Count min sketch is a probabilistic histogram that was invented in 2003 by Graham Cormode and S. Muthukrishnan.

It’s a histogram in that it can store objects (keys) and associated counts.

It’s probabilistic in that it lets you trade space and computation time for accuracy.

The count min sketch is pretty similar to a bloom filter, except that instead of storing a single bit to say whether an object is in the set, the count min sketch allows you to keep a count per object. You can read more about bloom filters here: Estimating Set Membership With a Bloom Filter.

It’s called a “sketch” because it’s a smaller summarization of a larger data set.

Inserting an Item

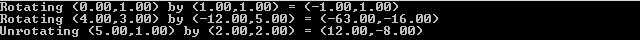

The count min sketch is just a 2 dimensional array, with size of W x D. The actual data type in the array depends on how much storage space you want. It could be an unsigned char, it could be 4 bits, or it could be a uint64 (or larger!).

Each row (value of D) uses a different hash function to map objects to an index of W.

To insert an object, for each row you hash the object using that row’s hash function to get the W index for that object, then increment the count at that position.

In this blog post, I’m only going to be talking about being able to add items to the count min sketch. There are different rules / probabilities / etc for count min sketches that can have objects removed, but you can check out the links at the bottom of this post for more information about that!

Getting an Item Count

When you want to get the count of how many times an item has been added to the count min sketch, you do a similar operation as when you insert.

For each row, you hash the object being asked about with that row’s hash function to get the W index and then get the value for that row at the W index.

This will give you D values and you just return the smallest one.

The reason for this, is because due to hash collisions of various hash functions, your count in a specific slot may have been incorrectly incremented extra times due to other objects hashing to the same object. If you take the minimum value you’ve seen across all rows, you are guaranteed to be taking the value that has the least number of hash collisions, so is guaranteed to be most correct, and in fact guaranteed to be greater than or equal to the actual answer – but never lower than the actual answer.

Dot Product (Inner Product)

If you read the last post on using dot product with histograms to gauge similarity, you might be wondering if you can do a dot product between two count min sketch objects.

Luckily yes, you can! They need to have the same W x D dimensions and they need to use the same hash functions per row, but if that’s true, you can calculate a dot product value very easily.

If you have two count min sketch objects A and B that you want to calculate the dot product for, you dot product each row (D index) of the two count min sketch objects. This will leave you with D dot products and you just return the smallest one. This guarantees that the dot product value you calculate will have the fewest hash collisions (so will be most accurate), and will also guarantee that the estimate is greater that or equal to the actual answer, but will never be lower.

To Normalize Or Not To Normalize

There is a caveat here though with doing a dot product between two count min sketch objects. If you do a normalized dot product (normalize the vectors before doing a dot product, or dividing the answer by the length of the two vectors multiplied together), the guarantee that the dot product is greater than or equal to the true answer no longer holds!

The reason for this is that the formula for doing a normalized dot product is like this:

normalized dot product = dot(A,B) / (length(A)*length(B))

In a count min sketch, the dot(A,B) estimate is guaranteed to greater than or equal to the true value.

The length of a vector is also guaranteed to be greater than or equal to the length of the true vector (the vector made from the actual histogram values).

This means that the numerator and the denominator BOTH have varying levels of overestimation in them. Overestimation in the numerator makes the normalized dot product estimate larger, while overestimation in the denominator makes the normalized dot product estimate smaller.

The result is that a normalized dot product estimate can make no guarantee about being greater than or equal to the true value!

This may or may not be a problem for your situation. Doing a dot product with unnormalized vectors still gives you a value that you can use to compare “similarity values” between histograms, but it has slightly different meaning than a dot product with normalized vectors.

Specifically, if the counts are much larger in one histogram versus another (such as when doing a dot product between multiple large text documents and a small search term string), the “weight” of the larger counts will count for more.

That means if you search for “apple pie”, a 100 page novel that mentions apples 10 times will be a better match than a 1/2 page recipe for apple pie!

When you normalize histograms, it makes it so the counts are “by percentage of the total document length”, which would help our search correctly find that the apple pie recipe is more relevant.

In other situations, you might want to let the higher count weigh stronger even though the occurrences are “less dense” in the document.

It really just depends on what your usage case is.

