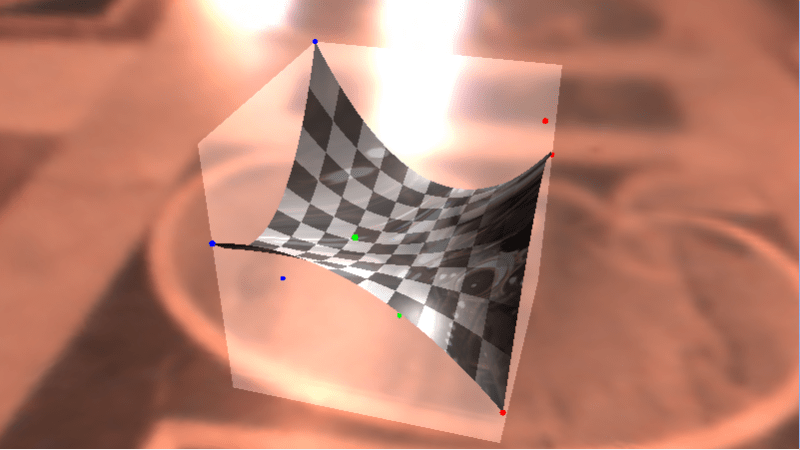

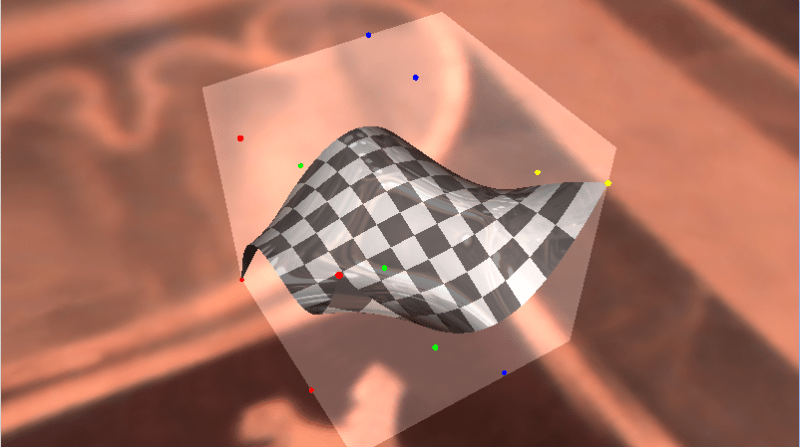

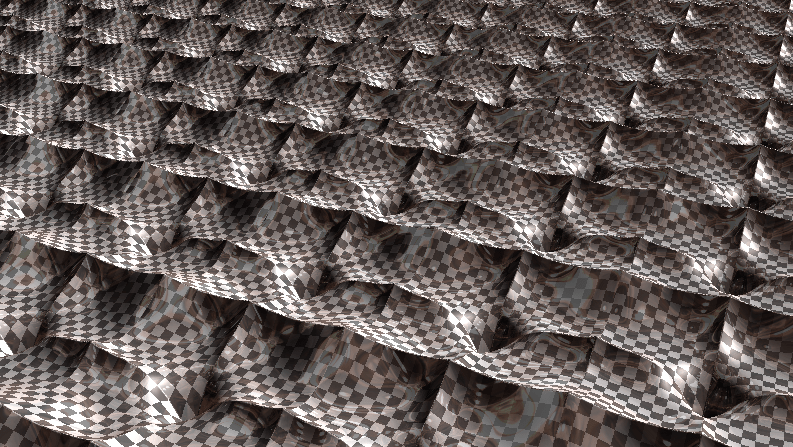

Rectangular Bezier Patches are one way to bring Bezier curves into the 3rd dimension as a Bezier surface. Below is a rendered image of a quadratic Bezier rectangle (degree of (2,2)) and a cubic Bezier rectangle (degree of (3,3)) taken as screenshots from a shadertoy demo I created that renders these in real time. Links at bottom of post!

Intuition

Imagine that you had a Bezier curve with some number of control points. Now, imagine that you wanted to animate those control points over time instead of having a static curve.

