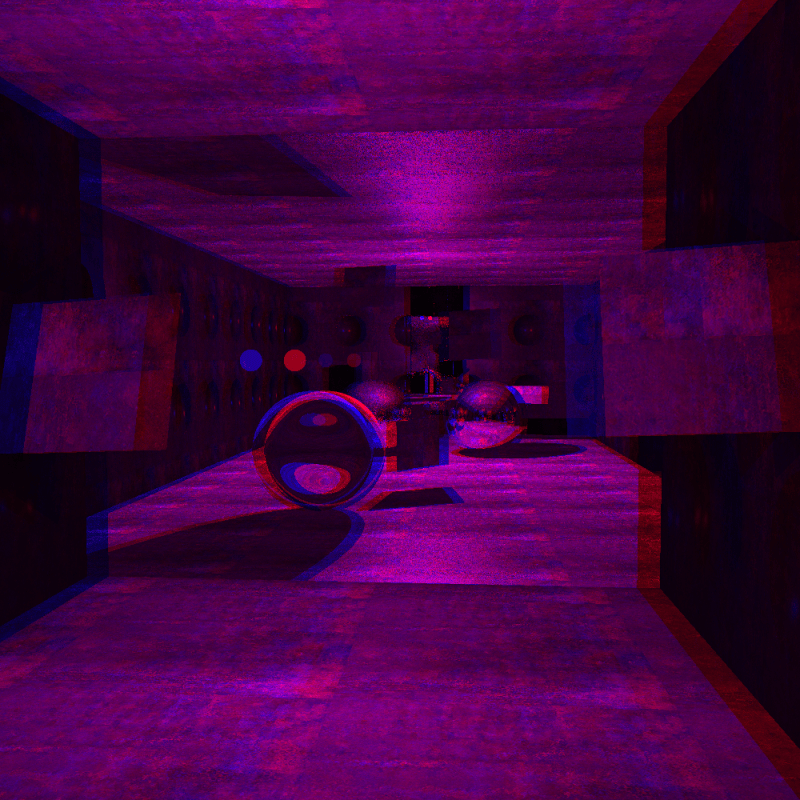

There are a number of ways to implement the effect of fog with modern real time rendered graphics. This blog post will explain how to render fog that has varying density, based on a function of X,Y,Z location in space, like in the picture above.

Faked Fog

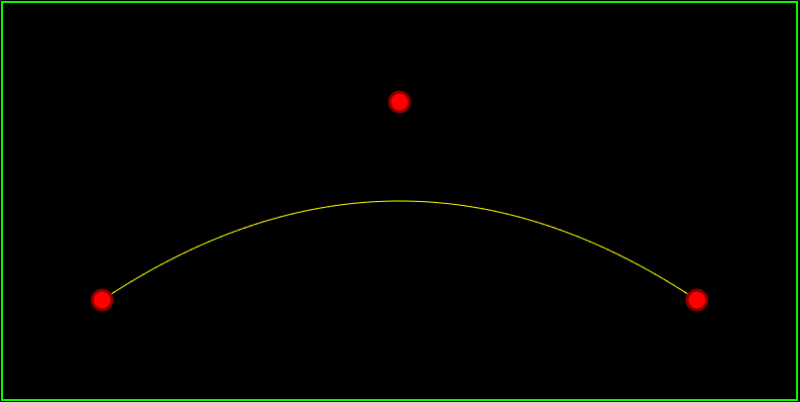

One way is to “fake it” and do something like set the color of a pixel on an object to be based on it’s height. For instance you might say that pixels with a y axis value above 15 are unfogged, pixels with y axis values between 15 and 10 progressively get more fogged as they get closer to 10, and pixels with y axis values less than 10 are completely fogged. That can make some fog that looks like this:

A strange side effect of doing that though, is if you go down “into” the fog, and look out of the fog, things that should be fogged won’t. For instance, looking up at a mountain from inside the fog, the mountain won’t be fogged at all, even though it should be because you are inside of the fog.

A better way to do it, if you intend for the camera to be able to go into the fog, is to calculate a fogging amount for a pixel based on how far away it is from the view point, and how dense the fog is between the view point and the destination point.

If you are doing ray based rendering, like ray tracing or ray marching, you might find yourself trying to find how much fog is between points that don’t involve the view point – like if you are calculating the reflection portion of a ray. In this case, you are just finding out how much fog there is between the point where the reflection happened and the closest intersection. You can consider the point of reflection as the “view point” for the purpose of fogging.

Sometimes, the entire scene might not be in fog. In this case, you have to find where the fog begins and ends, instead of the total distance between the view point and the destination point.

In any case, the first thing you need to do when fogging is figure out the point where the fog begins, and the point where the fog ends. Then, you can figure out how much fog there is based on how the fog density works.

Constant Density Fog

The simplest sort of fog is fog that has the same density all throughout it.

What you do in this case is just multiply the fog density by the distance spent in the fog to come up with a final fog value.

As an example, your fog density might be “0.04” and if you are fogging a pixel 10 units away, you multiply density by distance. FogAmount = 0.04 * 10.0 = 0.4.

