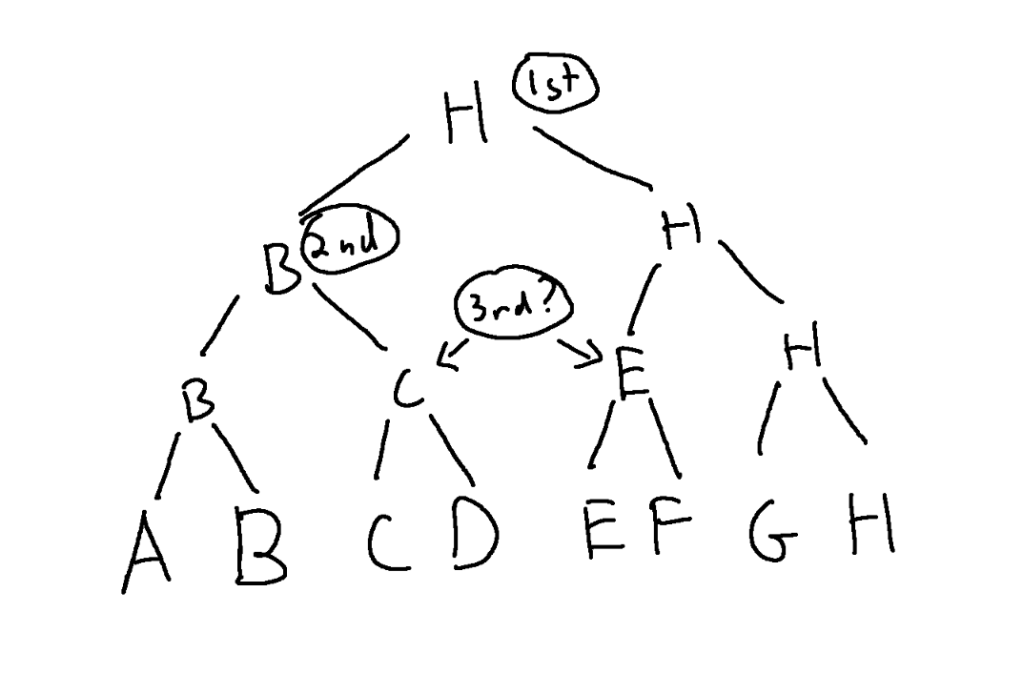

The last post showed how random Hamiltonian cycles on a graph (a path that visits each node exactly once) could efficiently handle ranking of a large number of items, by doing sparse pairwise voting (https://blog.demofox.org/2023/09/01/sparse-pairwise-voting-or-tournaments-implementing-some3-voting/).

That algorithm needed to generate multiple Hamiltonian cycles which didn’t use any graph edges already used by other cycles, and I didn’t like that it did this by generating cycles randomly until it found one that is valid. The “randomly generate candidates until success” meant an erratic runtime that might not even find a solution in a reasonable amount of time.

This post shows a way to generate those cycles in a straightforward way and compares the resulting cycles to the algorithm in the previous post. The algorithm requires a prime number count of nodes, but if you don’t have a prime number count of nodes, you can pad the graph with extra nodes to make it reach the next prime number. If the cycles are for voting, you can make those padding nodes automatically lose to real nodes, without needing to do an actual vote. This algorithm also works with non prime number amounts of nodes if you relax what “works” means a bit; instead of making cycles, it will sometimes make isolated loops, but we talk about how that can still be useful.

The code that goes with this post lives at https://github.com/Atrix256/PairwiseVoting. The visual “star” diagrams were made with drawgraphs.py. The csv files for the graphs were made by main.cpp.

The Algorithm

The algorithm is pretty straightforward.

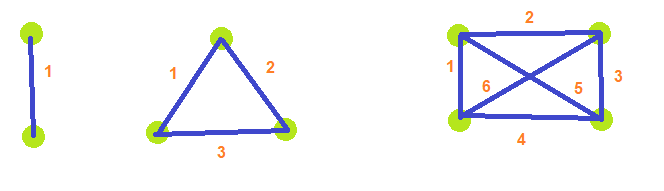

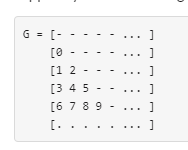

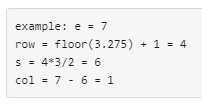

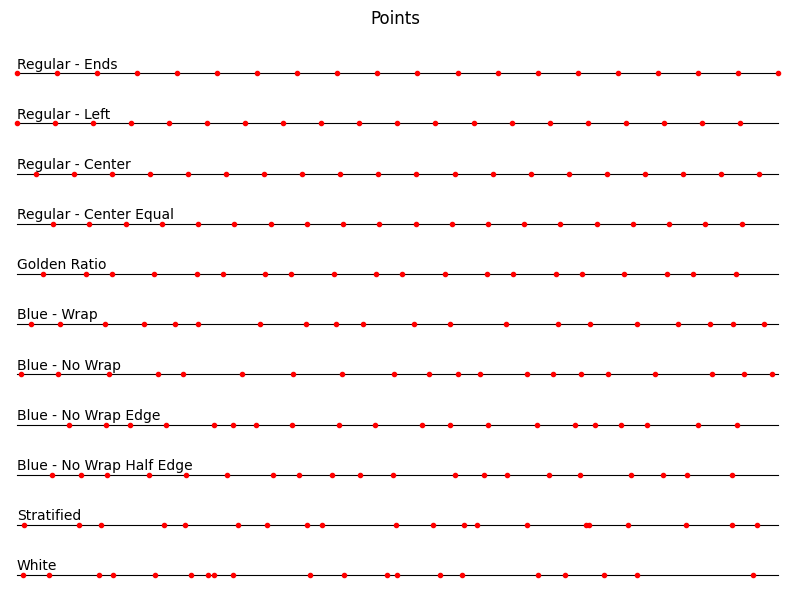

If you have N nodes and N is a prime number, you loop from 0 to N-1. nodeA is the loop index. nodeB is (nodeA + 1) % N. This is the first cycle.

For the second cycle, you loop again. nodeA is the loop index. nodeB is (nodeA + 2) % N.

For the third cycle, you loop again. nodeA is the loop index. nodeB is (nodeA + 3) % N.

To get all cycles, you repeat this, for each integer from 1 to N/2, but not including N/2.

Let’s see an example.

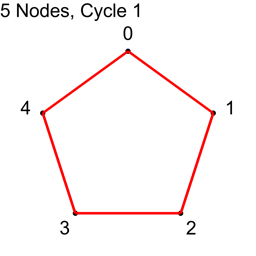

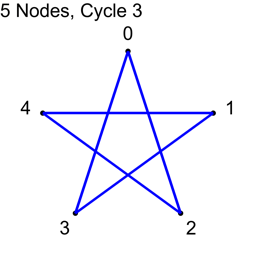

Example 1 – Five Nodes

For the first cycle, we use each node index 0,1,2,3,4 as nodeA, and add 1 to each, modulo 5, to get nodeB.

| Node A | Node B | Connection |

| 0 | 1 | 0 – 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 – 2 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 – 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 3 – 4 |

| 4 | 0 | 4 – 0 |

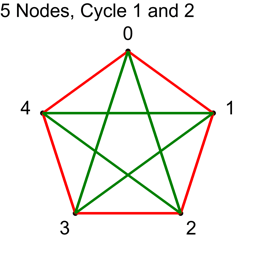

We next add 2:

| Node A | Node B | Connection |

| 0 | 2 | 0 – 2 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 – 3 |

| 2 | 4 | 2 – 4 |

| 3 | 0 | 3 – 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 – 1 |

N/2 is 2.5, so we should stop at this point. Let’s see what happens if we do 3 anyways.

| Node A | node B | Connection |

| 0 | 3 | 0 – 3 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 – 4 |

| 2 | 0 | 2 – 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 – 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 4 – 2 |

We got the same connections when we added 3, as when adding 2. We’ll see why shortly.

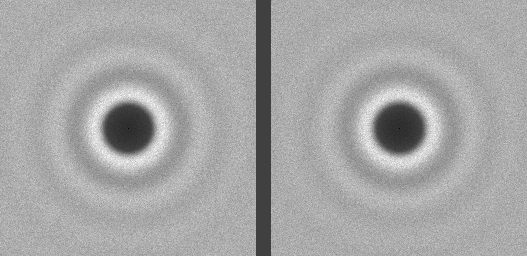

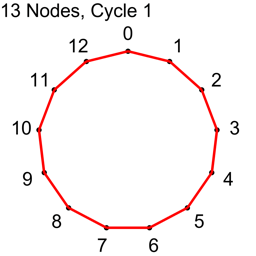

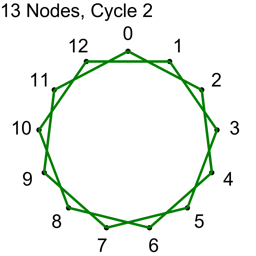

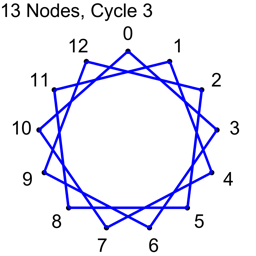

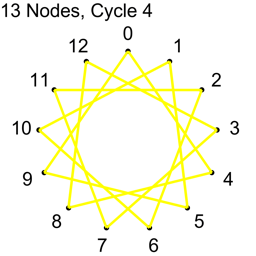

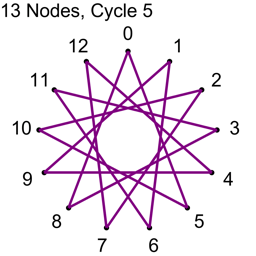

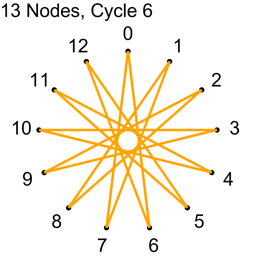

Example 2 – Thirteen Nodes

Just the diagrams, one cycle at a time, because otherwise it’s too messy.

Why Does This Work?

For the first cycle, we start with every node we have as nodeA, then add 1 and modulo by N to get each nodeB. That gives us N connections, and they are all unique. We have used up all the connections where the nodes are 1 index apart and no other cycle is going to make a connection with nodes that are 1 index apart. We know that this is a cycle and that we can get from any node to any other node because you can subtract 1 or add 1 repeatedly to get from any index to any other index.

For the second cycle, we do the same but add 2 and modulo by N to get nodeB. We again have N connections and they are all unique. We also have used up all the connections where the nodes are 2 indices apart and no other cycle is going to make any connection where the nodes are 2 indices apart.

For the second cycle, we can also get from any node to any other node in this cycle, but it’s less obvious why. When working with the integers modulo N, you have something called a ring, which is a type of group. If you start at any number on the ring, and repeatedly add some number M which is relatively prime to N (no common factors other than 1), you will visit all numbers 0 to N-1, and will visit them all once before repeating any. When N is a prime number, then EVERY number less than N is relatively prime to N.

You can try this yourself:

- Pick some prime number N

- Pick any number M between 1 and N-1.

- Starting at zero (or any other value), add M, modulo by N, and write out the value.

- Repeat step 3 and you’ll see that you’ll visit all N numbers and after N steps you will get back to where you started.

Let’s do this with N=7 and M=2:

| Step | Value | Next Value |

| 1 | 0 | (0 + 2) % 7 = 2 |

| 2 | 2 | (2 + 2) % 7 = 4 |

| 3 | 4 | (4 + 2) % 7 = 6 |

| 4 | 6 | (6 + 2) % 7 = 1 |

| 5 | 1 | (1 + 2) % 7 = 3 |

| 6 | 3 | (3 + 2) % 7 = 5 |

| 7 | 5 | (5 + 2) % 7 = 0 |

| 8 | 0 | (0 + 2) % 7 = 2 |

So, when N is prime, every time we add a specific value greater than 0 and less than N to all the node indices, we’ll get a cycle that uses edges that no other cycle will give us.

Why Start Cycles at 1 and Stop at N/2?

There are two explanations for why this is. One is a mathematical explanation and the other is a brick wall. Let’s look at the brick wall first, then talk about the mathematical reason.

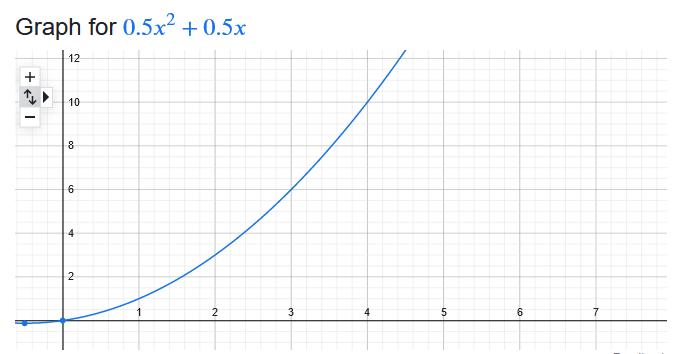

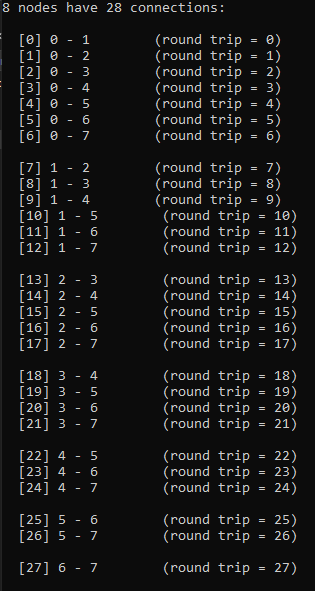

If you have N nodes in a graph, the total number of connections you can make between nodes is N * (N-1) / 2. Tangent: if you think that looks like Gauss’ formula, you are correct! It’s Gauss’ formula for N-1.

Returning to example 1, that had 5 nodes which means there are 5*4/2 = 10 total connections.