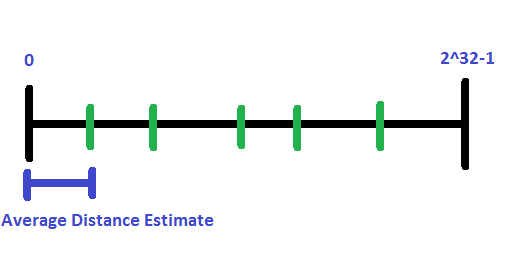

Calculating W & D

There are two parameters (values) used when calculating the correct W and D dimensions of a count min sketch, for the desired accuracy levels. The parameters are ε (epsilon) and δ (delta).

ε (Epsilon) is “how much error is added to our counts with each item we add to the cm sketch”.

δ (Delta) is “with what probability do we want to allow the count estimate to be outside of our epsilon error rate”

To calculate W and D, you use these formulas:

W = ⌈e/ε⌉

D = ⌈ln (1/δ)⌉

Where ln is “natural log” and e is “euler’s constant”.

Accuracy Guarantees

When querying to get a count for a specific object (also called a “point query”) the accuracy guarantees are:

- True Count <= Estimated Count

- Estimated Count <= True Count + ε * Number Of Items Added

- There is a δ chance that #2 is not true

When doing an unnormalized dot product, the accuracy guarantees are:

- True Dot Product <= Estimated Dot Product

- Estimated Dot Product <= True Dot Product + ε * Number Of Items Added To A * Number Of Items Added To B

- There is a δ chance that #2 is not true

Conservative Update

There is an alternate way to implement adding an item to the cm sketch, which results in provably less error. That technique is called a “Conservative Update”.

When doing a conservative update, you first look at the values in each row that you would normally increment and keep track of the smallest value that you’ve seen. You then only increment the counters that have that smallest value.

The reason this works is because we only look at the smallest value across all rows when doing a look up. So long as the smallest value across all rows increases when you insert an object, you’ve satisfied the requirements to make a look up return a value that is greater than or equal to the true value. The reason this conservative update results in less error is because you are writing to fewer values, which means that there are fewer hash collisions happening.

While this increases accuracy, it comes at the cost of extra logic and processing time needed when doing an update, which may or may not be appropriate for your needs.