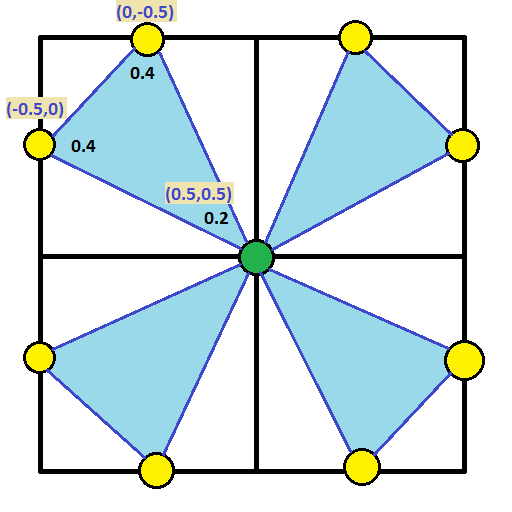

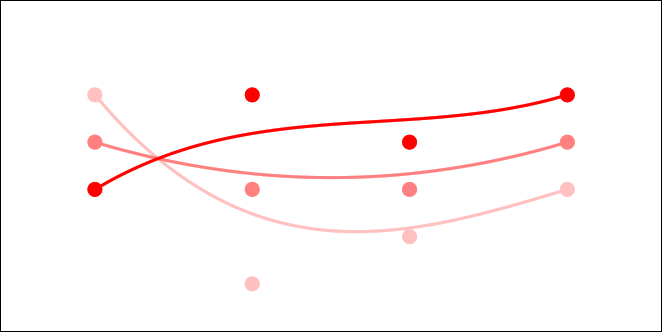

One way to do this would be to just have multiple sets of control points as key frames, and just linearly interpolate between the key frames over time. You’d get something that might look like the image below (lighter red = farther back in time).

That is a simple and intuitive way to animate a Bezier curve, and is probably what you thought of immediately. Interestingly though, since linear interpolation is really a degree 1 Bezier curve, this method is actually using a degree 1 Bezier curve to control each control point!

What if we tried a higher order curve to animate each control point? Well… we could have three sets of control points, so that each control point was controlled over time by a quadratic curve. We could also try having four sets of control points, so that each control point was controlled over time by a cubic curve.

We could have any number of sets of control points, to be able to animate the control points over time using any degree curve.

Now, instead of animating the curve over TIME, what if we controlled it over DISTANCE (like, say, the z-axis, or “depth”). Look at the image above and think of it like you are looking at a surface from the side. If you took a bunch of the time interpolations as slices and set them next to each other so that there were no gaps between them, you’d end up with a smooth surface. TA-DA! This is how a Rectangular Bezier Patch is made.

Note that the degree of the curve on one axis doesn’t have to match the degree of the curve on the other axis. You could have a cubic curve where each control point is controlled by a linear interpolation, or you could have a degree 5 curve where each control point is controlled by degree 7 curves. Since there are two degrees involved in a Bezier rectangle, you describe it’s order with two numbers. The first example is degree (3,1) and the second example is degree (5,7).

Higher Dimensions

While you thinking about this, I wanted to mention that you could animate a bezier rectangle over time, using bezier curves to control those control points. If you then laid that out over distance instead of time, you’d end up with a rectangular box Bezier solid. If you are having trouble visualizing that, don’t feel dumb, it’s actually four dimensional!

You can think of it like a box that has a value stored at every (x,y,z) location, and those values are controlled by Bezier formulas so are smooth and are based on control points. It’s kind of a strange concept but is useful in some situations.

Say you made a 3d hot air baloon game and wanted to model temperature of the air at differently locations to simulate thermals. One way you could do this would be to store a bunch of temperatures in a 3d grid. Another way might involve using a grid of rectangular box Bezier solids perhaps. One benefit to the Bezier solid representation is that the data points are much smoother than a grid would be, and another is that you could make the grid much less dense.

Now, let’s say that you wanted to animate the thermals over time. You could use a fifth dimensional bezier hypercube solid. Let’s move on, my brain hurts 😛

Math

The equation for a Bezier Rectangle is:

is the point on the surface that you get after you plug in the parameters.

and

are the parameters to the surface and should be within the range 0 to 1. These are the same thing as the

you see in Bezier curves, but there are two of them since there are two axes.

There are two Sigmas (summations) which mean that it’s a double for loop.

One of the for loops make go from 0 to

and the other makes

go from 0 to

.

and

are the degree of each axis.

and

are Bernstein polynomials (aka binomial expansion terms) just as you see in Bezier Curves – there is just one per axis.

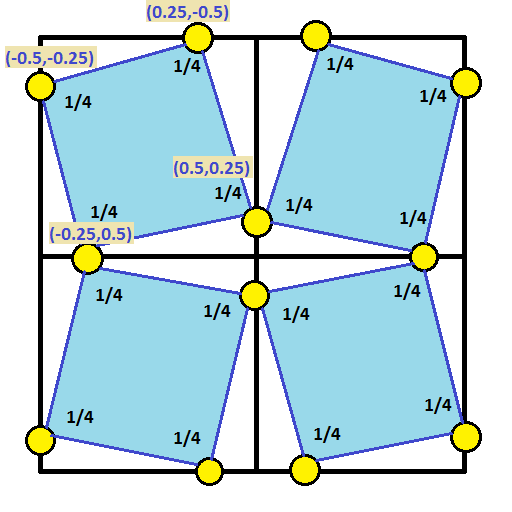

Lastly comes the control points . The number of control on one axis are multiplied by the number of control points on the other axis.