Each Hamiltonian cycle on that graph takes 5 connections away from all possible connections, and with 10 connections total, that means there can only be 2 cycles.

5/2 is 2.5, so we do cycle 1, then cycle 2, and stop before we do cycle 3.

We literally cannot do more than 2 cycles when there are 5 nodes.

Looking at example 2, there are 13 nodes, which means there are 78 total connections.

Each cycle takes 13 connections, so all connections are used up after 6 cycles.

13/2 is 6.5, so we know to stop at 6 before going to 7.

The brick wall limitation is that after N/2 cycles, we have no more edges to make cycles out of!

The mathematical explanation involves rings. To quote the previous section: When working with the integers modulo N, you have something called a ring, which is a type of group.

In rings, there is an interesting connection between the numbers less than N/2 and the numbers greater than N/2. Adding a number greater than N/2 is the same as subtracting a number less than N/2. As an example, let’s look at N=7 in the table below. We can see that adding 5 is the same as subtracting 2.

| Starting Value | (Starting Value + 5) % 7 | (Starting Value – 2) % 7 |

| 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 1 | 6 | 6 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | 4 | 4 |

This means that if we have a connection where nodeB = (nodeA + 5) % 7, it is exactly the same as the connection where nodeA = (nodeB + 2) % 7. More plainly, cycle 5 will make the same connections as cycle 2. The nodeA and nodeB values will be swapped, but it will be the same connections.

Cycle N/2 is the point where positive numbers become the same as smaller negative numbers, so that is where we stop. Since all prime numbers (greater than 2) are odd, N/2 will never be an integer, so we don’t have to think about what to do at exactly N/2.

What if N isn’t Prime?

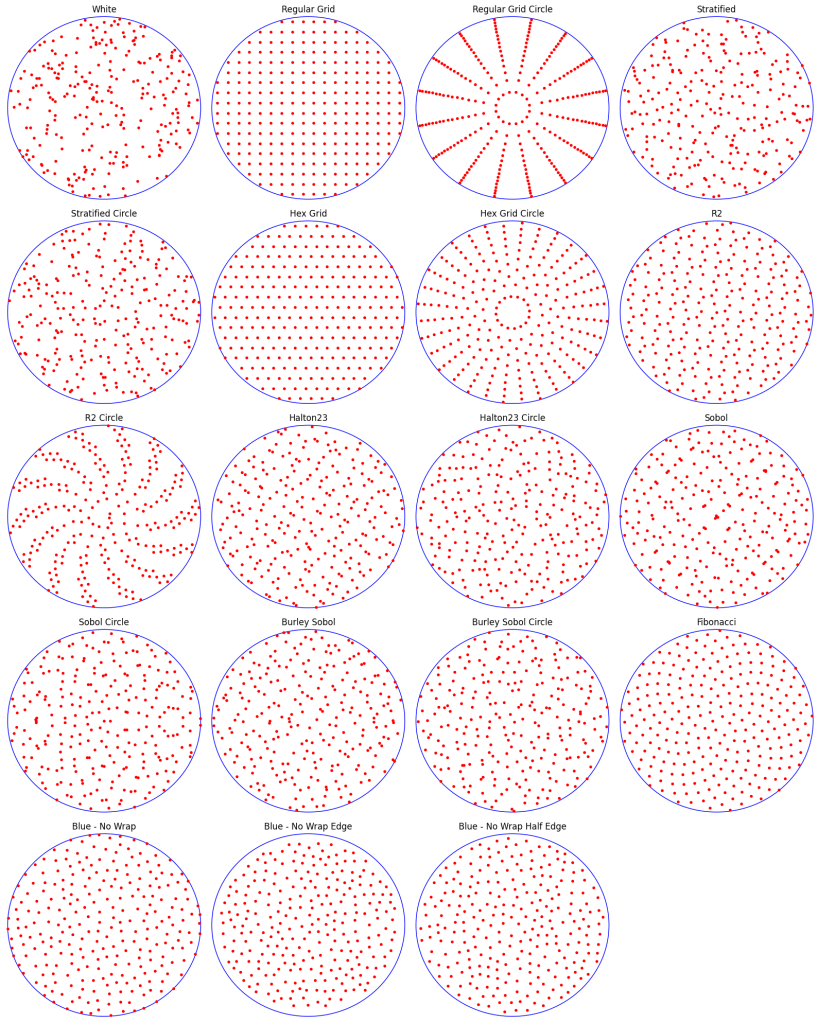

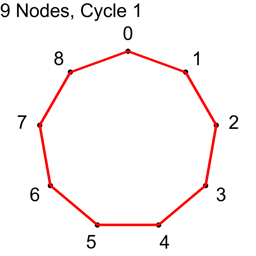

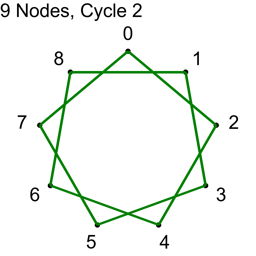

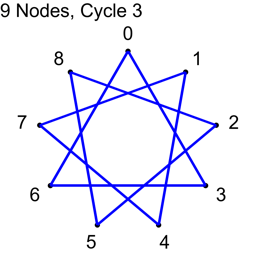

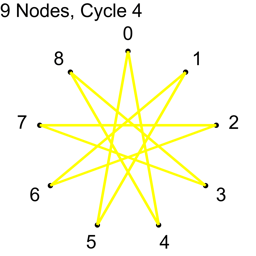

If N isn’t prime, not all “cycles” will be cycles. The algorithm will visit all nodes, but there will not be a path from each node to every other node. Here are the cycles for where N=9.

With N=9, only cycles 1,2 and 4 make cycles. Cycle 3 makes three loops: 0,3,6 and 1,4,7 and 2,5,8. If you wanted to use this algorithm to make connections in a graph for voting or for a tournament, you could still do so, but the first cycle you do should be a coprime (cycle 1 is an easy one to choose as the first cycle), so that the graph was connected from the beginning, and these loops would increase connectivity of the graph, without having to be fully fledged Hamiltonian cycles.

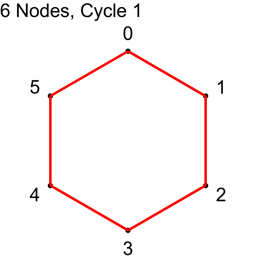

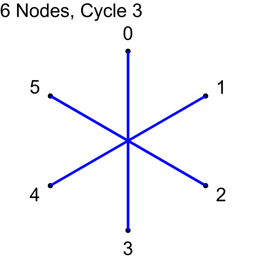

Allowing N not to be prime also allows an even numbered N. In that case, when you create cycles from 1 to N/2, should you include N/2 or not? Let’s see what happens when N=6, for cycles 1,2 and 3.

What happened to cycle 3?

Cycle 3 made all the connections where the difference between the node indices was 3, and it made 6 connections. Unfortunately, there are only 3 unique connections where the difference in node indices is 3: 0-3, 1-4, 2-5. Cycle 3 added the following redundant connections: 3-0, 4-1, 5-2. The answer about whether you should include N/2 if using a non prime number of nodes is ultimately up to you, but you should know that when you do so, you’ll get redundant connections. On the flip side, if you don’t include them, those are node connections that you will never be able to make otherwise, using this algorithm. You’ll have to decide which way you want to go. You could always pad with another node to make it odd, and dodge this issue 🙂

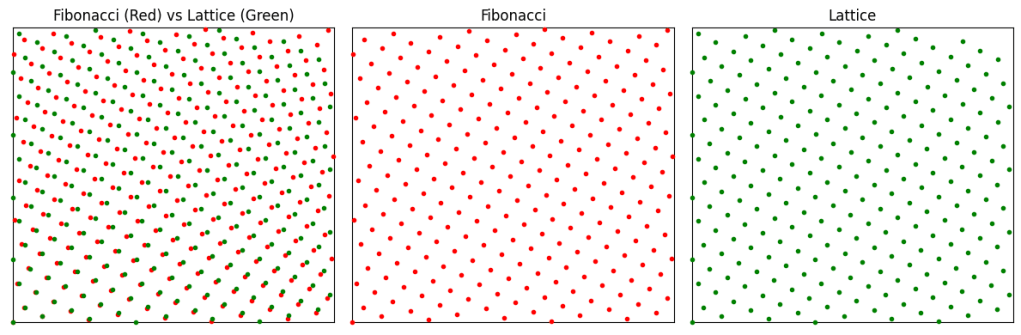

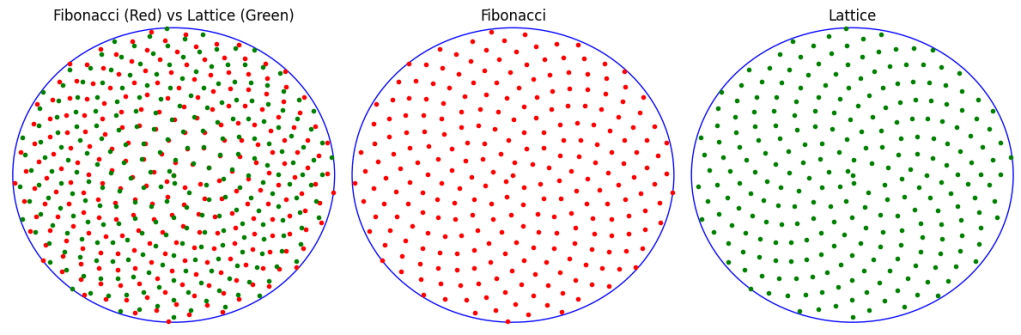

Is This Random Enough?

When you see that the first cycle gives you the connections in order 0 – 1, 1 – 2, 2 – 3, etc. you may wonder if this method is making random enough cycles.

In defense of this seeming lack of randomness, keep in mind that node indices are just arbitrary names of nodes. Two nodes that have an index difference of 1 are not any more, or less, similar than two other nodes that have an index difference of 5. The numbers are just arbitrary labels.

However, the lack of randomness does come up on subsequent cycles. Think of the path from node A to node B on graphs made this way as a simplified path finding problem. After you’ve done 1 cycle, you know you can take steps of size 1 from any node to any other node. After you’ve done 2 cycles, you know you can take steps of size 2. After 3 cycles you can take steps of size 3 and so on. Using this knowledge, you can craft a path from A to B using the largest steps to get as close as possible, then a smaller step as a remainder. This is nice and orderly, but when graph edges are taken at random, there will be shortcuts sprinkled throughout the graph. Like if in the first cycle of a 1000 node graph, if there is a link from node 0 to node 500, that will drastically reduce the length of the path between the most distant nodes.

So on one hand, the lack of randomness doesn’t matter, but on another hand, it does.

There are some ways to inject randomness into this algorithm if you want to though. One easy thing you can do is shuffle the nodes before running this algorithm. Another thing you can do is perform the cycles in a random order. If you have 1009 nodes, that gives you 1009/2=504 cycles. The last post showed that you only need a handful of cycles to get a good result if using cycles for voting or tournaments. Instead of doing cycles 1, 2, and 3, you could randomize the order and do it an order like 100, 4, 235. These points of randomization could help make up for lack of randomization in the cycles themselves, and are also helpful if you ever need multiple sets of non overlapping Hamiltonian cycles. That allows this algorithm to take in a “random seed” to get different results for different seeds, while remaining deterministic.