Example Runs

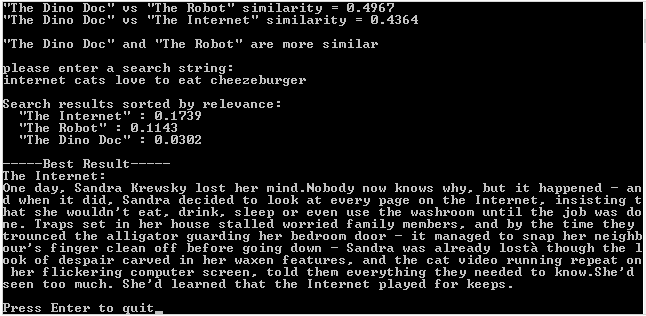

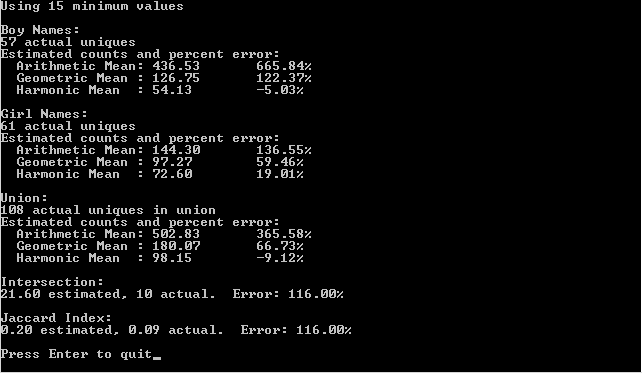

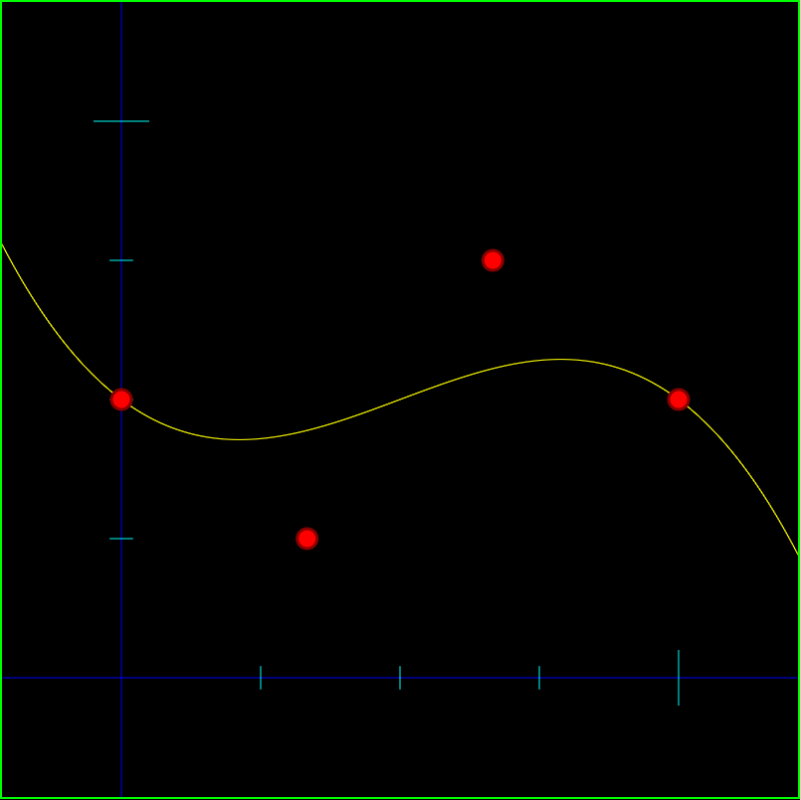

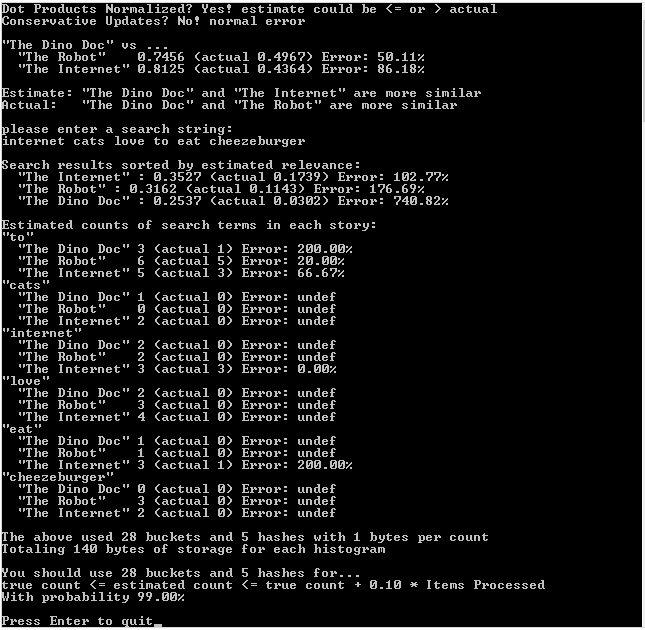

The example program is a lot like the program from the last post which implemented some search engine type functionality.

This program also shows you some count estimations to show you that functionality as well.