A biquadratic Bezier patch has a degree of (2,2) and has 3 control points on one axis, and 3 control points on the other. That means that it has 9 control points total.

A bicubic Bezier patch has a degree of (3,3) with 4 control points on each axis, for a total of 16 control points.

If you had a patch of degree (7,1), it would have 8 control points on one axis and 2 control points on the other axis, and so would also have 16 control points total, but they would be laid out differently than a bicubic Bezier patch.

As far as actually calculating points on a curve, the above only calculates the value for a single axis for the final point on the curve. If you have three dimensional control points (X,Y,Z), you have to do the above math for each one to get the final result. This is the same as how it works for evaluating Bezier curves.

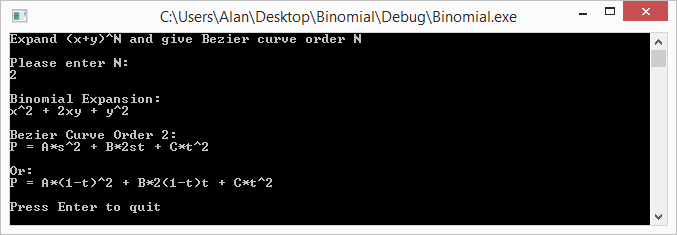

Code

#include

#include

typedef std::array TFloat3;

typedef std::array TFloat3x3;

const TFloat3x3 c_ControlPointsX =

{

{

{ 0.7f, 0.8f, 0.9f },

{ 0.2f, 0.5f, 0.4f },

{ 0.6f, 0.3f, 0.1f },

}

};

const TFloat3x3 c_ControlPointsY =

{

{

{ 0.2f, 0.8f, 0.5f },

{ 0.6f, 0.9f, 0.3f },

{ 0.7f, 0.1f, 0.4f },

}

};

const TFloat3x3 c_ControlPointsZ =

{

{

{ 0.6f, 0.5f, 0.3f },

{ 0.7f, 0.1f, 0.9f },

{ 0.8f, 0.4f, 0.2f },

}

};

void WaitForEnter ()

{

printf("Press Enter to quit");

fflush(stdin);

getchar();

}

float QuadraticBezier (const TFloat3& p, float t)

{

float s = 1.0f - t;

float s2 = s * s;

float t2 = t * t;

return

p[0] * s2 +

p[1] * 2.0f * s * t +

p[2] * t2;

}

float BiquadraticBezierPatch(const TFloat3x3& p, float u, float v)

{

TFloat3 uValues;

uValues[0] = QuadraticBezier(p[0], u);

uValues[1] = QuadraticBezier(p[1], u);

uValues[2] = QuadraticBezier(p[2], u);

return QuadraticBezier(uValues, v);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// how many values to display on each axis. Limited by console resolution!

const int c_numValues = 4;

printf("Bezier rectangle:n");

for (int i = 0; i < c_numValues; ++i)

{

float iPercent = ((float)i) / ((float)(c_numValues - 1));

for (int j = 0; j < c_numValues; ++j)

{

if (j == 0)

printf(" ");

float jPercent = ((float)j) / ((float)(c_numValues - 1));

float valueX = BiquadraticBezierPatch(c_ControlPointsX, jPercent, iPercent);

float valueY = BiquadraticBezierPatch(c_ControlPointsY, jPercent, iPercent);

float valueZ = BiquadraticBezierPatch(c_ControlPointsZ, jPercent, iPercent);

printf("(%0.2f, %0.2f, %0.2f) ", valueX, valueY, valueZ);

}

printf("n");

}

printf("n");

WaitForEnter();

return 0;

}

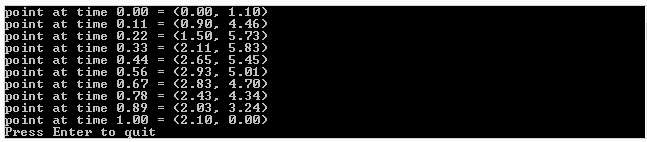

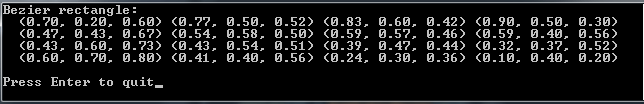

And here is the output it gives:

Note that in the program above, I evaluate the surface points by evaluating one axis and then the other. This is basically the same as how I explained it at the top, where I’m effectively animating the control points over distance, then evaluating the curve slice of the surface at that specific distance.

