If you were asked to name a line drawing algorithm, chances are you would say Bresenham. I recently needed to write my own software line drawing algorithm (CPU and regular ram, not GPU and VRAM) and Bresenham was the first to come to mind for me as well.

Believe it or not, Jack Bresenham actually came up with 2 famous line drawing algorithms. One is a run length algorithm, and the other is a run slice algorithm. People are most often familiar with the run length algorithm, which I mainly talk about in this post, but there’s some information about the run slice algorithm and links to other Bresenham primitive rendering algorithms below as well!

An interesting thing about both line algorithms is that they involve only integer mathematics, so there is no round off error, epsilons, numerical instability or anything like that. You use only integers and simple math (no divisions even!), and get the exact right answer out. I think that is pretty cool.

Bresenham’s Run Length Line Algorithm Summarized

To help understand the code, I want to give a brief summarization of how the algorithm works at a high level.

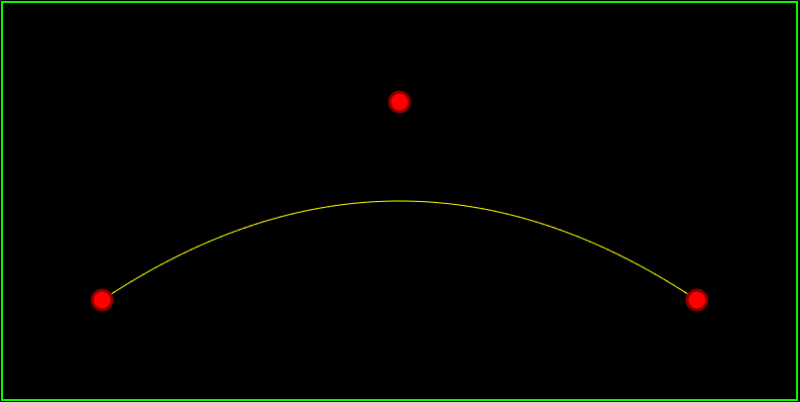

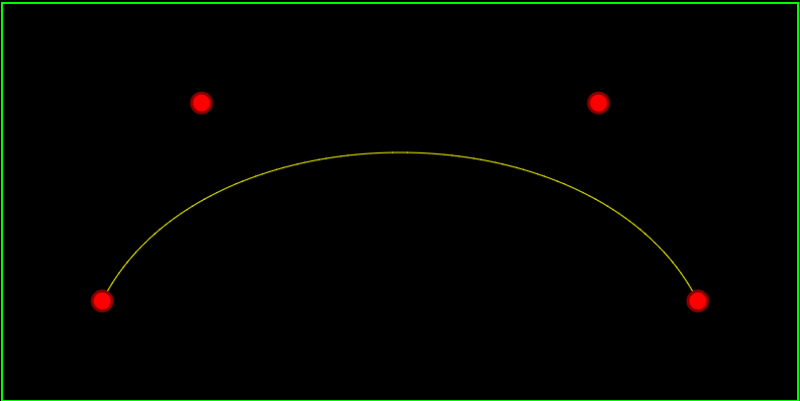

The first step of the Bresenham line algorithm is to see if the line is longer on the X axis or Y axis. Whichever one it is longer on is the major axis, and the shorter one is the minor axis.

Then, starting at the starting point of the line, you loop across all pixels of the major axis, doing some math to decide for each pixel whether you need to move the pixel on the minor axis yet or not. Basically you keep track of the error – or the distance the pixel is away from the true position of the line on the minor axis – and if the error is greater than or equal to 1 pixel, you move the pixel on the minor axis and subtract one pixel from the error. If the error is smaller than 1 pixel, you keep it at the same value it was for the last pixel, and keep the error value the same, so that it can accumulate some more error for the next pixel and test again.