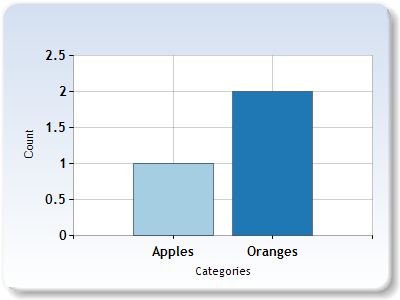

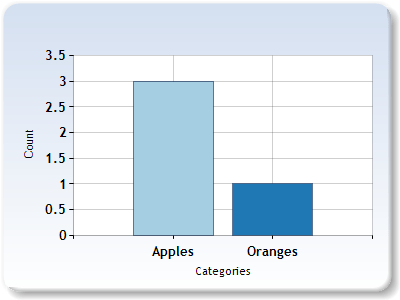

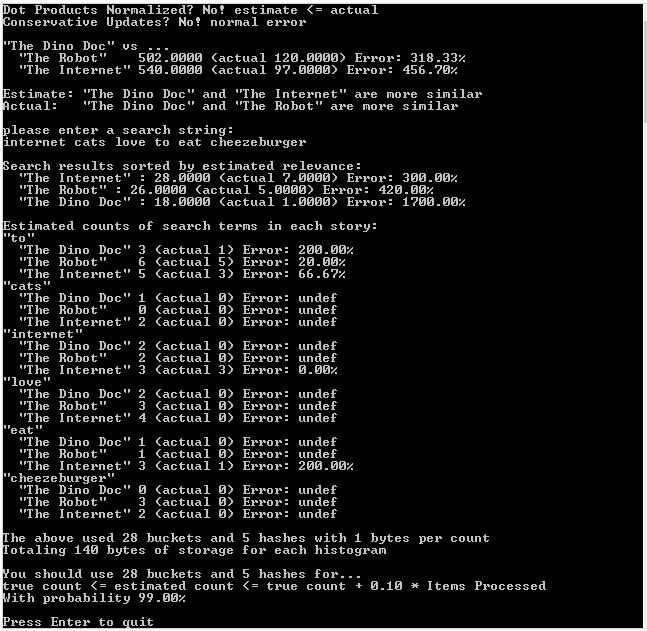

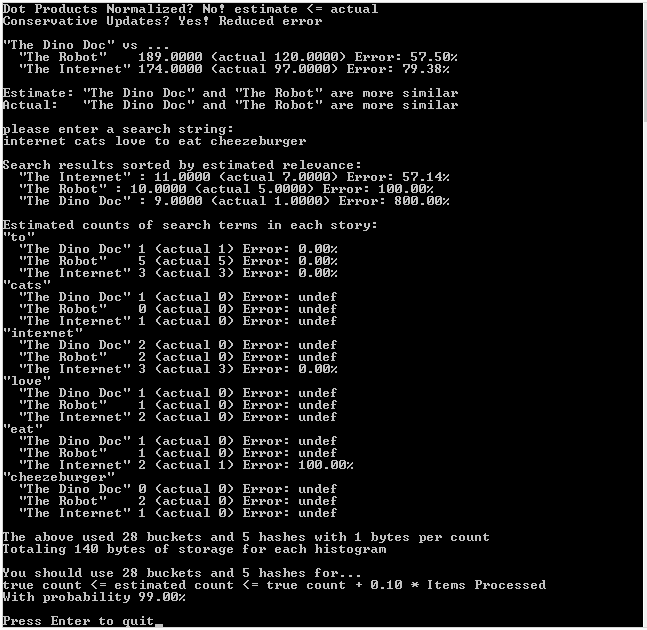

The first run of the program is with normalized vectors, the second run of the program is with unnormalized vectors, and the third run of the program, which is most accurate, is with unnormalized vectors and conservative updates.

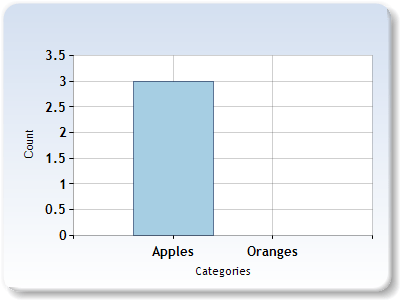

First Run: Normalized Vectors, Regular Updates

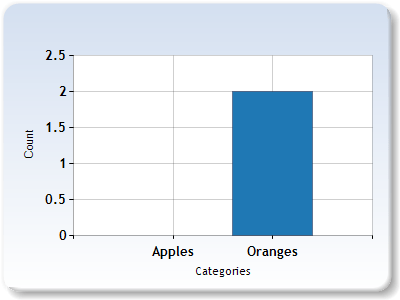

Second Run: Unnormalized Vectors, Regular Updates

Third Run: Unnormalized Vectors, Conservative Updates

Example Code

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

const float c_eulerConstant = (float)std::exp(1.0);

// The CCountMinSketch class

template <typename TKEY, typename TCOUNTTYPE, unsigned int NUMBUCKETS, unsigned int NUMHASHES, typename HASHER = std::hash>

class CCountMinSketch

{

public:

typedef CCountMinSketch TType;

CCountMinSketch ()