You could also write it another way though, where you literally expand the mathematical formula to get just one expression to evaluate that takes all control points at once. I like the simplicity (of understanding) of the method I used, but the other method works just as well.

The Rendering

It’s easy enough to calculate values on a Bezier Rectangle, but what if you want to draw one?

One way is to tessellate it, or break it up into triangles and then render the triangles. You can think of it like trying to render a grid, where each point of the grid is moved to be where ever the Bezier rectangle function says it should be.

Raytracing against these objects in the general case is very difficult however, because it basically comes down to solving equations of very high degree.

Raymarching against these objects is also difficult unfortunately because while raymarching only needs to know “am i above the shape, or underneath it?”, knowing what u,v to plug into the equation to get the height most relevant to a random point in space is also very difficult. Not as difficult as the raytracing equations, but probably just as much out of reach.

But never fear, as always, you can cheat!

If you read my post about one dimensional (explicit) Bezier curves (One Dimensional Bezier Curves), you may remember that math gets easier if you use one dimensional control points. The same is actually true with Bezier rectangles!

For the ray marching case, you can march a point through space, and plug the x,z coordinate of the point into the Bezier rectangle function as u,v values and the number that comes out you can treat as a y coordinate.

Now, ray marching a Bezier rectangle is the same as ray marching any old height map (check links section for more info on that).

What I did in my demos, is since i knew that the curve was constrained to 0-1 on the x and z axis, and the y axis min and max was the control point min and maxes, I did a raytrace of that bounding box to get a minimum and maximum distance that the ray was inside that box. From there, I did raymarching from that min time to the max time along the ray, considering the ray as hitting the surface whenever the distance from the ray to the surface on the y axis (rayPos.y – bezierRectangle.y) changed sign.

After I had a hit, I got the height of the curve slightly offset on the x axis, then slightly offset on the z axis to get a triangle that I could calculate a surface normal from, to do lighting and shading with.

There is room for improvement in the ray marching though. I evenly divide the space through the box by a specific amount to control the size of the steps. A better way to do this I think would be to get the gradient of the function and use that to get a distance estimate (check links section below for more information). I could use that value to control the distance the ray marches at each step, and should be able to march through the box much quicker.

Also, as the link on terrain marching explains, you can usually take farther steps when the ray is farther from the camera, because the eye notices less detail. I removed that since the Bezier rectangles are pretty close to the camera, but it probably still would be helpful. Also, it would DEFINITELY be helpful in the case of the “Infinite Bezier Rectangles” scene.

I am pretty sure you could directly raytrace an explicit Bezier rectangle (one who has one dimensional control points) – at least for low degrees. I personally don’t know how you would do that, but I think it might boil down to solving a 4th degree function or something else “reasonable” based on a similar question I had about Bezier triangles on the mathematics stack exchange site (link below).

Another Way To Render

There is another way to render Bezier surfaces using ray based methods that I didn’t use but want to mention.

A property of Bezier curves and surfaces is that they are guaranteed to be completely contained by the convex hull created by their control points.

Another property of Bezier curves and surfaces is that you can use the De Casteljeau algorithm to cut them up. For instance you could cut a Bezier curve into two different Bezier curves, and the same holds for Bezier surfaces.

Using these two properties, there is an interesting way to be able to tell if a ray intersects a bezier curve or not, which is:

- If the line misses the convex hull, return a miss

- If the convex hull is smaller than a pixel, return a hit

- Otherwise, cut the Bezier object into a couple smaller Bezier objects

- Recurse for each smaller Bezier object

Yes, believe it or not, that is a real technique! It’s called Bezier Clipping and there is a research paper in the links section below that talks about some of the details of using that rendering technique.

Links

Lastly, I wanted to mention that the above is completely about Bezier rectangles, but there is no reason you couldn’t extend these rectangles to use rational Bezier functions, or be based on B-splines or NURBS, or even go a different direction and make hermite surfaces or catmull-rom surfaces, or even make surfaces that used exotic basis functions of your own crafting based on trigonometric functions or whatever else!

Here are the shadertoy demos I made:

Shadertoy: Cubic Bezier Rectangle

Shadertoy: Quadratic Bezier Rectangle

Shadertoy: Infinite Bezier Rectangles

And some other links about this stuff:

IQ – terrain raymarching

IQ – distance estimation (using function gradients)

Math Stack Exchange – Ray intersection with explicit (1 axis) Bezier triangle?

Math Stack Exchange – Intersect Ray (Line) vs Quadratic Bezier Triangle

Bézier Surfaces: de Casteljau’s Algorithm

Ray Tracing Triangular Bézier Patches (including Bezier clipping)

Wikipedia: Bezier Surface

Wikipedia: Bezier Triangle