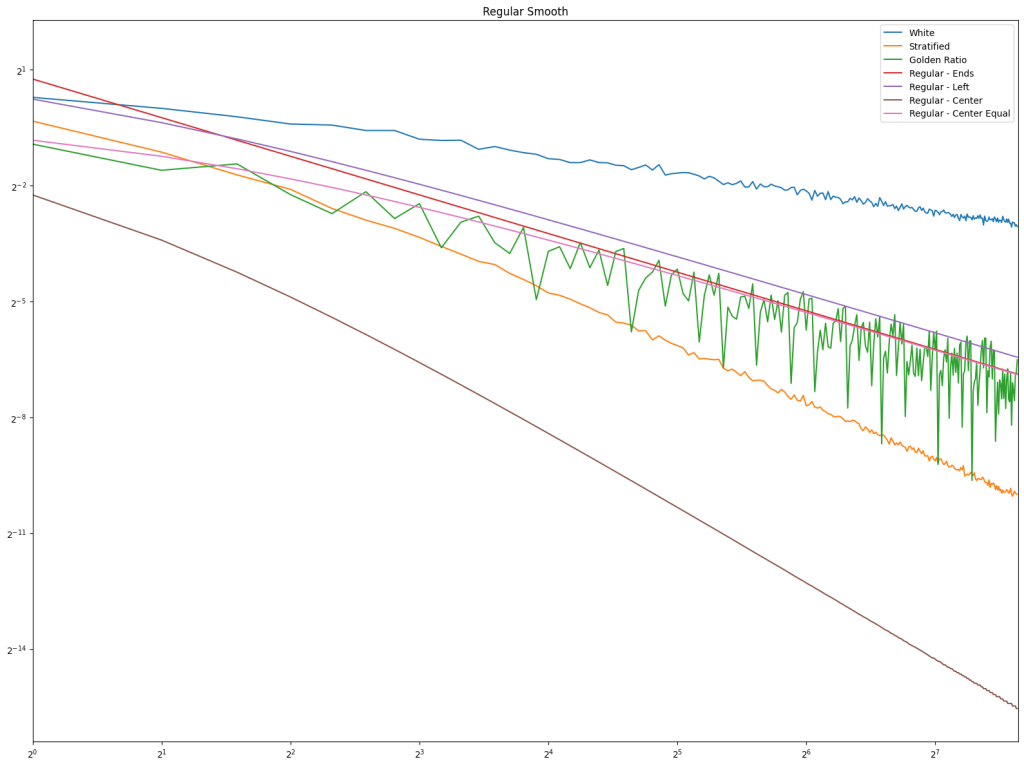

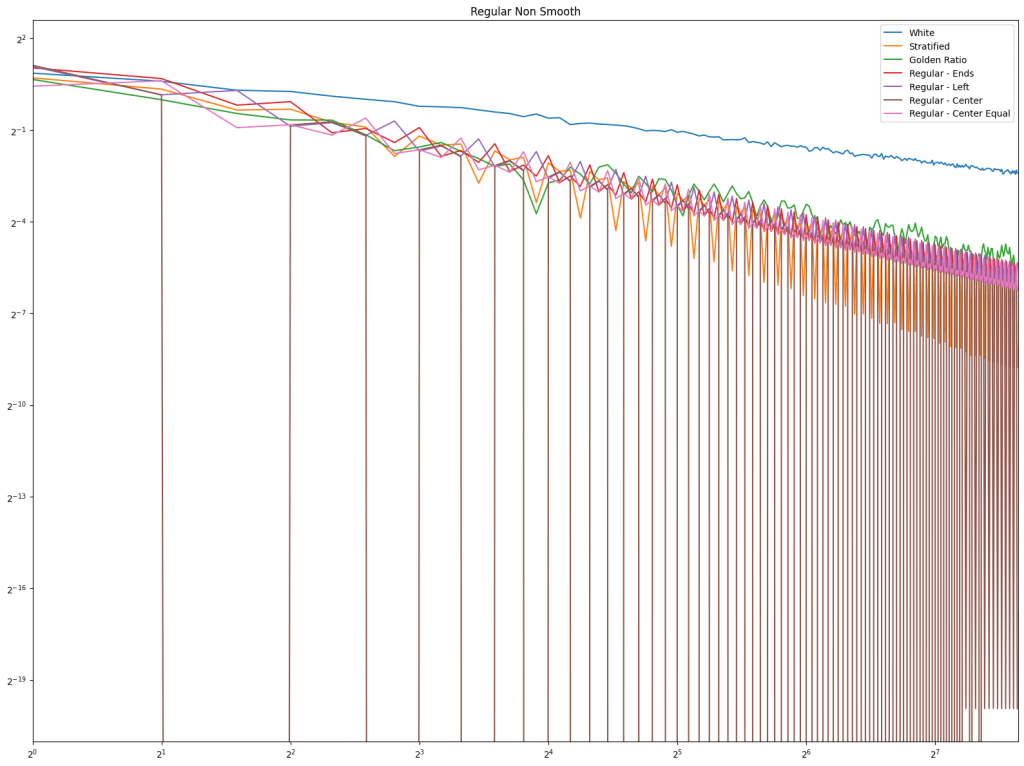

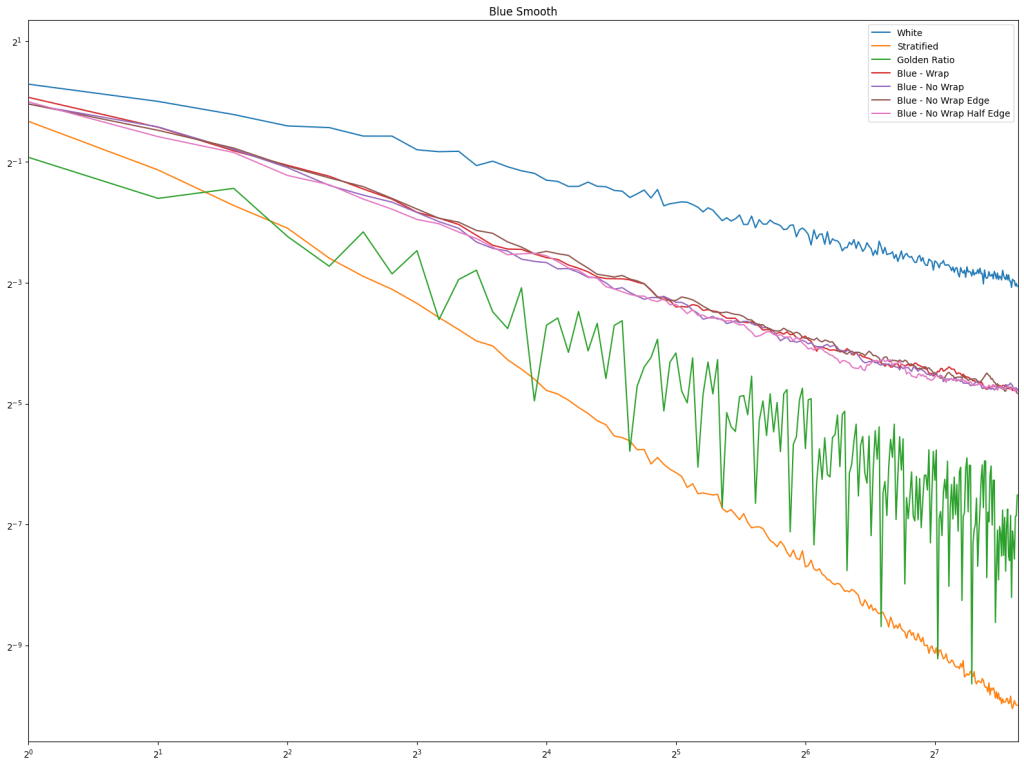

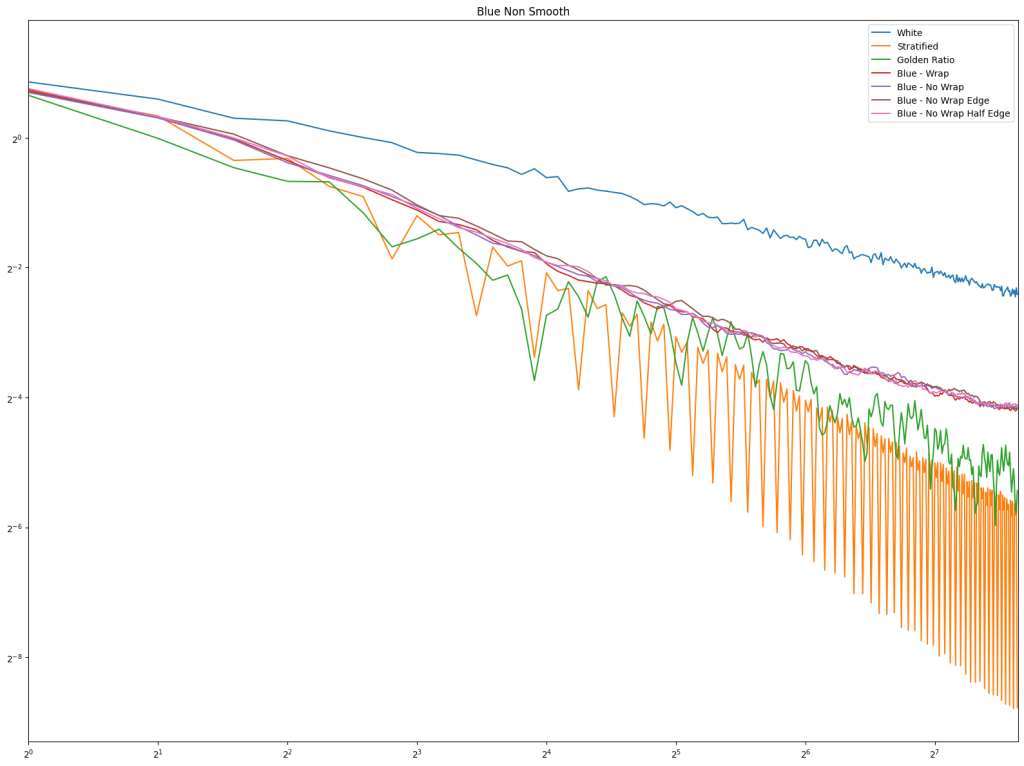

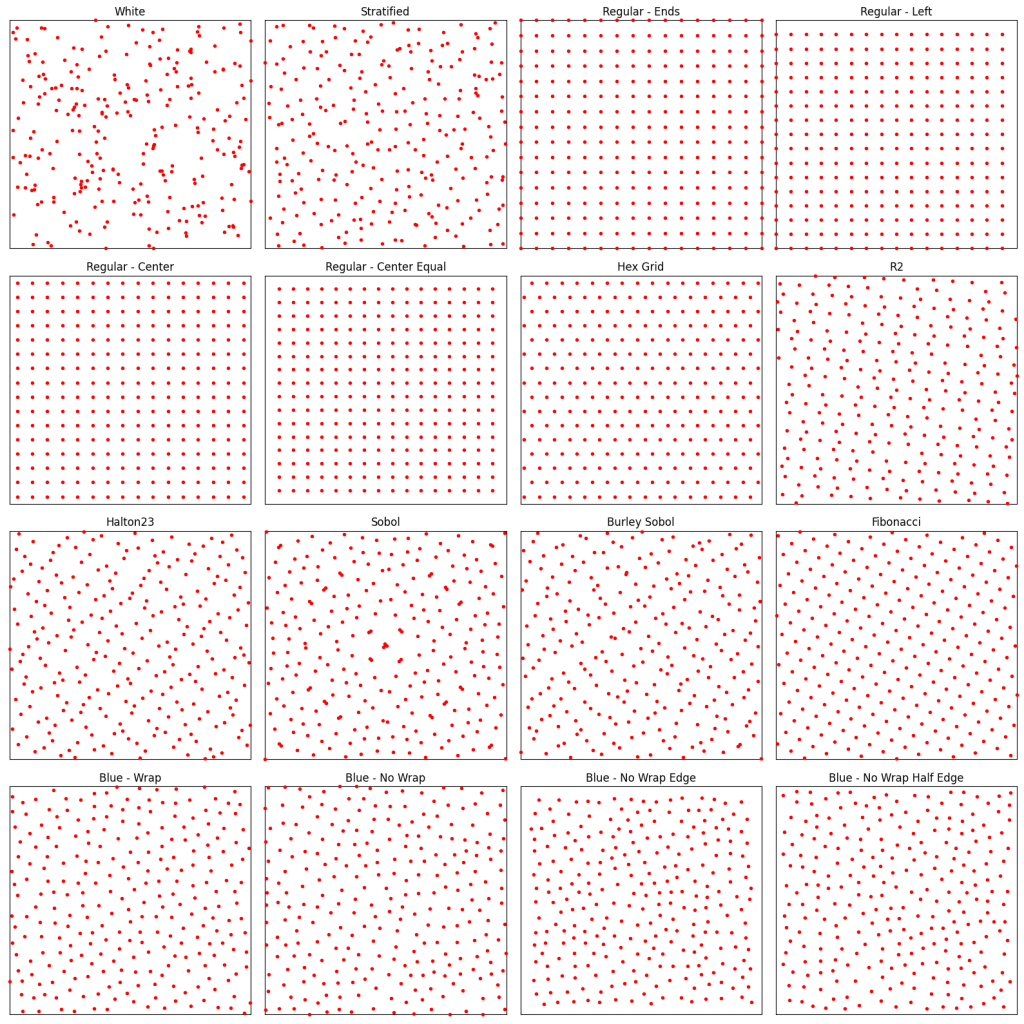

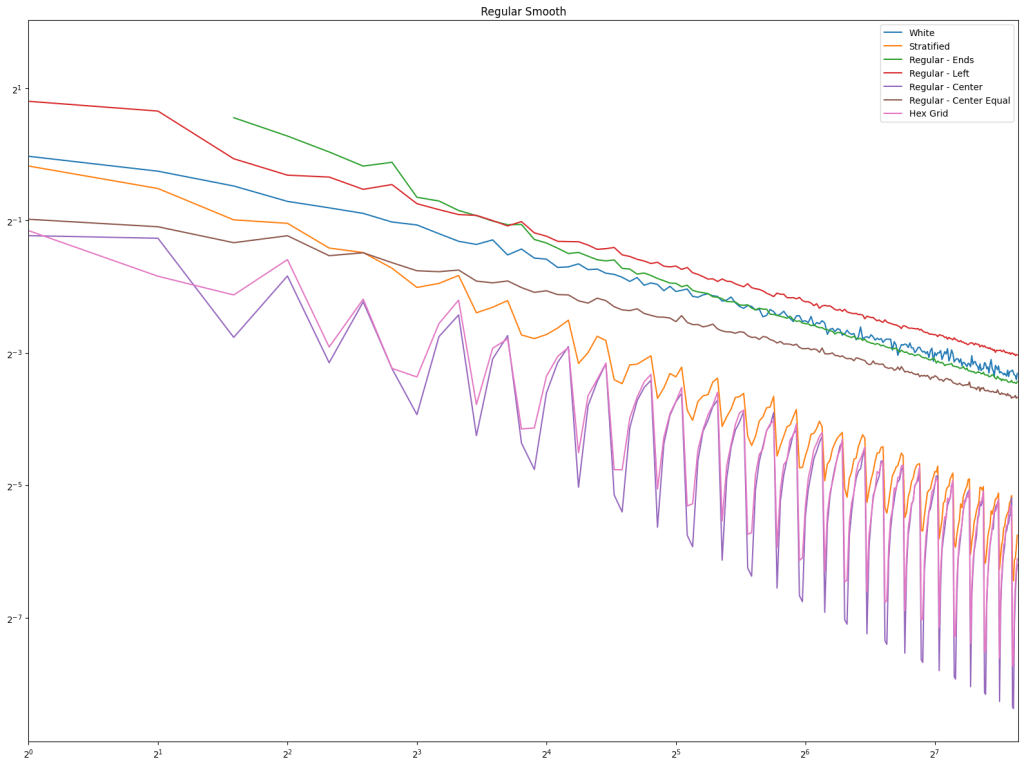

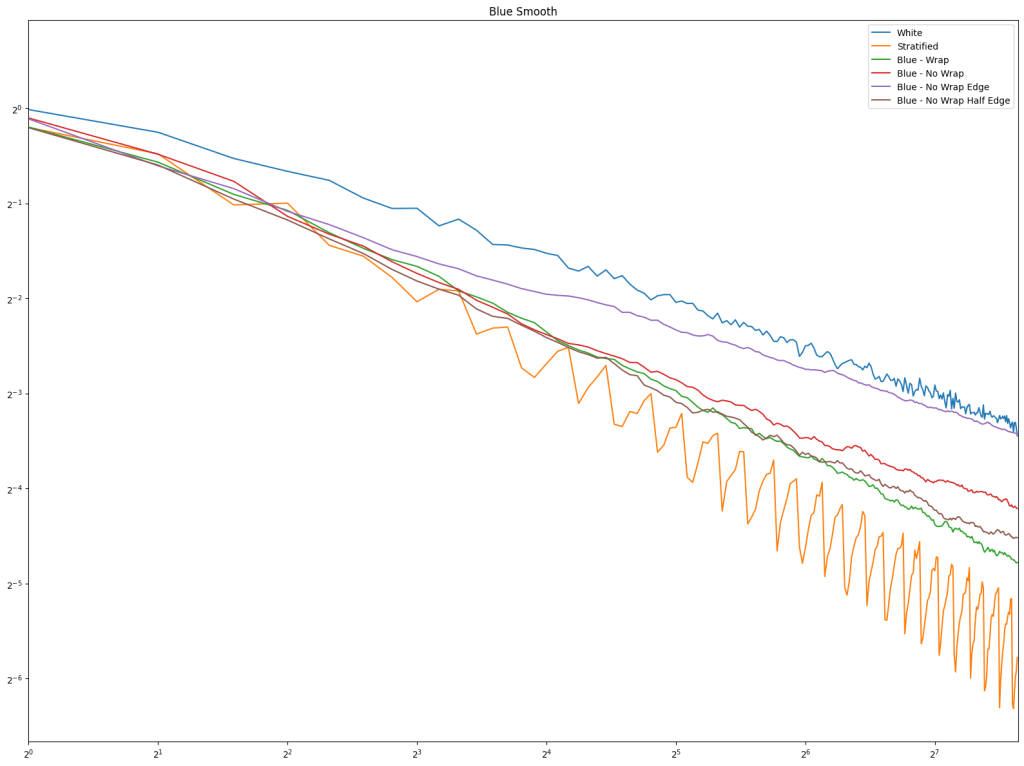

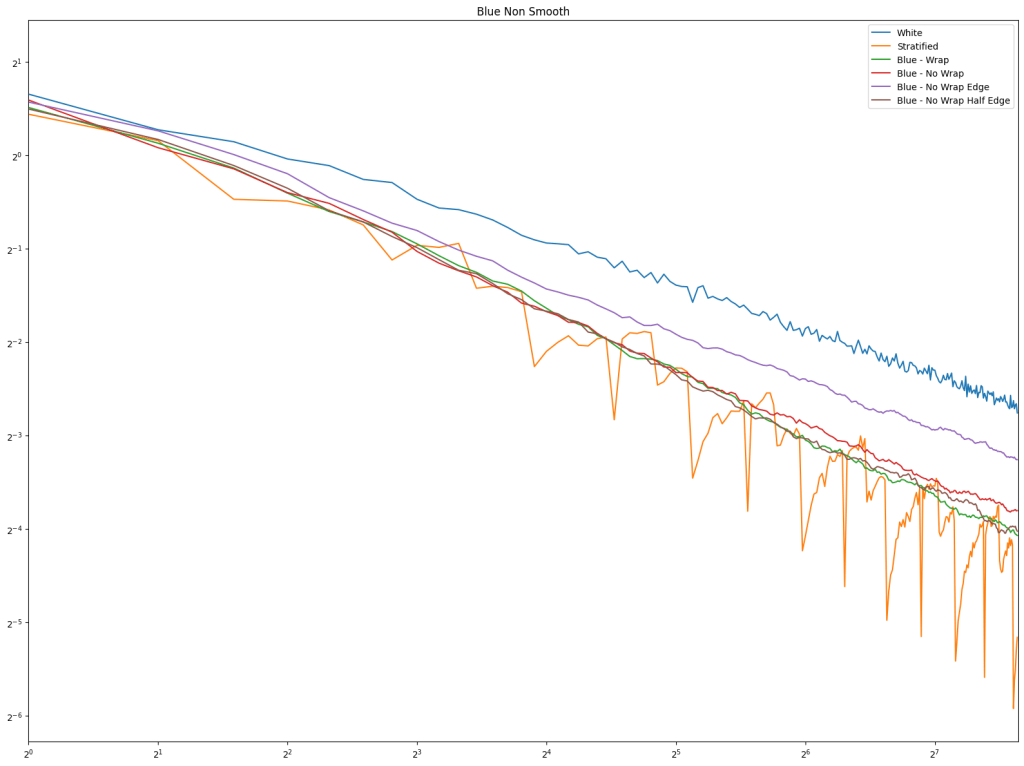

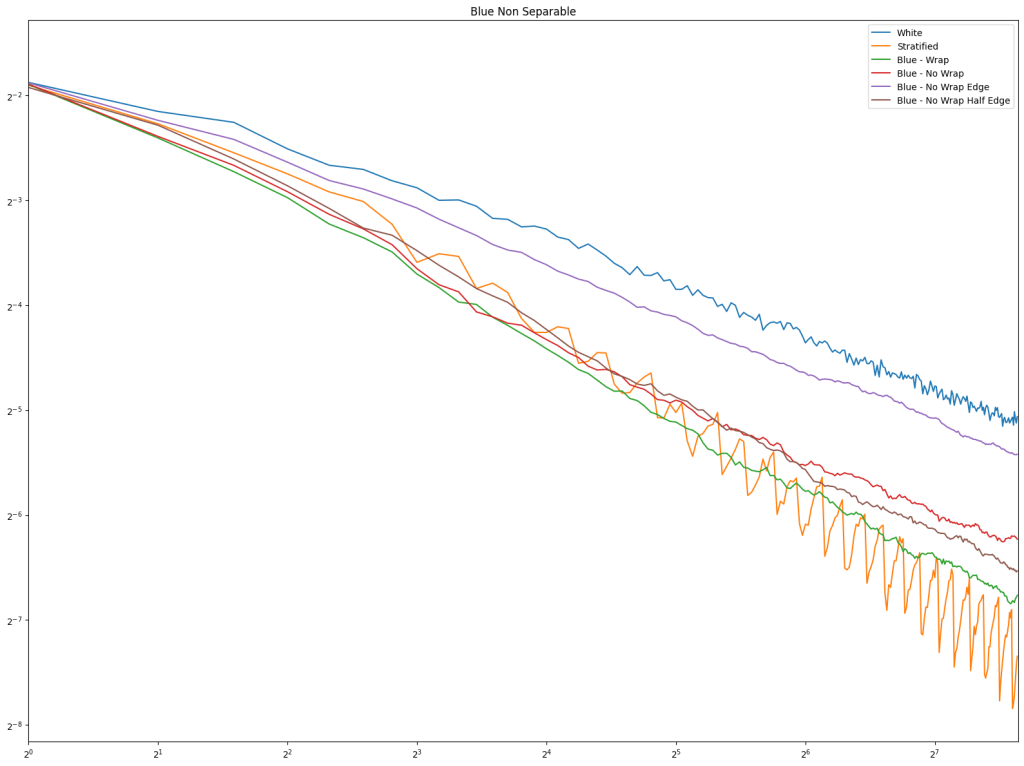