: m_countGrid { } // init counts to zero

, m_vectorLengthsDirty(true)

{ }

static const unsigned int c_numBuckets = NUMBUCKETS;

static const unsigned int c_numHashes = NUMHASHES;

typedef TCOUNTTYPE TCountType;

void AddItem (bool conservativeUpdate, const TKEY& item, const TCOUNTTYPE& count)

{

// this count min sketch is only supporting positive counts

if (count = 0!n");

return;

}

// remember that our vector lengths are inaccurate

m_vectorLengthsDirty = true;

// if doing a conservative update, only update the buckets that are necesary

if (conservativeUpdate)

{

// find what the lowest valued bucket is and calculate what our new lowest

// value should be

TCOUNTTYPE lowestValue = GetCount(item) + count;

// make sure every bucket has at least the lowest value it should have

size_t rawHash = HASHER()(item);

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < NUMHASHES; ++i)

{

size_t hash = std::hash()(rawHash ^ std::hash()(i));

TCOUNTTYPE value = m_countGrid[i][hash%NUMBUCKETS];

if (value < lowestValue)

m_countGrid[i][hash%NUMBUCKETS] = lowestValue;

}

}

// else do a normal update

else

{

// for each hash, find what bucket this item belongs in, and add the count to that bucket

size_t rawHash = HASHER()(item);

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < NUMHASHES; ++i)

{

size_t hash = std::hash()(rawHash ^ std::hash()(i));

m_countGrid[i][hash%NUMBUCKETS] += count;

}

}

}

TCOUNTTYPE GetCount (const TKEY& item)

{

// for each hash, get the value for this item, and return the smalles value seen

TCOUNTTYPE ret = 0;

size_t rawHash = HASHER()(item);

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < NUMHASHES; ++i)

{

size_t hash = std::hash()(rawHash ^ std::hash()(i));

if (i == 0 || ret > m_countGrid[i][hash%NUMBUCKETS])

ret = m_countGrid[i][hash%NUMBUCKETS];

}

return ret;

}

void CalculateVectorLengths ()

{

// if our vector lengths were previously calculated, no need to do anything

if (!m_vectorLengthsDirty)

return;

// calculate vector lengths of each hash

for (unsigned int hash = 0; hash < NUMHASHES; ++hash)

{

m_vectorLengths[hash] = 0.0f;

for (unsigned int bucket = 0; bucket < NUMBUCKETS; ++bucket)

m_vectorLengths[hash] += (float)m_countGrid[hash][bucket] * (float)m_countGrid[hash][bucket];

m_vectorLengths[hash] = sqrt(m_vectorLengths[hash]);

}

// remember that our vector lengths have been calculated

m_vectorLengthsDirty = false;

}

friend float HistogramDotProduct (TType& A, TType& B, bool normalize)

{

// make sure the vector lengths are accurate. No cost if they were previously calculated

A.CalculateVectorLengths();

B.CalculateVectorLengths();

// whatever hash has the smallest dot product is the most correct

float ret = 0.0f;

bool foundValidDP = false;

for (unsigned int hash = 0; hash < NUMHASHES; ++hash)

{

// if either vector length is zero, don't consider this dot product a valid result

// we cant normalize it, and it will be zero anyways

if (A.m_vectorLengths[hash] == 0.0f || B.m_vectorLengths[hash] == 0.0f)

continue;

// calculate dot product of unnormalized vectors

float dp = 0.0f;

for (unsigned int bucket = 0; bucket dp)

{

ret = dp;

foundValidDP = true;

}

}

return ret;

}

private:

typedef std::array TBucketList;

typedef std::array TTable;

TTable m_countGrid;

bool m_vectorLengthsDirty;

std::array m_vectorLengths;

};

// Calculate ideal count min sketch parameters for your needs.

unsigned int CMSIdealNumBuckets (float error)

{

return (unsigned int)std::ceil((float)(c_eulerConstant / error));

}

unsigned int CMSIdealNumHashes (float probability)

{

return (unsigned int)std::ceil(log(1.0f / probability));

}

typedef std::string TKeyType;

typedef unsigned char TCountType;

typedef CCountMinSketch THistogramEstimate;

typedef std::unordered_map THistogramActual;

