they have the least amount possible!), so are much more friendly to use, versus having someone provide you with an encrypted table of constants to use in your calculations. It’s also more secure for the person doing the encrypting for them to provide you less encrypted data that you know the plain text for. It limits your (and anyone else’s) ability to do a known plain text attack.

The Other Shoe Drops

You might notice that in our scheme, given the same key, every true bit will be the same value, and every false bit will be the same value. Unfortunately, the true bit is also always the false bit + 1. As an attacker, this means that once you have seen both a true bit and a false bit, you will then have broken the encryption.

Even worse, when you encrypt a false bit, it gives you back the key itself!

We’ll improve that in the next post by adding a few more simple operations to the encryption process.

This leveled HE encryption scheme comes directly from the paper below. If you want to give it a look, what we covered is only part of the first two pages!

Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Integers

The links below are where I started reading up on HE. They go a different route with FHE that you might find interesting, and also have a lot more commentary about the usage cases of HE:

The Swiss Army Knife of Cryptography

Building the Swiss Army Knife

In the scheme in those links, I haven’t figured out how multiplication is supposed to work yet (or bootstrapping, but one thing at a time). If you figure it out, let me know!

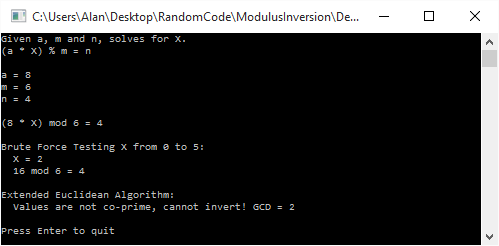

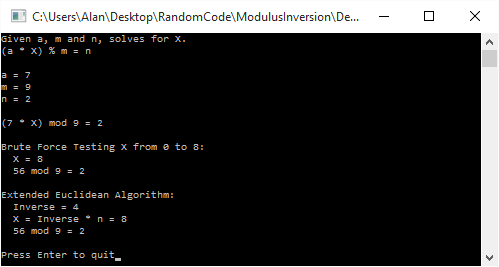

, to come up with a value of 8 for x.

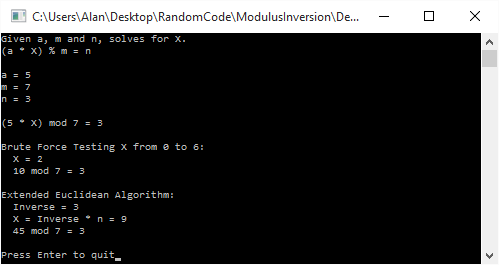

. Brute force gives us a value of 2 for x, while the inverse gives us a value of 9. Both are valid, and in fact are equivalent since 9 % 7 = 2. This shows that getting the inverse and then multiplying it to get the desired answer doesn’t always give you the smallest possible value of x.

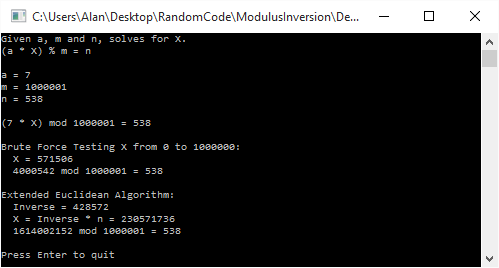

. Brute force gives a value of 571,506 for x, while using the inversion method gives us a value of 230,571,736.

. Brute force gives us a value of 2 for x, but interestingly, it isn’t invertible, so the inversion based solution can’t even find us an answer!