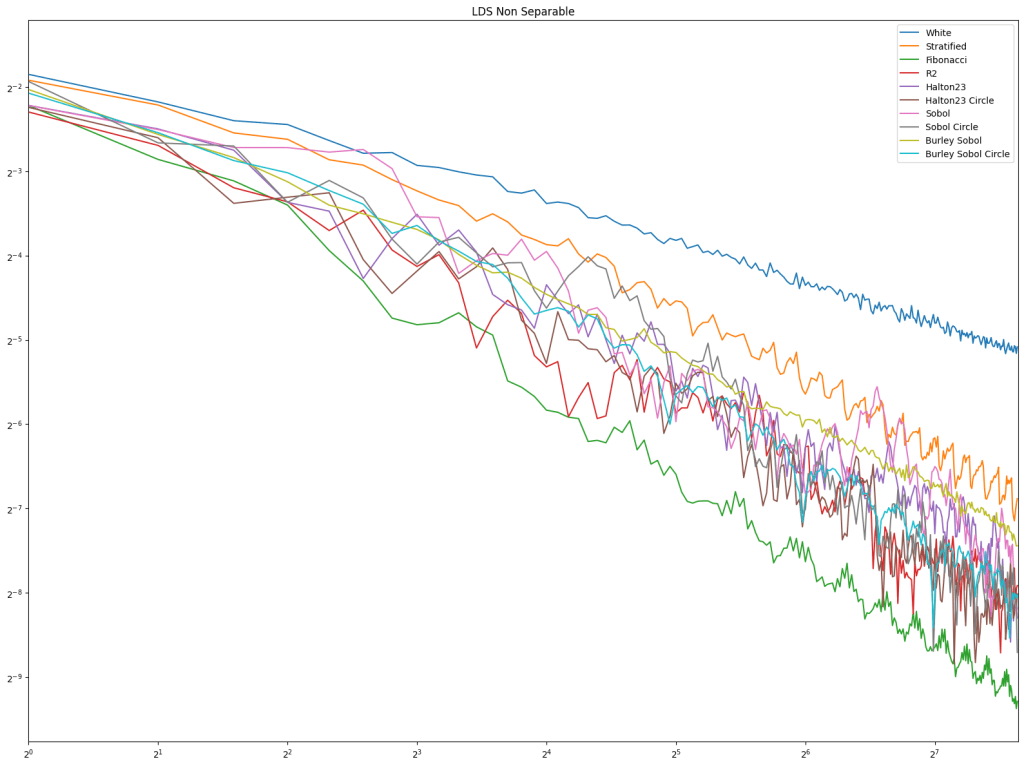

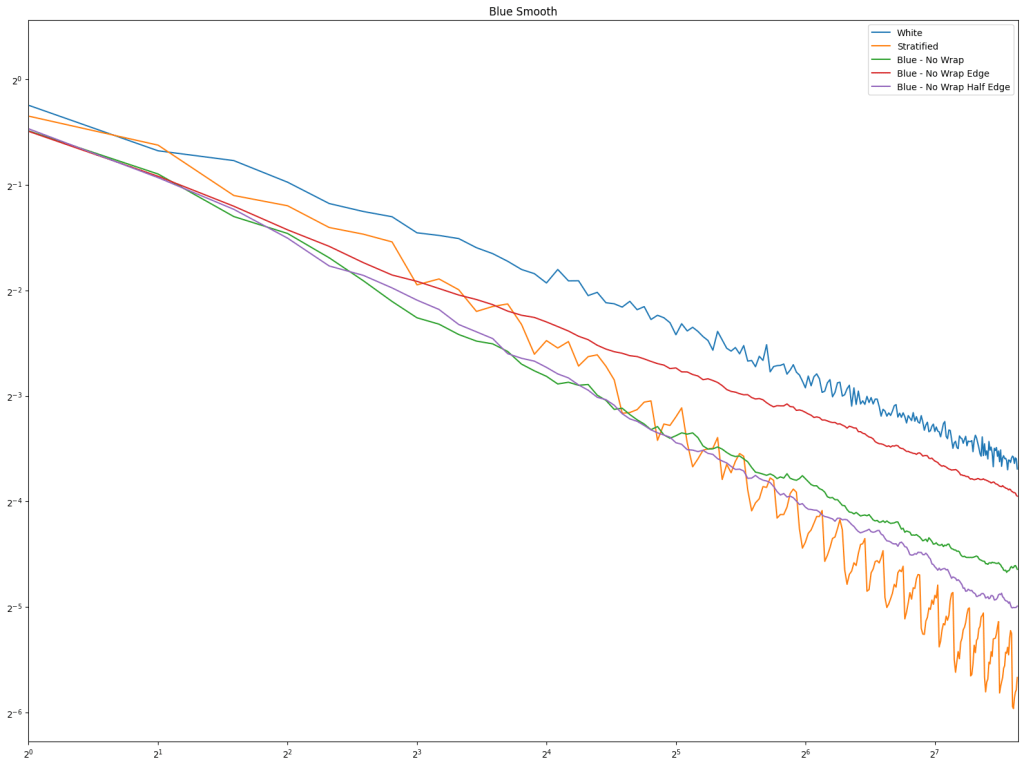

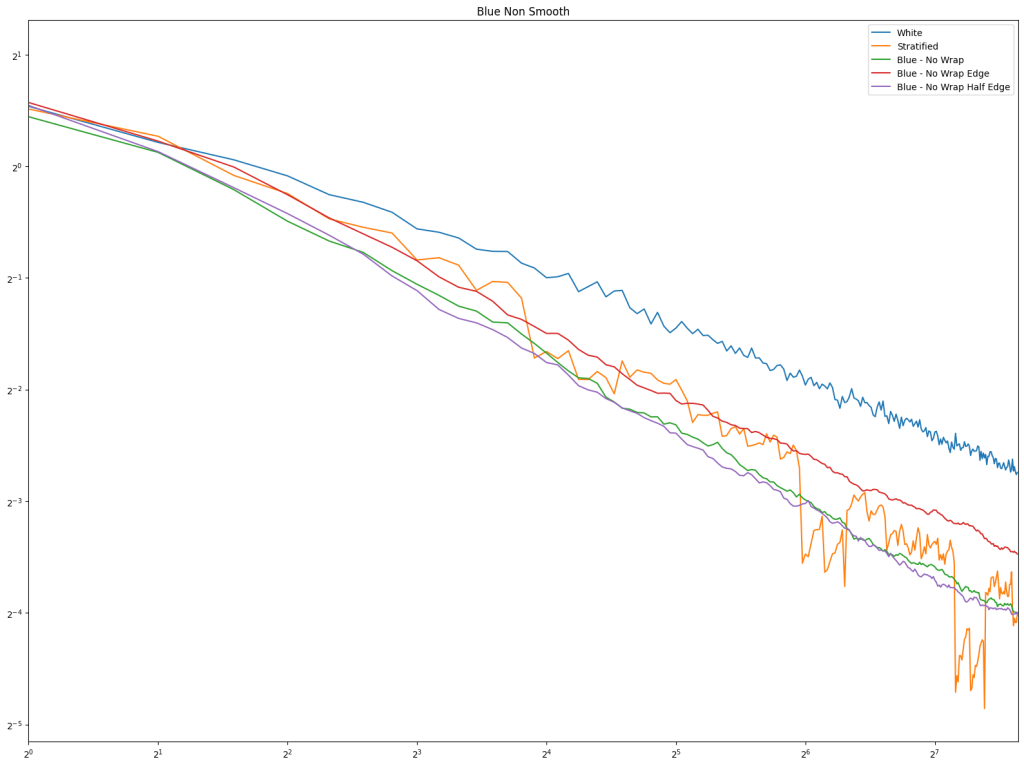

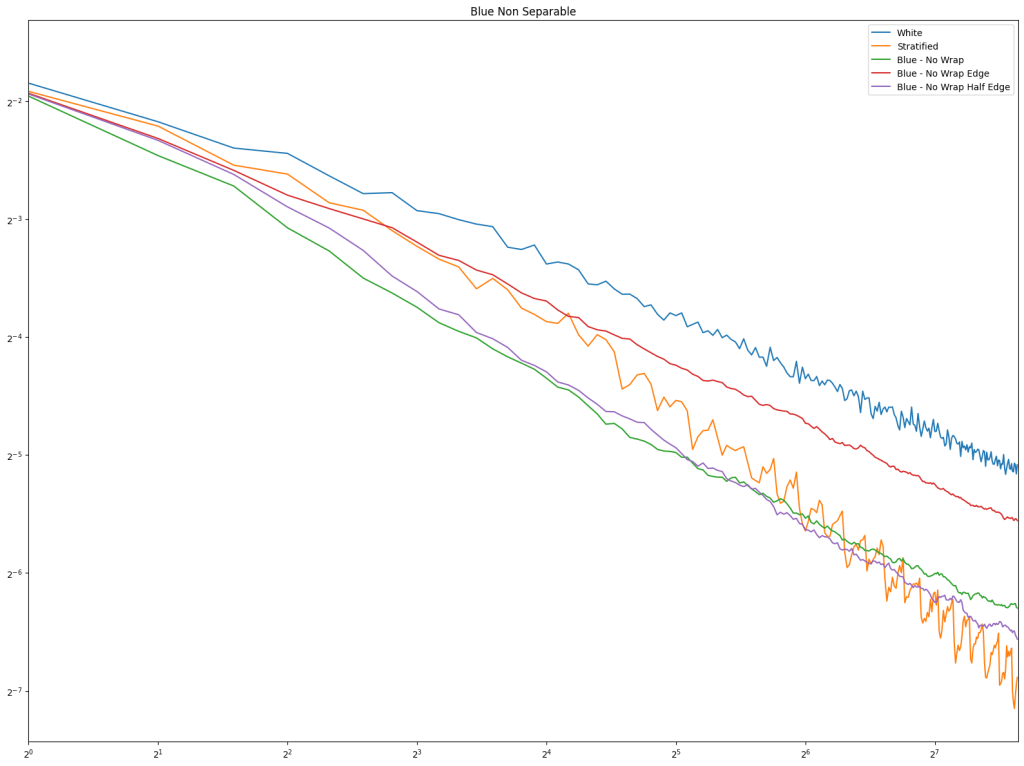

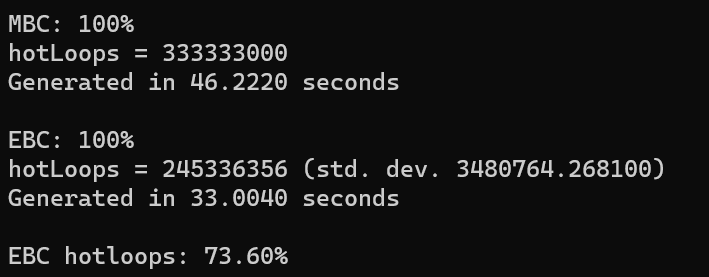

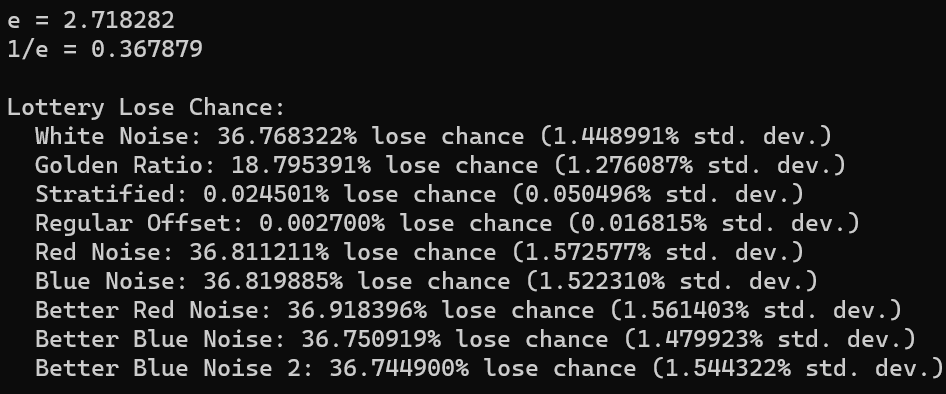

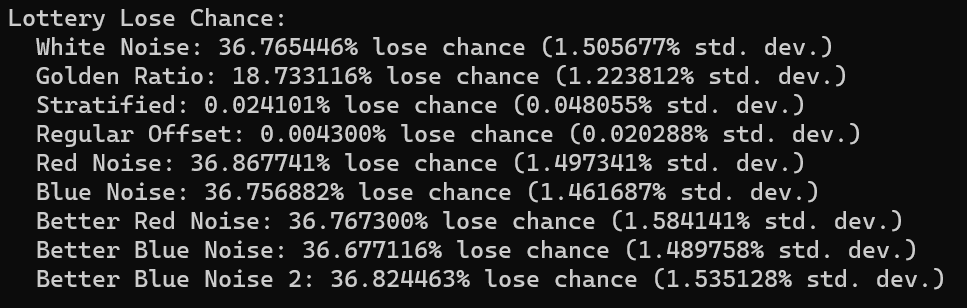

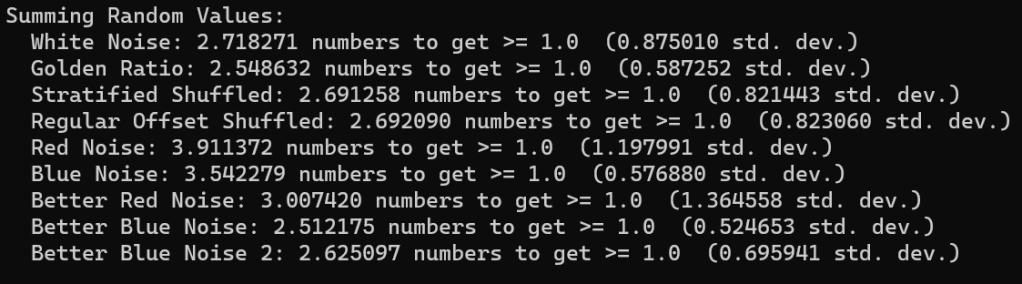