// These one paragraph stories are from http://birdisabsurd.blogspot.com/p/one-paragraph-stories.html

// The Dino Doc : http://birdisabsurd.blogspot.com/2011/11/dino-doc.html (97 words)

const char *g_storyA =

"The Dino Doc:n"

"Everything had gone according to plan, up 'til this moment. His design team "

"had done their job flawlessly, and the machine, still thrumming behind him, "

"a thing of another age, was settled on a bed of prehistoric moss. They'd "

"done it. But now, beyond the protection of the pod and facing an enormous "

"tyrannosaurus rex with dripping jaws, Professor Cho reflected that, had he "

"known of the dinosaur's presence, he wouldn't have left the Chronoculator - "

"and he certainly wouldn't have chosen "Stayin' Alive", by The Beegees, as "

"his dying soundtrack. Curse his MP3 player";

// The Robot: http://birdisabsurd.blogspot.com/2011/12/robot.html (121 words)

const char *g_storyB =

"The Robot:n"

"The engineer watched his robot working, admiring its sense of purpose.It knew "

"what it was, and what it had to do.It was designed to lift crates at one end "

"of the warehouse and take them to the opposite end.It would always do this, "

"never once complaining about its place in the world.It would never have to "

"agonize over its identity, never spend empty nights wondering if it had been "

"justified dropping a promising and soul - fulfilling music career just to "

"collect a bigger paycheck.And, watching his robot, the engineer decided that "

"the next big revolution in the robotics industry would be programming "

"automatons with a capacity for self - doubt.The engineer needed some company.";

// The Internet: http://birdisabsurd.blogspot.com/2011/11/internet.html (127 words)

const char *g_storyC =

"The Internet:n"

"One day, Sandra Krewsky lost her mind.Nobody now knows why, but it happened - "

"and when it did, Sandra decided to look at every page on the Internet, "

"insisting that she wouldn't eat, drink, sleep or even use the washroom until "

"the job was done. Traps set in her house stalled worried family members, and by "

"the time they trounced the alligator guarding her bedroom door - it managed to "

"snap her neighbour's finger clean off before going down - Sandra was already "

"lost… though the look of despair carved in her waxen features, and the cat "

"video running repeat on her flickering computer screen, told them everything "

"they needed to know.She'd seen too much. She'd learned that the Internet "

"played for keeps.";

void WaitForEnter ()

{

printf("nPress Enter to quit");

fflush(stdin);

getchar();

}

template

void ForEachWord (const std::string &source, L& lambda)

{

size_t prev = 0;

size_t next = 0;

while ((next = source.find_first_of(" ,.-":n", prev)) != std::string::npos)

{

if ((next - prev != 0))

{

std::string word = source.substr(prev, next - prev);

std::transform(word.begin(), word.end(), word.begin(), ::tolower);

lambda(word);

}

prev = next + 1;

}

if (prev < source.size())

{

std::string word = source.substr(prev);

std::transform(word.begin(), word.end(), word.begin(), ::tolower);

lambda(word);

}

}

void PopulateHistogram (THistogramEstimate &histogram, const char *text, bool conservativeUpdate)

{

ForEachWord(text, [&](const std::string &word) {

histogram.AddItem(conservativeUpdate, word, 1);

});

}

void PopulateHistogram (THistogramActual &histogram, const char *text)

{

ForEachWord(text, [&histogram](const std::string &word) {

histogram[word]++;

});

}

float HistogramDotProduct (THistogramActual &A, THistogramActual &B, bool normalize)

{

// Get all the unique keys from both histograms

std::set keysUnion;

std::for_each(A.cbegin(), A.cend(), [&keysUnion](const std::pair& v)

{

keysUnion.insert(v.first);

});

std::for_each(B.cbegin(), B.cend(), [&keysUnion](const std::pair& v)

{

keysUnion.insert(v.first);

});

// calculate and return the normalized dot product!

float dotProduct = 0.0f;

float lengthA = 0.0f;

float lengthB = 0.0f;

std::for_each(keysUnion.cbegin(), keysUnion.cend(),

[&A, &B, &dotProduct, &lengthA, &lengthB]

(const TKeyType& key)

{

// if the key isn't found in either histogram ignore it, since it will be 0 * x which is