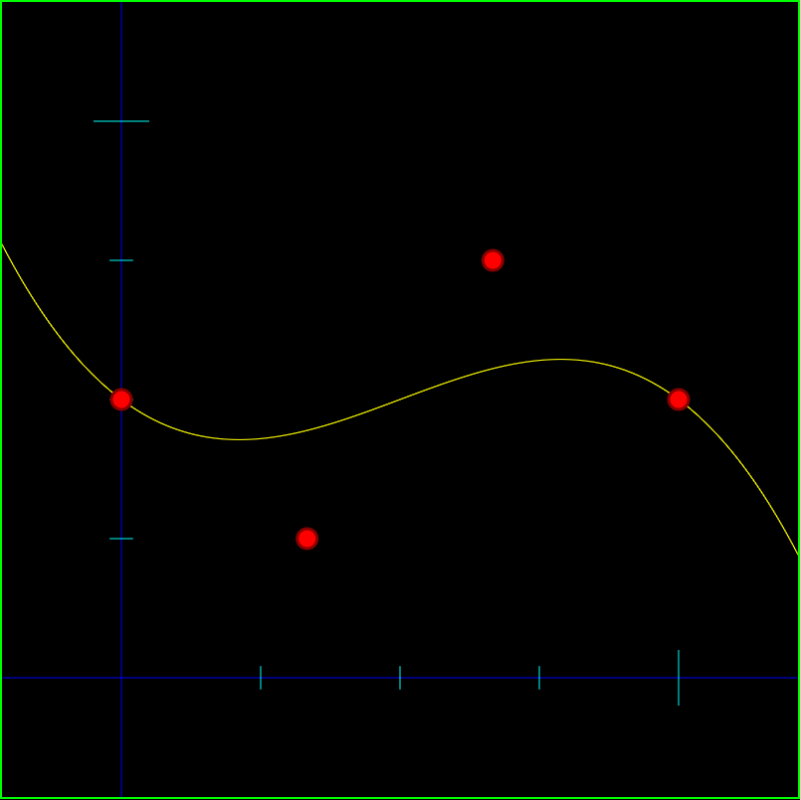

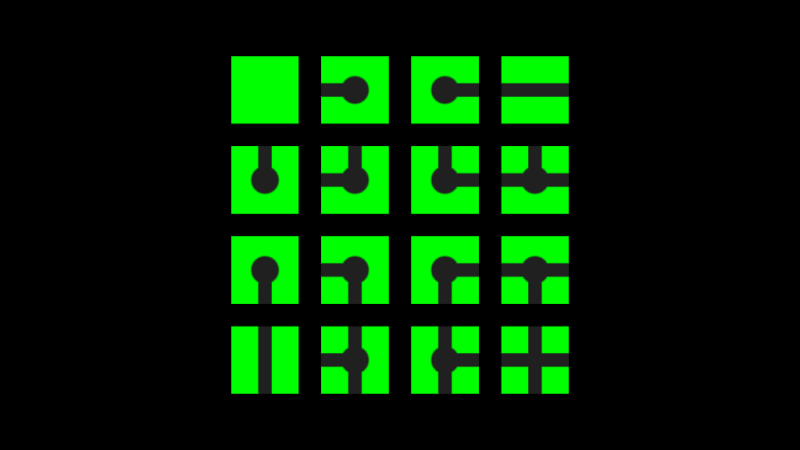

The left line is longer on the X axis, so the major axis is the X axis. The right line is longer on the Y axis, so the major axis is the Y axis. Notice that there is one pixel for each value along the major axis of each line, but repeated pixel values along the minor axis of each line.

If you want the deeper details about the algorithm or the math behind it, check out this link:

Wikipedia: Bresenham’s line algorithm

One Octant Code

Wikipedia says that many implementations implement the algorithm for a single octant (half of a quadrant) and then use coordinate conversions (flipping the x and y’s and/or negating them) to make the same logic work for any quadrant.

In that vein, here is a simple implementation for the first octant – where the major axis is X, and both X and Y are increasing from the starting point to the ending point.

void DrawLine (int x1, int y1, int x2, int y2, unsigned int color)

{

const int dx = x2 - x1;

const int dy = y2 - y1;

int Error = 2 * dy - dx;

int y = y1;

DrawPixel(x1, y1, color);

for (int x = x1+1; x < x2; ++x)

{

if (Error > 0)

{

y++;

Error += 2 * dy - 2 * dx;

}

else

{

Error += 2 * dy;

}

DrawPixel(x,y,color);

}

}

With the point of Bresenham being that it is efficient, let’s sacrifice readability a bit and get rid of those DrawPixel calls and perhaps over-micro-optimize a bit and make some consts for frequently used values.

void DrawLine (unsigned int* pixels, int width, int x1, int y1, int x2, int y2, unsigned int color)

{

const int dx = x2 - x1;

const int dy = y2 - y1;

const int dx2 = dx * 2;

const int dy2 = dy * 2;

const int dy2Mindx2 = dy2 - dx2;

int Error = dy2 - dx;

unsigned int* pixel = &pixels[y1*width+x1];

*pixel = color;

for (int x = x2 - x1 - 1; x > 0; --x)

{

if (Error > 0)

{

pixel += width + 1;

Error += dy2Mindx2;

}

else

{

pixel++;

Error += dy2;

}

*pixel = color;

}

}

Cool, now let’s make it work for any line.

Final Code

// Generic Line Drawing

// X and Y are flipped for Y maxor axis lines, but the pixel writes are handled correctly due to

// minor and major axis pixel movement

void DrawLineMajorAxis(

unsigned int* pixel,

int majorAxisPixelMovement,

int minorAxisPixelMovement,

int dx,

int dy,

unsigned int color

)

{

// calculate some constants

const int dx2 = dx * 2;

const int dy2 = dy * 2;

const int dy2Mindx2 = dy2 - dx2;

// calculate the starting error value

int Error = dy2 - dx;

// draw the first pixel

*pixel = color;

// loop across the major axis

while (dx--)

{

// move on major axis and minor axis

if (Error > 0)

{

pixel += majorAxisPixelMovement + minorAxisPixelMovement;

Error += dy2Mindx2;

}

// move on major axis only

else

{

pixel += majorAxisPixelMovement;

Error += dy2;

}

// draw the next pixel

*pixel = color;

}

}

// Specialized Line Drawing optimized for horizontal or vertical lines

// X and Y are flipped for Y maxor axis lines, but the pixel writes are handled correctly due to

// minor and major axis pixel movement

void DrawLineSingleAxis(unsigned int* pixel, int majorAxisPixelMovement, int dx, unsigned int color)

{

// draw the first pixel

*pixel = color;

// loop across the major axis and draw the rest of the pixels

while (dx--)

{

pixel += majorAxisPixelMovement;

*pixel = color;

};

}

// Draw an arbitrary line. Assumes start and end point are within valid range

// pixels is a pointer to where the pixels you want to draw to start aka (0,0)

// pixelStride is the number of unsigned ints to get from one row of pixels to the next.

// Usually, that is the same as the width of the image you are drawing to, but sometimes is not.

void DrawLine(unsigned int* pixels, int pixelStride, int x1, int y1, int x2, int y2, unsigned int color)

{

// calculate our deltas

int dx = x2 - x1;

int dy = y2 - y1;

// if the X axis is the major axis

if (abs(dx) >= abs(dy))

{

// if x2 < x1, flip the points to have fewer special cases

if (dx < 0)

{

dx *= -1;

dy *= -1;

swap(x1, x2);

swap(y1, y2);

}

// get the address of the pixel at (x1,y1)

unsigned int* startPixel = &pixels[y1 * pixelStride + x1];

// determine special cases

if (dy > 0)

DrawLineMajorAxis(startPixel, 1, pixelStride, dx, dy, color);

else if (dy < 0)

DrawLineMajorAxis(startPixel, 1, -pixelStride, dx, -dy, color);

else

DrawLineSingleAxis(startPixel, 1, dx, color);

}

// else the Y axis is the major axis

else

{

// if y2 < y1, flip the points to have fewer special cases

if (dy < 0)

{

dx *= -1;

dy *= -1;

swap(x1, x2);

swap(y1, y2);

}

// get the address of the pixel at (x1,y1)

unsigned int* startPixel = &pixels[y1 * pixelStride + x1];

// determine special cases

if (dx > 0)

DrawLineMajorAxis(startPixel, pixelStride, 1, dy, dx, color);

else if (dx < 0)

DrawLineMajorAxis(startPixel, pixelStride, -1, dy, -dx, color);

else

DrawLineSingleAxis(startPixel, pixelStride, dy, color);

}

}

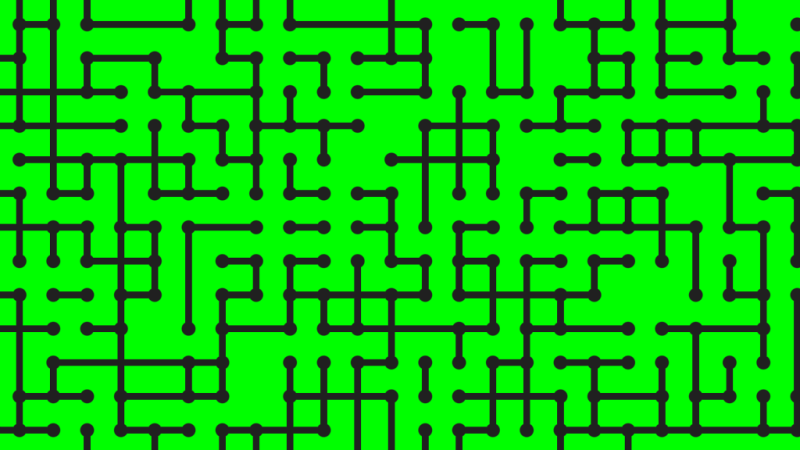

Using the above functions, I wrote a little test to draw lines from the center of an image towards the edges at 100 different angles, and also a horizontal and vertical line. Here’s the results:

Run Slice Algorithm

So, like I said above, there is another Bresenham line algorithm that is a run slice algorithm.

What that means is that instead of looping across the major axis figuring out if each pixel needs to move on the minor axis as well, instead it loops across the minor axis, figuring out how many pixels it needs to write for that row or column of pixels.

One benefit of that algorithm is that it is less loop iterations since it’s looping across the minor axis pixels instead of the major axis.

Here’s an interesting read about Michael Abrash and his encounters with and the run slice algorithm:

Other Bresenham Algorithms

This was origionally just going to be about the line algorithms, and I was going to make up another post about the circle algorithm, but I changed my mind.

While doing some research to see if there was a Bresenham bezier curve algorithm I stumbled on the page below, which shows that yes, there is! There are quite a few other algorithms as well:

Many Bresenham algorithms with very short c++ implementations