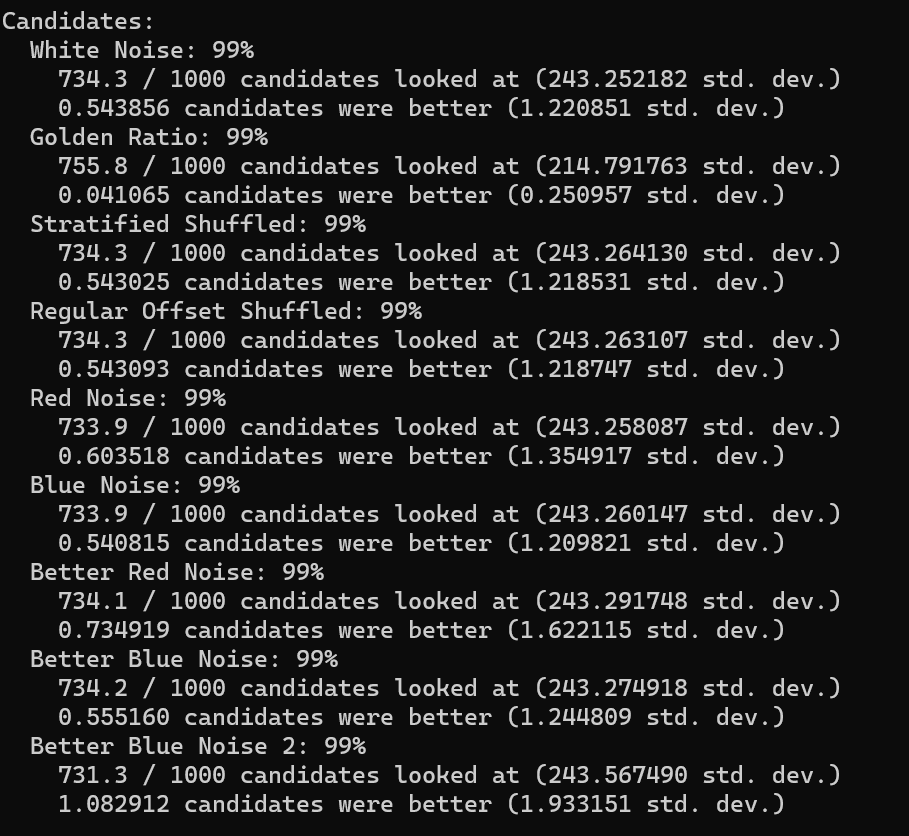

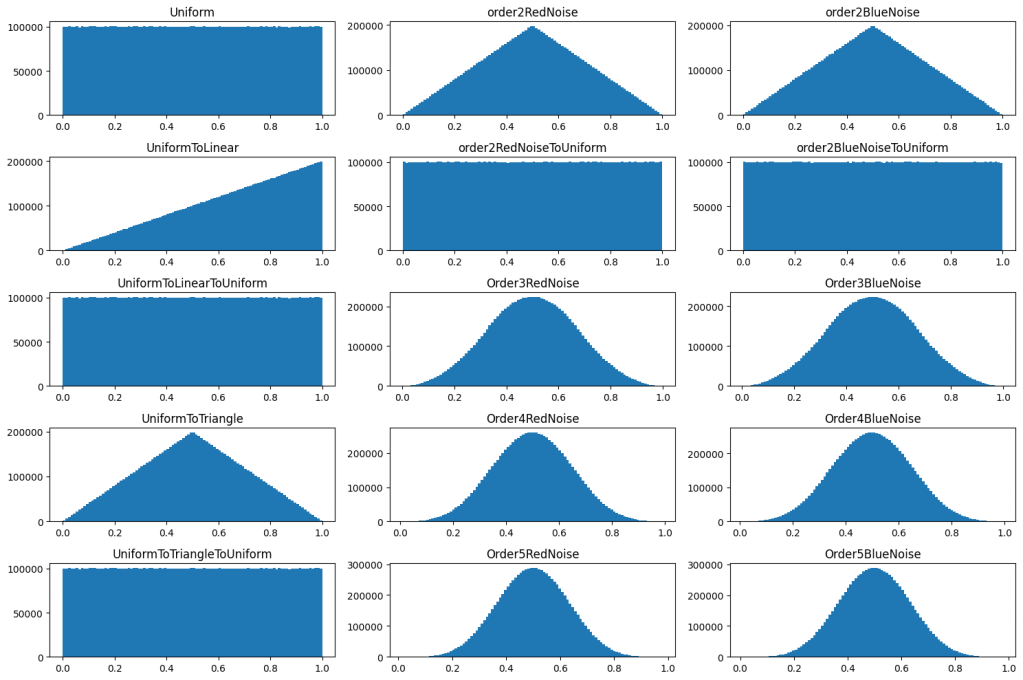

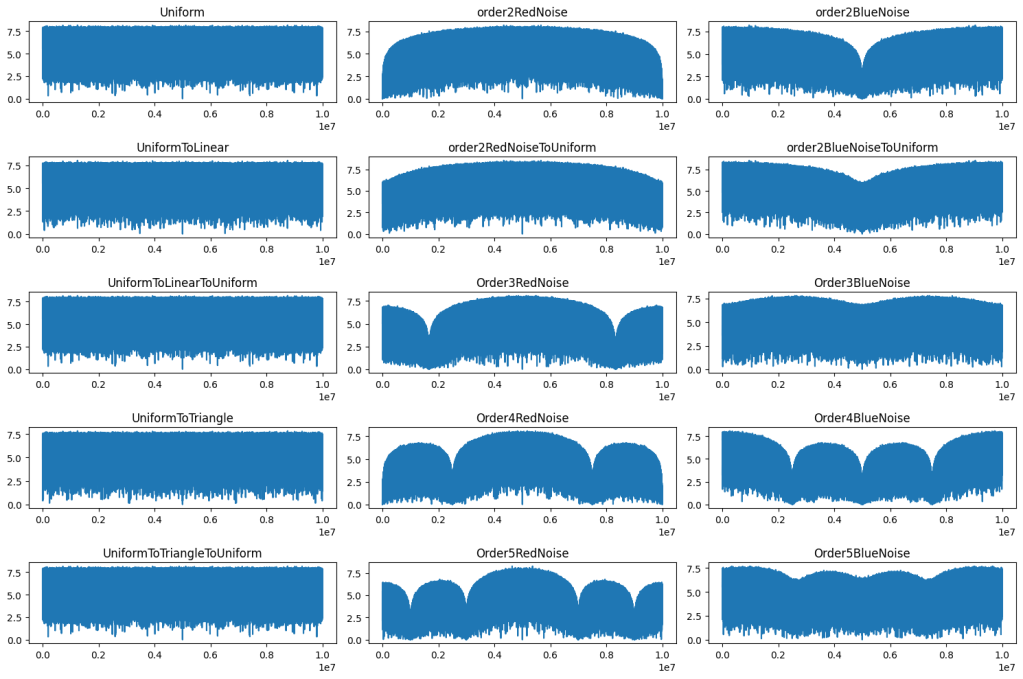

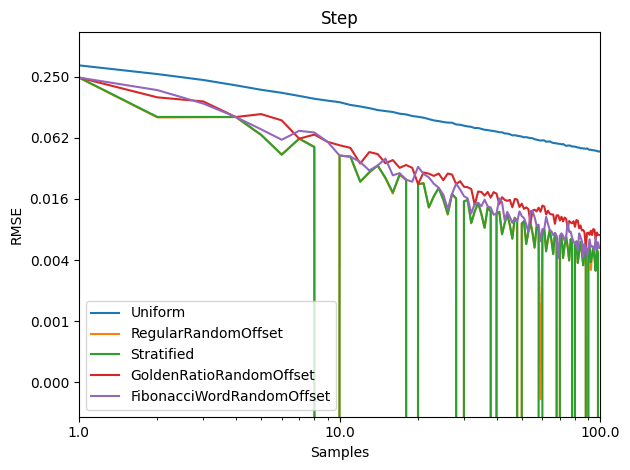

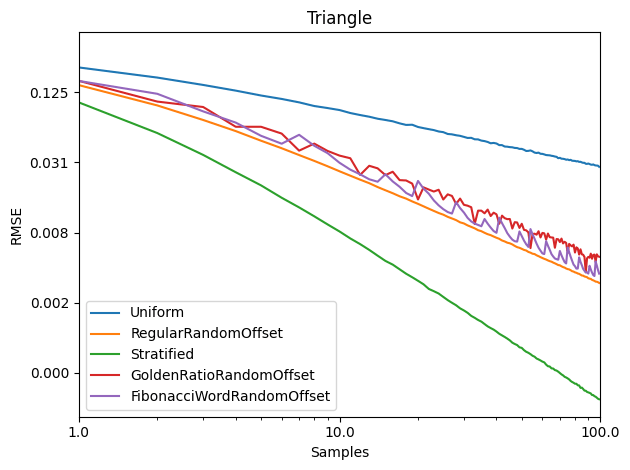

Results In Graph Quality Tests

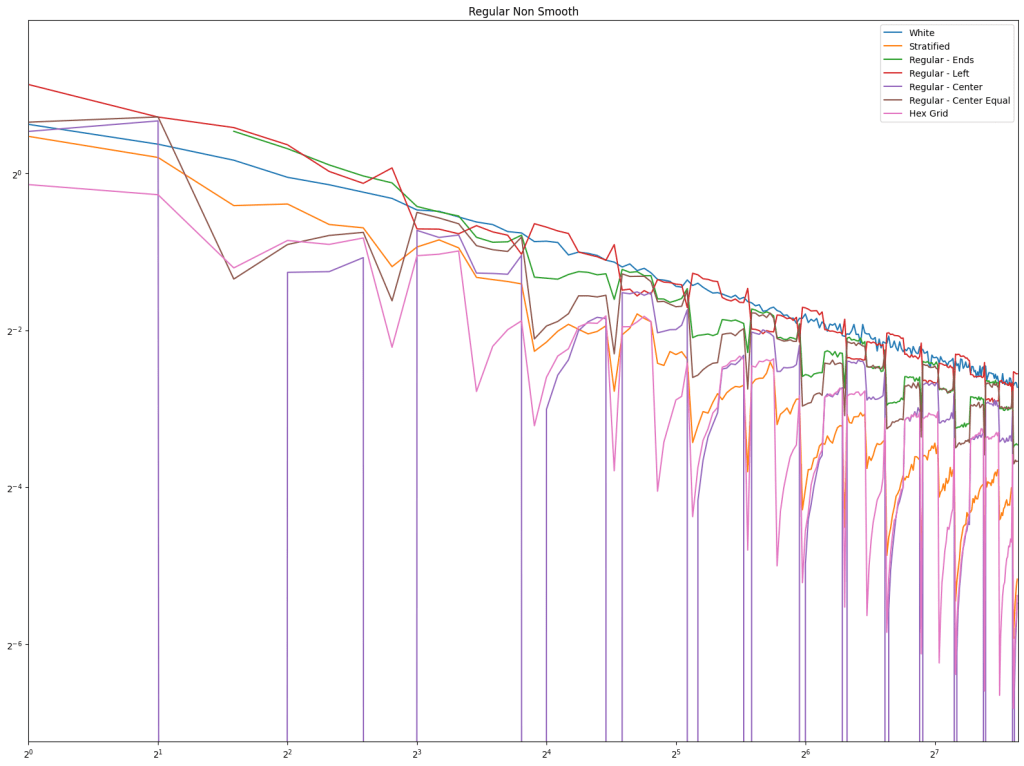

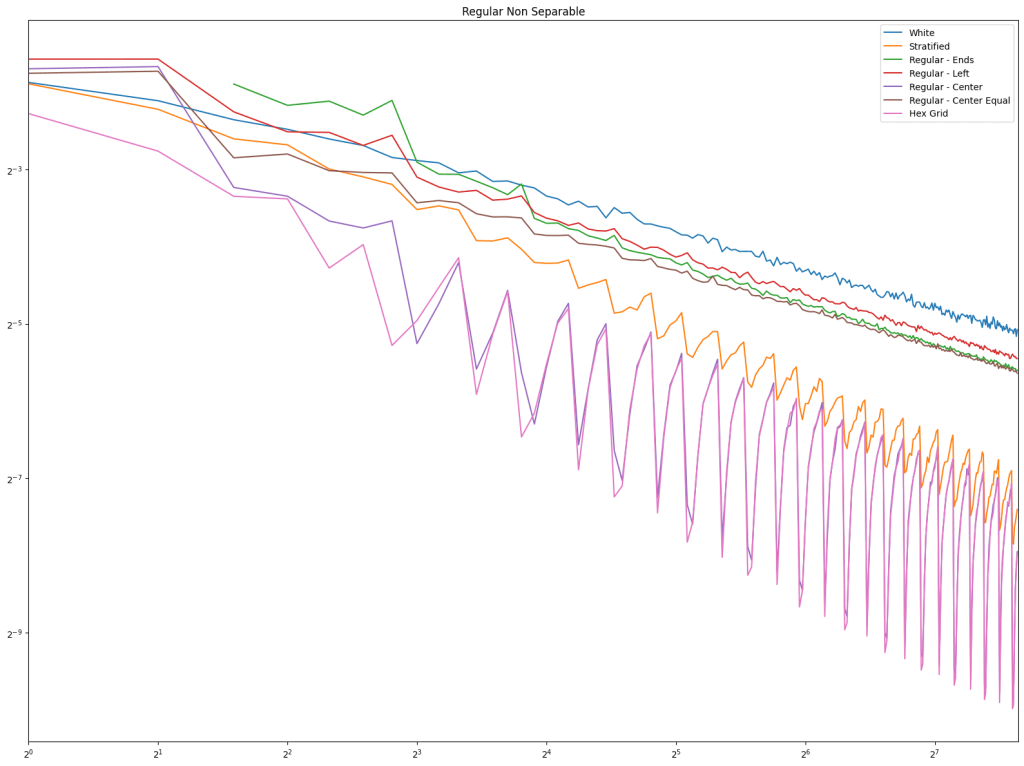

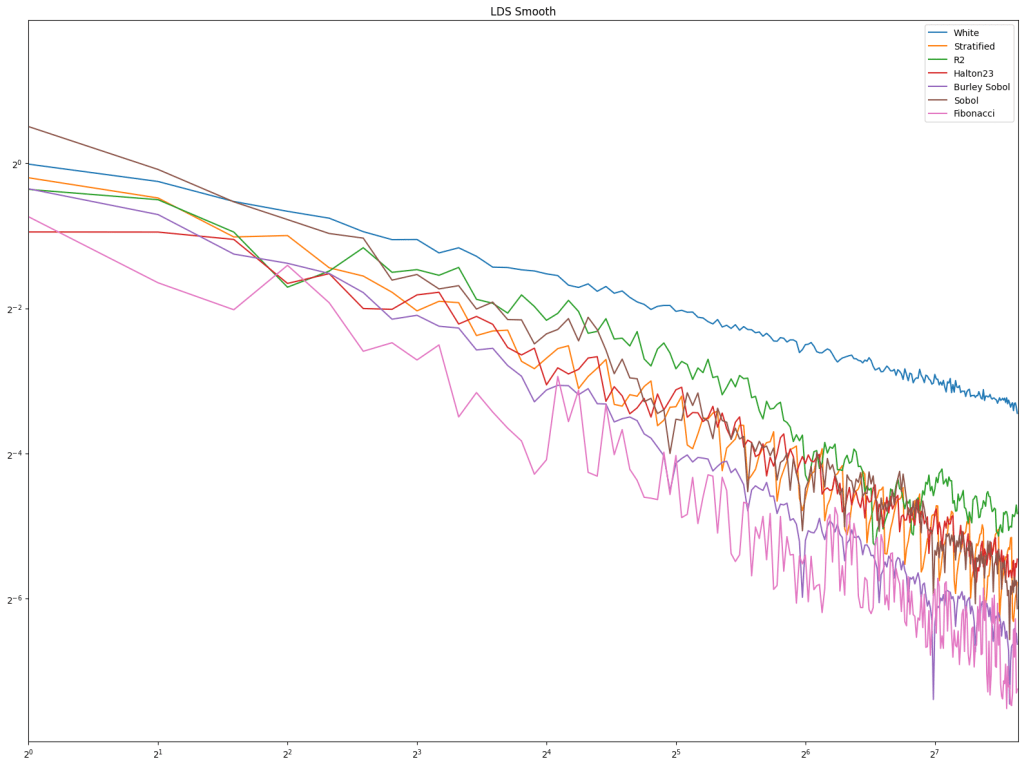