// always anyhow. Make sure and keep track of vector length though!

auto a = A.find(key);

auto b = B.find(key);

if (a != A.end())

lengthA += (float)(*a).second * (float)(*a).second;

if (b != B.end())

lengthB += (float)(*b).second * (float)(*b).second;

if (a == A.end())

return;

if (b == B.end())

return;

// calculate dot product

dotProduct += ((float)(*a).second * (float)(*b).second);

}

);

// if we don't need to normalize, return the unnormalized value we have right now

if (!normalize)

return dotProduct;

// normalize if we can

if (lengthA * lengthB <= 0.0f)

return 0.0f;

lengthA = sqrt(lengthA);

lengthB = sqrt(lengthB);

return dotProduct / (lengthA * lengthB);

}

template

const char *CalculateError (const T&estimate, const T&actual)

{

float error = 100.0f * ((float)estimate - (float)actual) / (float)actual;

if (std::isnan(error) || std::isinf(error))

return "undef";

// bad practice to return a static local string, dont do this in production code!

static char ret[256];

sprintf(ret, "%0.2f%%", error);

return ret;

}

int main (int argc, char **argv)

{

// settings

const bool c_normalizeDotProducts = false;

const bool c_conservativeUpdate = true;

// show settings and implication

printf("Dot Products Normalized? %sn",

c_normalizeDotProducts

? "Yes! estimate could be actual"

: "No! estimate <= actual");

printf("Conservative Updates? %snn",

c_conservativeUpdate

? "Yes! Reduced error"

: "No! normal error");

// populate our probabilistic histograms.

// Allocate memory for the objects so that we don't bust the stack for large histogram sizes!

std::unique_ptr TheDinoDocEstimate = std::make_unique();

std::unique_ptr TheRobotEstimate = std::make_unique();

std::unique_ptr TheInternetEstimate = std::make_unique();

PopulateHistogram(*TheDinoDocEstimate, g_storyA, c_conservativeUpdate);

PopulateHistogram(*TheRobotEstimate, g_storyB, c_conservativeUpdate);

PopulateHistogram(*TheInternetEstimate, g_storyC, c_conservativeUpdate);

// populate our actual count histograms for comparison

THistogramActual TheDinoDocActual;

THistogramActual TheRobotActual;

THistogramActual TheInternetActual;

PopulateHistogram(TheDinoDocActual, g_storyA);

PopulateHistogram(TheRobotActual, g_storyB);

PopulateHistogram(TheInternetActual, g_storyC);

// report whether B or C is a closer match for A

float dpABEstimate = HistogramDotProduct(*TheDinoDocEstimate, *TheRobotEstimate, c_normalizeDotProducts);

float dpACEstimate = HistogramDotProduct(*TheDinoDocEstimate, *TheInternetEstimate, c_normalizeDotProducts);

float dpABActual = HistogramDotProduct(TheDinoDocActual, TheRobotActual, c_normalizeDotProducts);

float dpACActual = HistogramDotProduct(TheDinoDocActual, TheInternetActual, c_normalizeDotProducts);

printf(""The Dino Doc" vs ...n");

printf(" "The Robot" %0.4f (actual %0.4f) Error: %sn", dpABEstimate, dpABActual, CalculateError(dpABEstimate, dpABActual));

printf(" "The Internet" %0.4f (actual %0.4f) Error: %snn", dpACEstimate, dpACActual, CalculateError(dpACEstimate, dpACActual));

if (dpABEstimate > dpACEstimate)

printf("Estimate: "The Dino Doc" and "The Robot" are more similarn");

else

printf("Estimate: "The Dino Doc" and "The Internet" are more similarn");

if (dpABActual > dpACActual)

printf("Actual: "The Dino Doc" and "The Robot" are more similarn");

else

printf("Actual: "The Dino Doc" and "The Internet" are more similarn");

// let the user do a search engine style query for our stories!

char searchString[1024];

printf("nplease enter a search string:n");

searchString[0] = 0;

scanf("%[^n]", searchString);

struct SSearchResults

{

SSearchResults(const std::string& pageName, float rankingEstimated, float rankingActual)

: m_pageName(pageName)

, m_rankingEstimated(rankingEstimated)

, m_rankingActual(rankingActual)