Doing this, you know the pixel should be 40% fogged, so you interpolate the pixel’s color 40% towards the fog color. You should make sure to clamp the fog amount to be between 0 and 1 to avoid strange visual anomolies.

The image below shows a constant fog density of 0.04.

Here’s an image of the same constant density fog as viewed from inside the fog:

A problem with constant fog density though, is that if you view it from edge on, you’ll get a very noticeable hard edge where the fog begins, like you can see in the image below:

Linear Density Fog

With linear fog density, the fog gets denser linearly, the farther you go into the fog.

With a fog plane, you can get the density of the fog for a specified point by doing a standard “distance from plane to point” calculation and multiplying that by how much the fog density grows per unit of distance. If your plane is defined by A*x+B*y+C*y+D = 0, and your point is defined as X,Y,Z, you just do a dot product between the plane and the point, giving the point a W component of one.

In other words…

FogDensity(Point, Plane) = (Plane.NormX * Point.X + Plane.NormY * Point.Y + Plane.NormZ * Point.Z + Plane.D * 1.0) * FogGrowthFactor

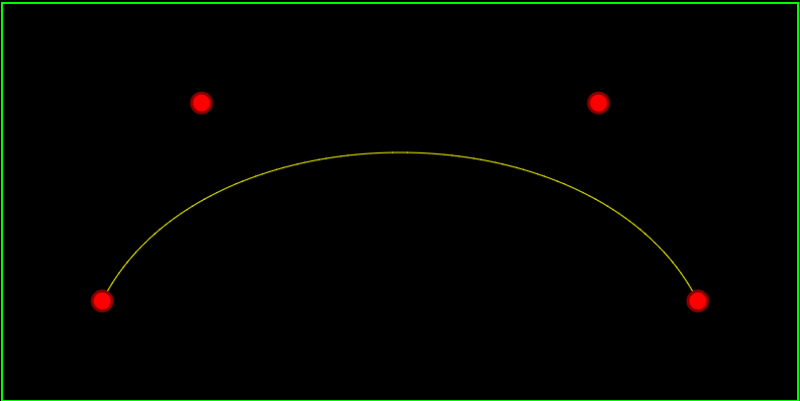

Here’s a picture of linear fog with a fog growth factor of 0.01:

The same fog viewed from the inside:

And lastly, the fog viewed edge on to show that the “hard line” problem of linear fog is gone (dramatic difference isn’t it?!):

Analytic Fog Density – Integrals

Taking a couple steps further, you might want to use equations to define fog density with some function FogDensity = f(x,y,z,).

How could you possibly figure out how much fog there is between two given points when the density between them varies based on some random function?

One way would be to take multiple samples along the line segment between the view point and the destination point, and either calculate the fog amount in each section, or maybe average the densities you calculate and multiply the result by the total distance. You might have to take a lot of samples to make this look correct, causing low frame rate, or accepting low visual quality as a compromise.

If you look at the graphs for the previous fog types, you might notice that we are trying to find the area under the graphs between points A and B. For constant density fog, the shape is a rectangle, so we just multiply width (time in fog) by height (the constant fog density) to get the fog amount. For linear density fog, the shape is a trapezoid, so we use the trapezoid area formula which is height (in this case, the distance in the fog) times the sum of the base lengths (the fog densities at points A and B) divided by 2.

How can we get the area under the graph between A and B for an arbitrary formula though? Well, a way exists luckily, using integrals (thanks to my buddy “Danny The Physicist” for educating me on the basics of integrals!).

There’s a way to transform a formula to get an “indefinite integral”, which itself is also a formula. I won’t go into the details of how to do that, but you can easily get the indefinite integral of a function by typing it into Wolfram Alpha.

Once you have the indefinite integral (let’s call it G(x)) of the fog density formula (let’s call it F(x)), if you calculate G(B) – G(A), that will give you the area under the graph in F(X) between A and B. Yes, seriously, that gives us the area under the graph between our points, thus giving us the amount of fog that exists between the two points for an arbitrary fog density function!

Note that when you plug a value into the indefinite integral and get a number out, that number is called the definite integral.

Analytic Fog Density – Implementation Details

Now that the theory is worked out let’s talk about implementation details.

First off, coming from an additive audio synthesis type of angle, I figured I might have some good luck adding together sine waves of various frequencies and amplitudes, so I started with this:

sin(x*F) * A

F is a frequency multiplier that controls how long the sine wave is. A is an amplitude multiplier that controls how dense the fog gets max.

Next, I knew that I needed a fog density function that never goes below zero, because that would mean if you looked through a patch of negative fog density, it would make the other fog you were looking through be less dense. That is just weird, and doesn’t exist in reality (but maybe there is some interesting visual effect hiding in there somewhere??), so the formula evolved to this, making sure the function never went below zero:

(1 + sin(x*F)) * A

Plugging that equation into wolfram alpha, it says the indefinite integral is:

(x – (cos(x*F)) / F) * A

You can check that out here:

Wolfram Alpha: (1 + sin(x*F)) * A.