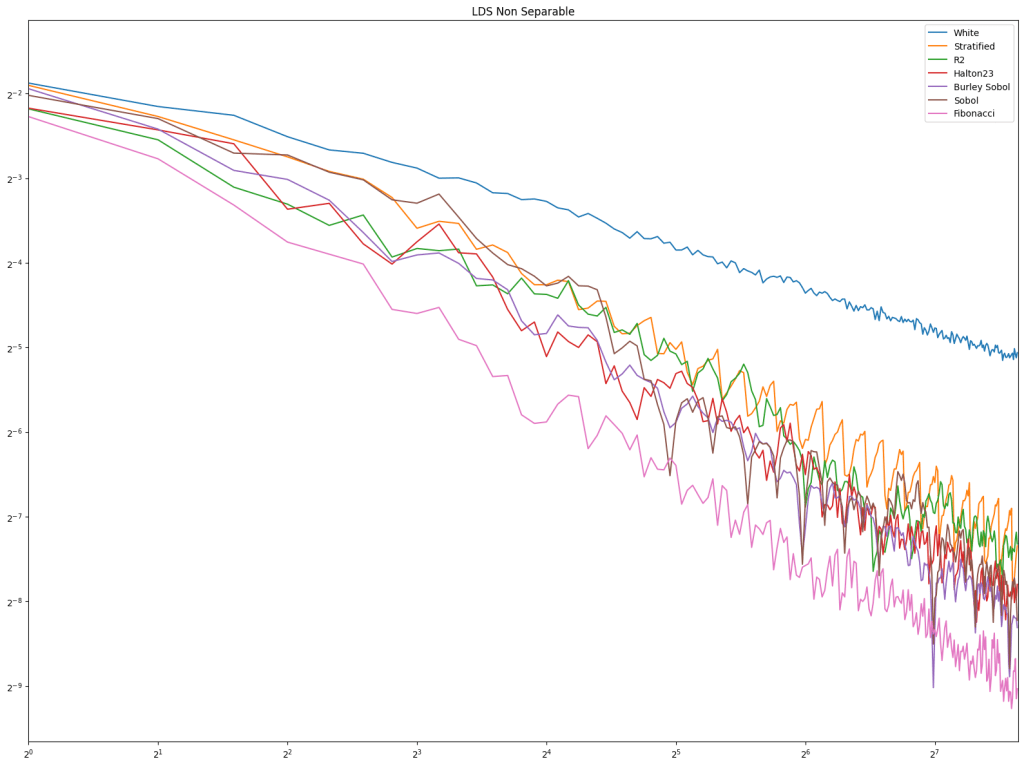

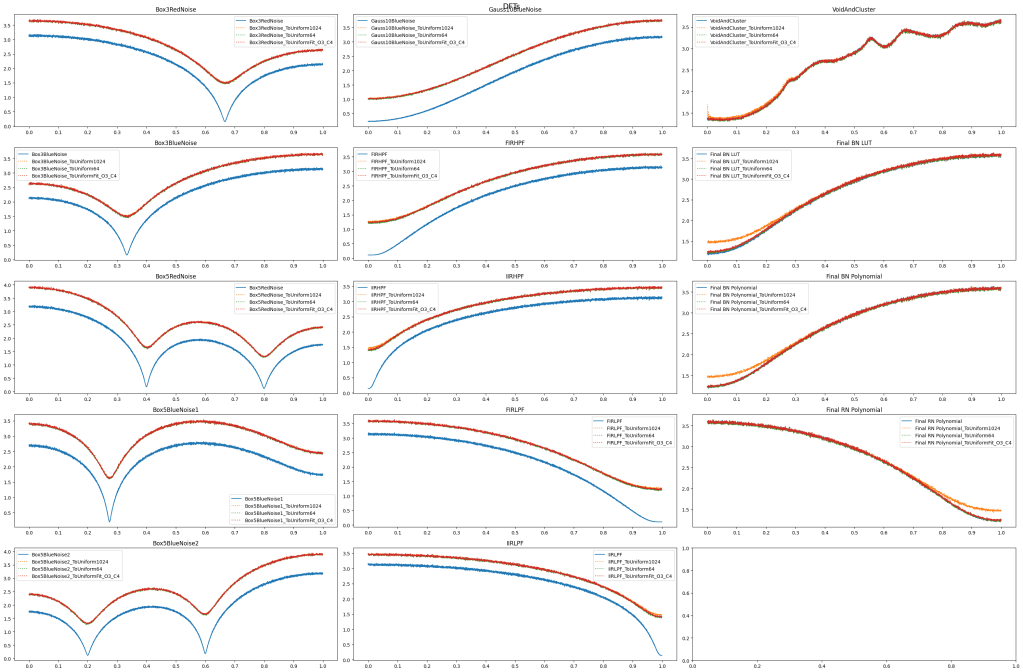

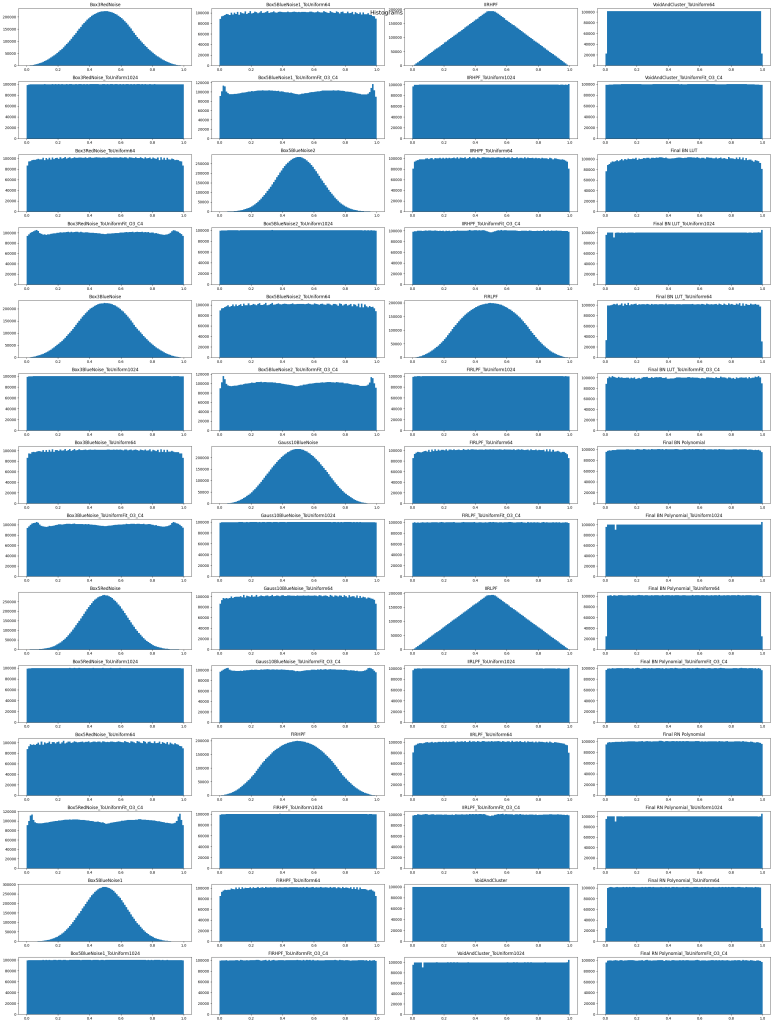

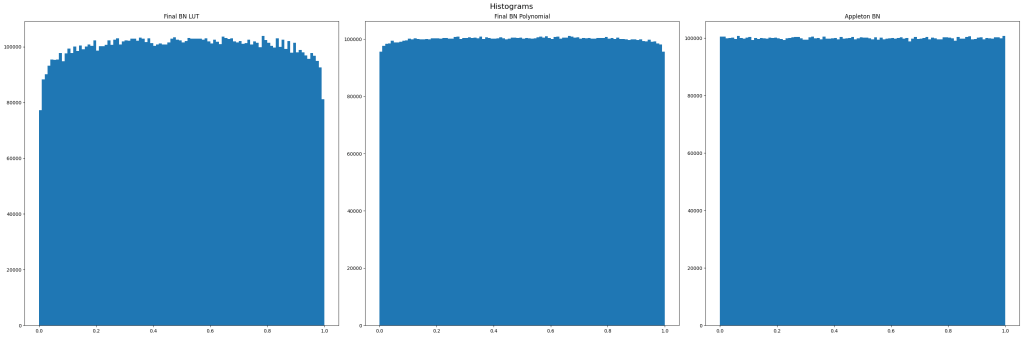

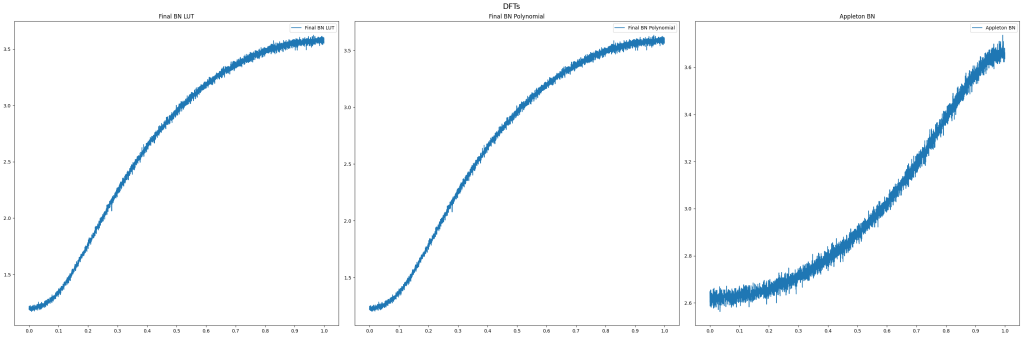

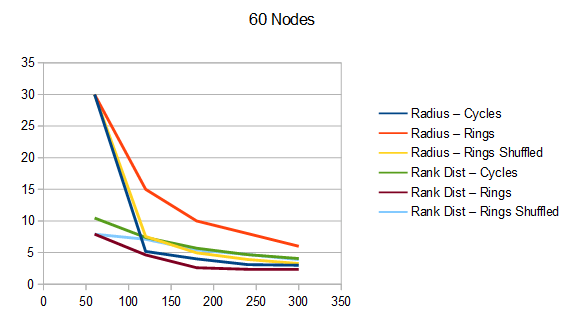

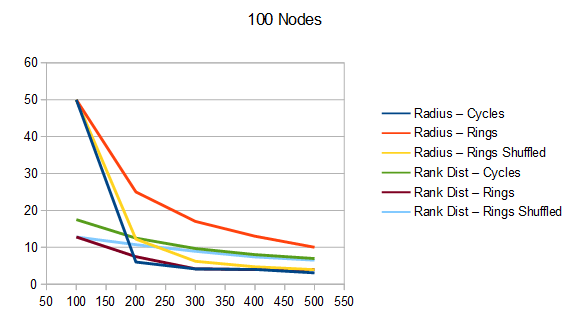

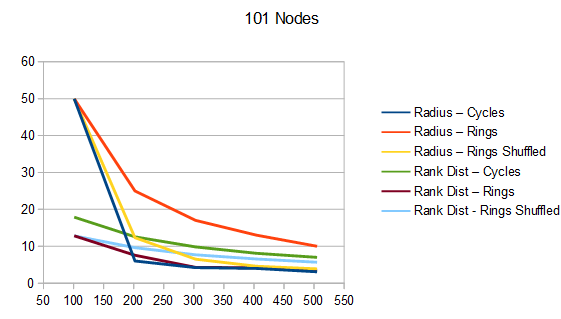

To understand the quality of these Hamiltonian cycles, I plugged them into the voting algorithm from the last blog post. I put in a version that does cycles in order (1, 2, 3 and so on), and also put in a version that does the cycles in a random order, but makes sure the first cycle is always 1, to ensure the graph is connected, in case the number of nodes is not prime.

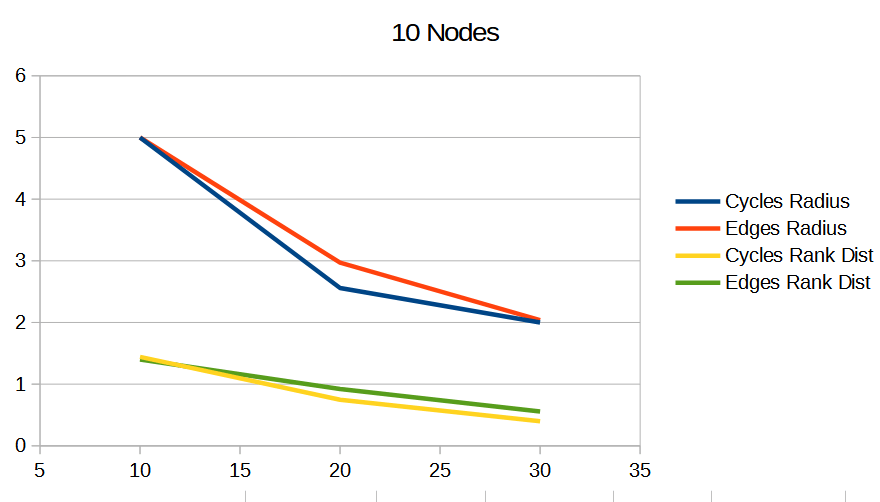

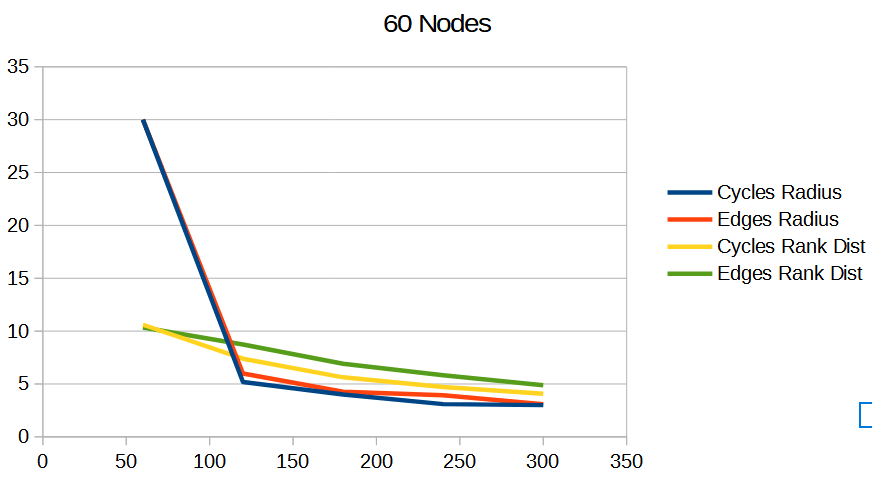

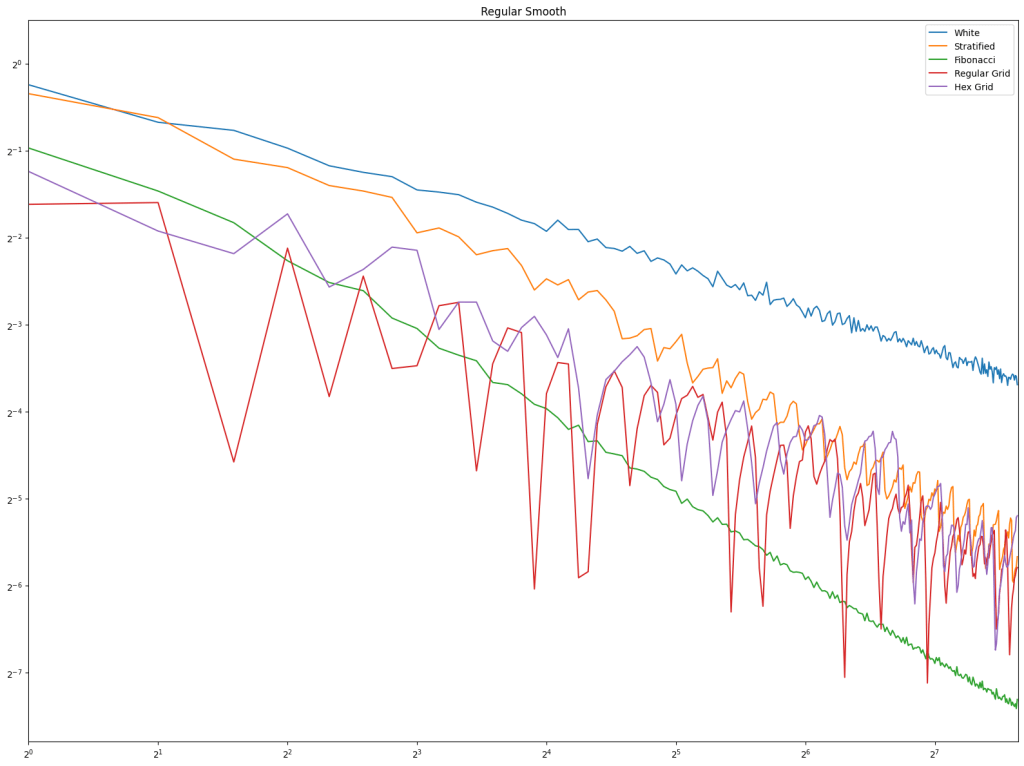

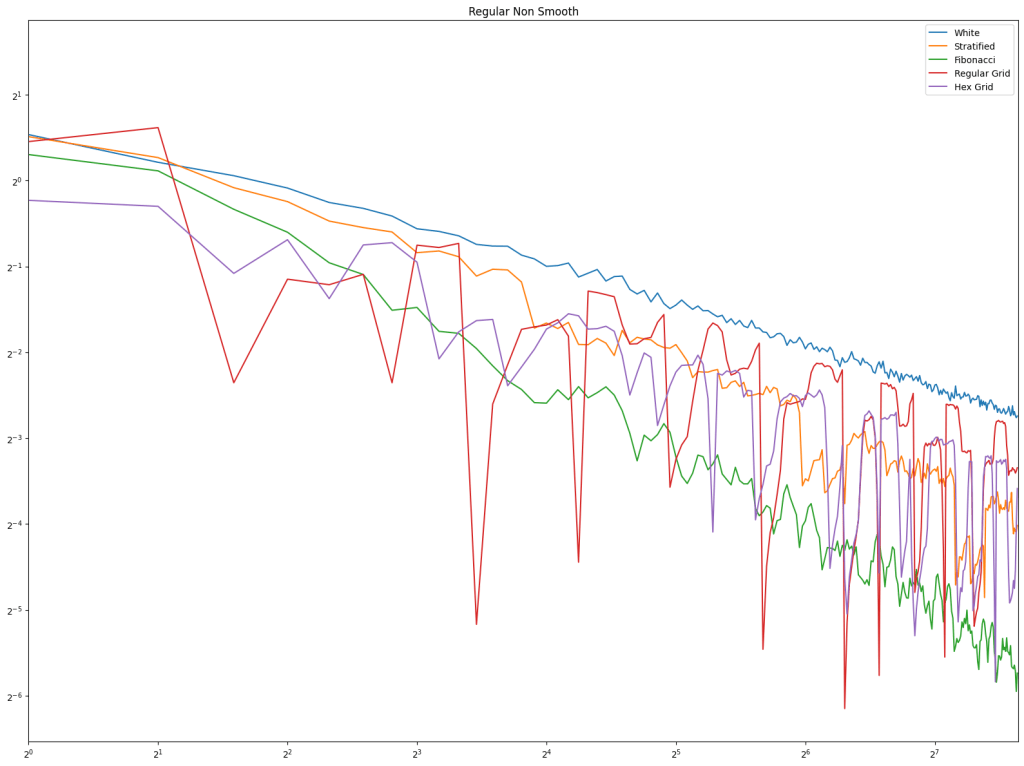

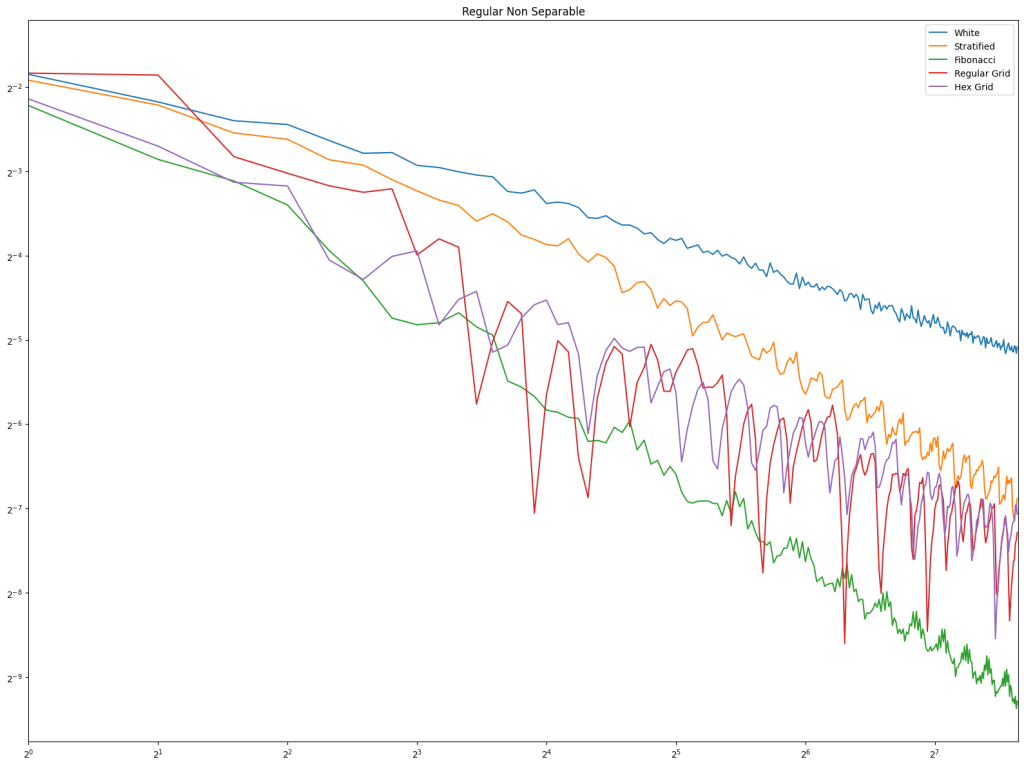

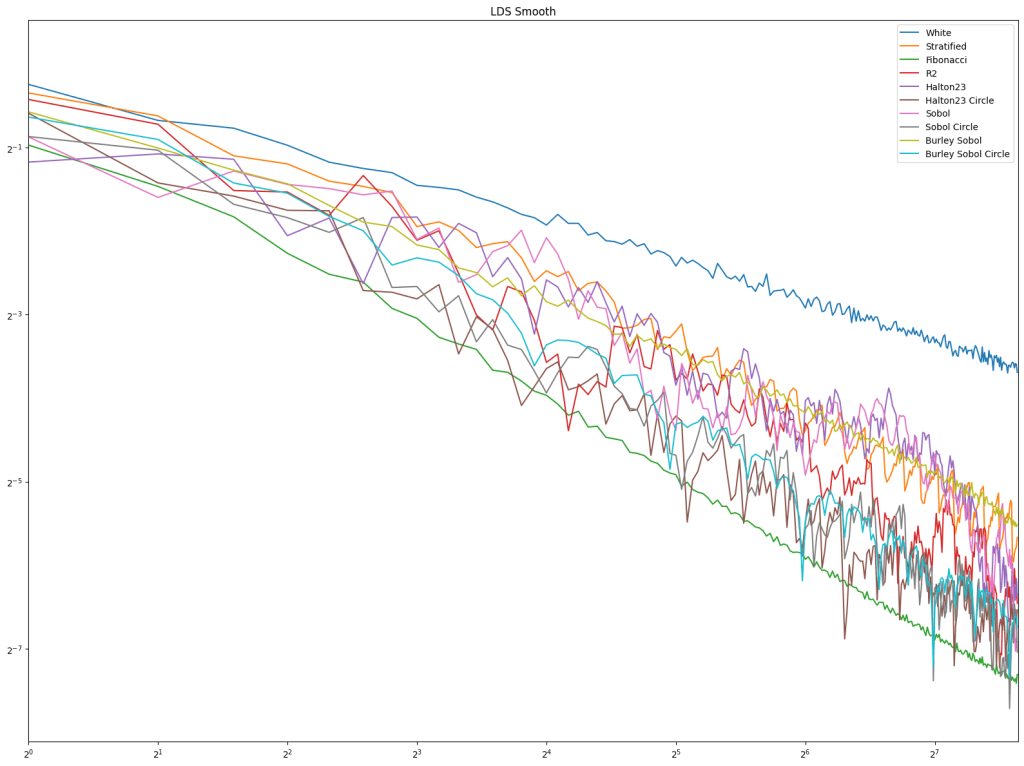

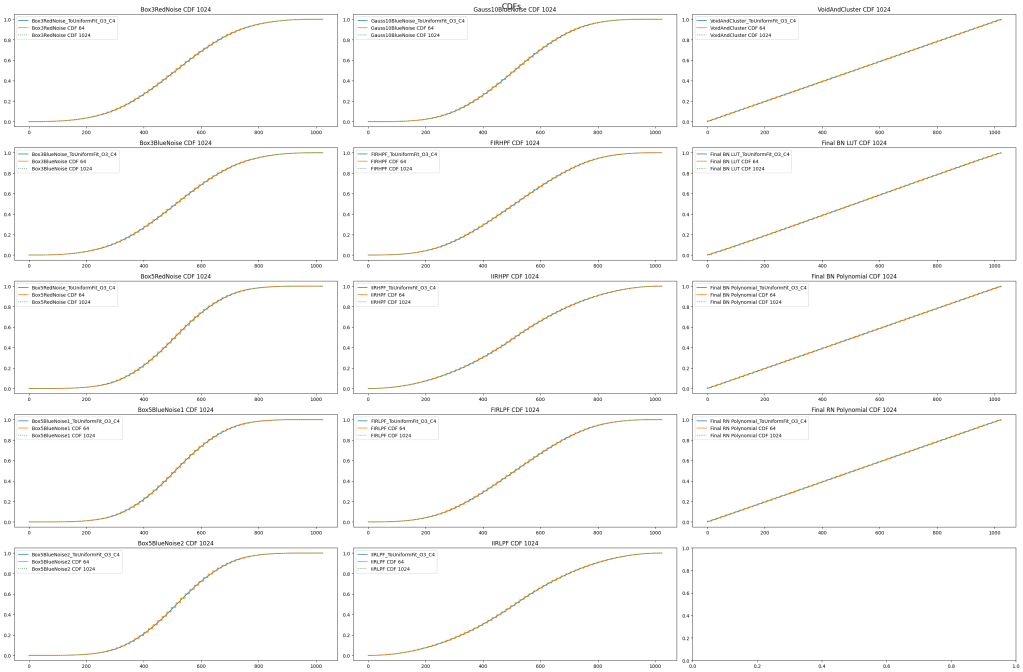

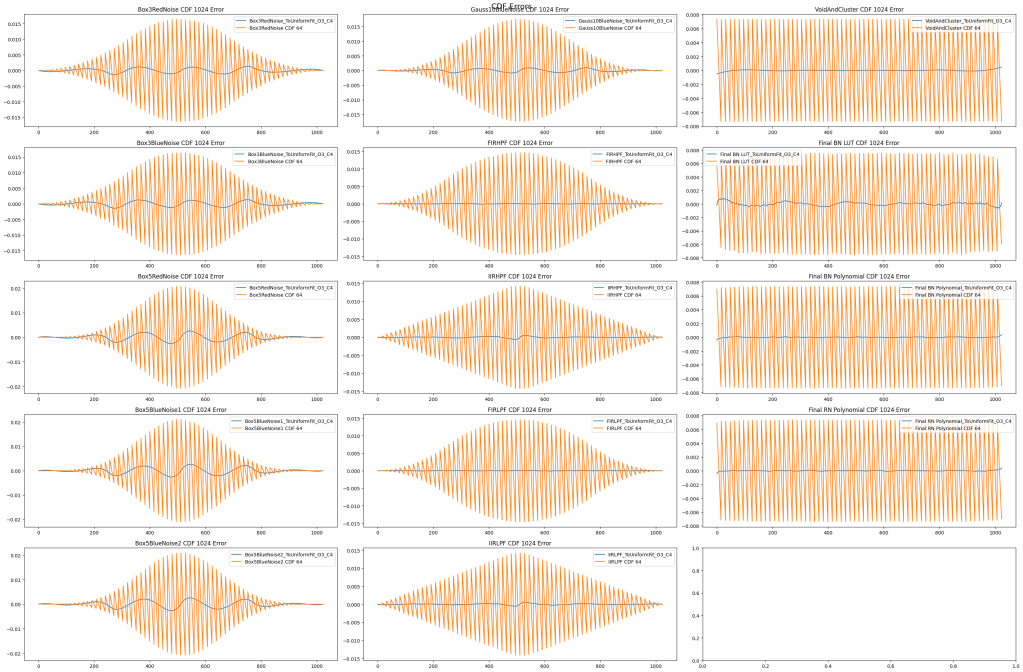

The graphs below are the average of 100 tests. The source code generates csv files with more information, including standard deviation.

For radius, cycles are randomly generated and rings shuffled are shuffled differently each run. The non shuffled rings are the same each test. For rank distance, the actual score value of each node changes each test, so all rank distance graphs are subject to randomization in each test. This can also be seen as shuffling the nodes before running the algorithm, which is sometime I talked about in the last section.

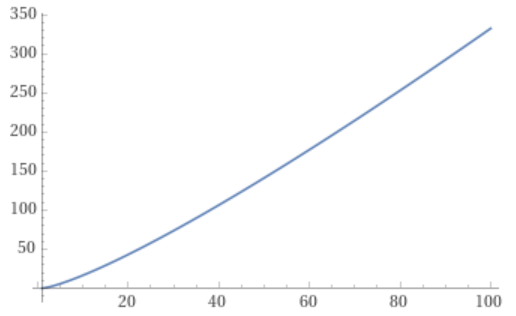

For both radius and rank distance, a lower score is better.

It looks like random cycles (the technique from the last post) decreases the radius the most. That is not surprising, since that is based on solid mathematics to reduce the radius quickly. Using the deterministic cycles in this post, but shuffling the order the cycles looks to be a pretty good method for reducing radius too. It isn’t as good as random cycles, but it can quickly and easily find as many non overlapping Hamiltonian cycles as you want, up to the full limit of how many cycles are possible. Randomly generating cycles until they are valid gets very slow for high cycle counts and high node counts.

These graphs tell a different story for the rank distance. These show that the NON SHUFFLED ordering of deterministic cycles do the best for making the most accurate ranked list. I’m a bit surprised, as this shows that decreasing radius may be a good idea for improving the ranked list quality, but it isn’t the whole story for making the highest quality ranked list approximation.

Perhaps this has something to do with radius being measured as the worst outlier, while the rank distance is calculated as an average quality of all nodes.

Quick recap on rank distance: The rank distance is calculated by using the voting algorithm from last post to make a ranked list, and then summing up the difference of each node’s placement in that estimated ranking list, versus the nodes placement in the actual ranking list. It’s the optimal transport cost to change the estimated ranking list into the actual ranking list. That value is divided by the number of nodes to try and normalize it.

Anyhow, thanks for reading and thanks to this video by CQFD for nerd sniping me with graph theory 🙂

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSDBbCaO-kc