{ }

bool operator other.m_rankingEstimated;

}

std::string m_pageName;

float m_rankingEstimated;

float m_rankingActual;

};

std::vector results;

// preform our search and gather our results!

std::unique_ptr searchEstimate = std::make_unique();

THistogramActual searchActual;

PopulateHistogram(*searchEstimate, searchString, c_conservativeUpdate);

PopulateHistogram(searchActual, searchString);

results.push_back(

SSearchResults(

"The Dino Doc",

HistogramDotProduct(*TheDinoDocEstimate, *searchEstimate, c_normalizeDotProducts),

HistogramDotProduct(TheDinoDocActual, searchActual, c_normalizeDotProducts)

)

);

results.push_back(

SSearchResults(

"The Robot",

HistogramDotProduct(*TheRobotEstimate, *searchEstimate, c_normalizeDotProducts),

HistogramDotProduct(TheRobotActual, searchActual, c_normalizeDotProducts)

)

);

results.push_back(

SSearchResults(

"The Internet",

HistogramDotProduct(*TheInternetEstimate, *searchEstimate, c_normalizeDotProducts),

HistogramDotProduct(TheInternetActual, searchActual, c_normalizeDotProducts)

)

);

std::sort(results.begin(), results.end());

// show the search results

printf("nSearch results sorted by estimated relevance:n");

std::for_each(results.begin(), results.end(), [](const SSearchResults& result) {

printf(" "%s" : %0.4f (actual %0.4f) Error: %sn",

result.m_pageName.c_str(),

result.m_rankingEstimated,

result.m_rankingActual,

CalculateError(result.m_rankingEstimated, result.m_rankingActual)

);

});

// show counts of search terms in each story (estimated and actual)

printf("nEstimated counts of search terms in each story:n");

std::for_each(searchActual.cbegin(), searchActual.cend(), [&] (const std::pair& v)

{

// show key

printf(""%s"n", v.first.c_str());

// the dino doc

TCountType estimate = TheDinoDocEstimate->GetCount(v.first.c_str());

TCountType actual = 0;

auto it = TheDinoDocActual.find(v.first.c_str());

if (it != TheDinoDocActual.end())

actual = it->second;

printf(" "The Dino Doc" %u (actual %u) Error: %sn", estimate, actual, CalculateError(estimate, actual));

// the robot

estimate = TheRobotEstimate->GetCount(v.first.c_str());

actual = 0;

it = TheRobotActual.find(v.first.c_str());

if (it != TheRobotActual.end())

actual = it->second;

printf(" "The Robot" %u (actual %u) Error: %sn", estimate, actual, CalculateError(estimate, actual));

// the internet

estimate = TheInternetEstimate->GetCount(v.first.c_str());

actual = 0;

it = TheInternetActual.find(v.first.c_str());

if (it != TheInternetActual.end())

actual = it->second;

printf(" "The Internet" %u (actual %u) Error: %sn", estimate, actual, CalculateError(estimate, actual));

});

// show memory use

printf("nThe above used %u buckets and %u hashes with %u bytes per countn",

THistogramEstimate::c_numBuckets, THistogramEstimate::c_numHashes, sizeof(THistogramEstimate::TCountType));

printf("Totaling %u bytes of storage for each histogramnn",

THistogramEstimate::c_numBuckets * THistogramEstimate::c_numHashes * sizeof(THistogramEstimate::TCountType));

// show a probabilistic suggestion

float error = 0.1f;

float probability = 0.01f;

printf("You should use %u buckets and %u hashes for...n", CMSIdealNumBuckets(error), CMSIdealNumHashes(probability));

printf("true count <= estimated count <= true count + %0.2f * Items ProcessednWith probability %0.2f%%n", error, (1.0f - probability)*100.0f);

WaitForEnter();

return 0;

}

Links

If you use this in production code, you should probably use a better quality hash.

The rabbit hole on this stuff goes deeper, so if you want to know more, check out these links!

Wikipedia: Count Min Sketch

Count Min Sketch Full Paper

Count Min Sketch AT&T Research Paper

Another CMS paper

And another, with some more info like range query details

Next up I’ll be writing about hyperloglog, which does the same thing as KMV (K-Minimum Values) but is better at it!