It’s also kind of fun to ask google to graph these functions so you can see what they do to help understand how they work. Here are the graphs for A = 0.01 and F = 0.6:

Fog Density: graph (1 + sin(x*0.6)) * 0.01

Indefinite Integral: graph (x – (cos(x*0.6)) / 0.6) * 0.01

So, if you have point A and B where the fogging begins and ends, you might think you can do this to get the right answer:

FogAmount = G(B.x) – G(A.x)

Nope! There’s a catch. That would work if A and B had no difference on the y or z axis, but since they probably do, you need to jump through some hoops. In essence, you need to stretch your answer across the entire length of the line segment between A and B.

To do that, firstly you need to get that fog amount down to unit length. You do that by modifying the formula like so:

FogAmount = (G(B.x) – G(A.x)) / (B.x – A.x)

This also has a secondary benefit of making it so that your fog amount is always positive (so long as your fog density formula F(X) can’t ever go negative!), which saves an abs() call. Making it always positive ensures that this works when viewing fog both from the left and the right.

Now that we have the fog amount down to unit length, we need to scale it to be the length of the line segment, which makes the formula into this:

FogAmount = (G(B.x) – G(A.x)) * Length(B-A)/(B.x – A.x)

That formula will now give you the correct fog amount.

But, one axis of fog wasn’t enough to look very good, so I wanted to make sure and do one sine wave on each axis. I used 0.01 amplitude for each axis, but for the X axis i used a frequency of 0.6, for the Y axis i used a frequency of 1.2 and for the Z axis i used a frequency of 0.9.

Also, I wanted to give a little bit of baseline fog, so I added some constant density fog in as well, with a constant density of 0.1.

As a bonus, I also gave each axis a “movement factor” that made the sine waves move over time. X axis had a factor of 2.0, Y axis had a factor of 1.4 and Z axis had a factor of 2.2.

Putting all of this together, here is the final fog equation (GLSL pixel shader code) for finding the fog amount between any two points at a specific point in time:

//=======================================================================================

float DefiniteIntegral (in float x, in float amplitude, in float frequency, in float motionFactor)

{

// Fog density on an axis:

// (1 + sin(x*F)) * A

//

// indefinite integral:

// (x - cos(F * x)/F) * A

//

// ... plus a constant (but when subtracting, the constant disappears)

//

x += iGlobalTime * motionFactor;

return (x - cos(frequency * x)/ frequency) * amplitude;

}

//=======================================================================================

float AreaUnderCurveUnitLength (in float a, in float b, in float amplitude, in float frequency, in float motionFactor)

{

// we calculate the definite integral at a and b and get the area under the curve

// but we are only doing it on one axis, so the "width" of our area bounding shape is

// not correct. So, we divide it by the length from a to b so that the area is as

// if the length is 1 (normalized... also this has the effect of making sure it's positive

// so it works from left OR right viewing). The caller can then multiply the shape

// by the actual length of the ray in the fog to "stretch" it across the ray like it

// really is.

return (DefiniteIntegral(a, amplitude, frequency, motionFactor) - DefiniteIntegral(b, amplitude, frequency, motionFactor)) / (a - b);

}

//=======================================================================================

float FogAmount (in vec3 src, in vec3 dest)

{

float len = length(dest - src);

// calculate base fog amount (constant density over distance)

float amount = len * 0.1;

// calculate definite integrals across axes to get moving fog adjustments

float adjust = 0.0;

adjust += AreaUnderCurveUnitLength(dest.x, src.x, 0.01, 0.6, 2.0);

adjust += AreaUnderCurveUnitLength(dest.y, src.y, 0.01, 1.2, 1.4);

adjust += AreaUnderCurveUnitLength(dest.z, src.z, 0.01, 0.9, 2.2);

adjust *= len;

// make sure and not go over 1 for fog amount!

return min(amount+adjust, 1.0);

}

More Info

I ended up only using one sine wave per axis, but I think with more sine waves, or perhaps different functions entirely, you could get some more convincing looking fog.

At some point in the future, I’d like to play around with exponential fog density (instead of linear) where the exponential power is a parameter.

I also think that maybe squaring the sine waves could make them have sharper density changes perhaps…

One thing that bugs me in the above screenshots is the obvious “hard line” in both constant and linear fog where it seems fog crosses a threshold and gets a lot denser. I’m not really sure how to fix that yet. In traditional rasterized graphics you could put the fog amount on a curve, to give it a smoother transition, but in ray based rendering, that could make things a bit odd – like you could end up with an exponential curve butting up against the start of a different exponential curve (due to reflection or refraction or similar). The fog density would end up looking like log graph paper which would probably not look so great – although honestly I haven’t tried it to see yet!

If you have any questions, or feedback about improvements you know about or have discovered in any of the above, post a comment and let me know!

Here’s a good read on fog defined by a plane, that also gets into how to make branchless calculations for the fog amounts.

Unified Distance Formulas for Halfspace Fog

Interactive ShaderToy.com demo with GLSL pixel shader source code that you can also edit in real time with WebGL: